Editor’s note: The goal of our Our Hope in Recovery series is to shed light on various diseases, conditions and ailments, in an attempt to help others who are struggling.

I was 27 years old and halfway through my master’s degree when I could no longer ignore how terrible I felt. I would come home from the end of a day of teaching and taking classes and collapse on the couch, waking up around 9 p.m. to have a few bites of dinner and then go back to sleep. I had gained weight — around 70 pounds — and my periods were nearly non-existent. My mood alternated between anxiety and depression, and I had recently discovered the beginning of a mustache spreading across my upper lip. These symptoms and many others had come and gone since I was 11 years old. I had been to doctors time and again with no real answers other than weight loss and exercise. Given that I had been on a diet of one kind or another since my mother discovered Richard Simmons’ Deal-a-Meal plan in the 1980s, I was pretty sure that more dietary restrictions weren’t going to cure me of whatever made my head hair thin and brown patches appear under my arms.

These symptoms and many others had come and gone since I was 11 years old. I had been to doctors time and again with no real answers other than weight loss and exercise. Given that I had been on a diet of one kind or another since my mother discovered Richard Simmons’ Deal-a-Meal plan in the 1980s, I was pretty sure that more dietary restrictions weren’t going to cure me of whatever made my head hair thin and brown patches appear under my arms.

By the time of my engagement, shortly after my 27th birthday, I had had enough of it all. I went to the doctor at the university health center and told him everything I was experiencing. He sat back in his chair and said, “Honey, it’s like this: each month your grass grows, but your grass just isn’t getting mowed.”

I stared at him in confusion until he took out his prescription pad, flipped it over and drew a picture of the women’s reproductive system. He explained with lines and arrows how periods worked. I sat next to him, raging inside as I watched his pencil etch fallopian tubes and what I guessed was a uterus, and wanted to rip it out of his hands and throw it across the room.

Finally, he said, “The thing is, you are not having your period regularly because you spend too much time sitting on your ass eating chips when you should be eating salads and running on a treadmill.”

I stifled my cries, not daring to give him the satisfaction of knowing how deeply his words cut me, and took the prescription for birth control pills he handed me. I gingerly stood up from the chair and carefully walked out the door of his office, fearing that if I moved too quickly, I would stumble and fall. When I finally reached the stone pathway that led back to my classroom building, I let out a shriek of anguish and despair.

I had been asking for help for these problems for 16 years and always ended up with the same diagnosis: “You are fat.”

But I knew that there was so much more to it than that.

When I got home, my fiance held me in his arms and told me that we would find a way to get me well, but I knew that if I was ever going to learn what was making me so ill that I would have to take that path alone.

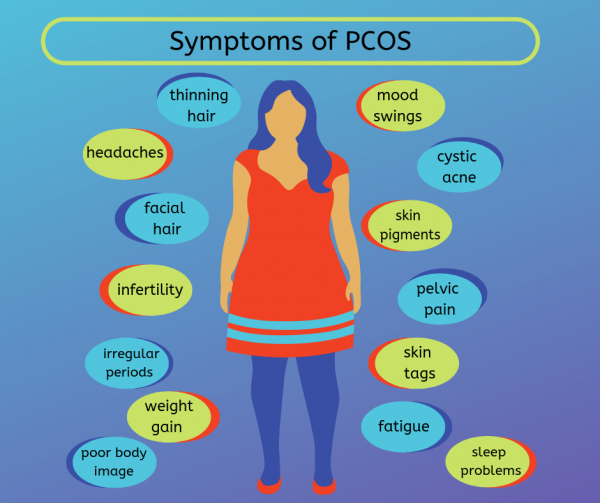

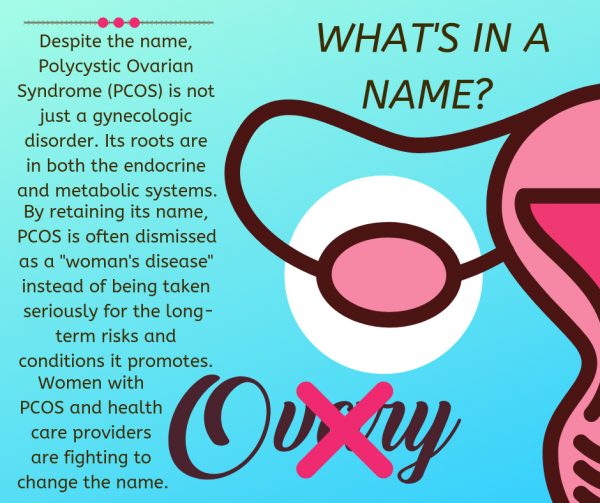

A few months later, I was searching the internet for my symptoms, and kept finding polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is a metabolic-endocrine syndrome that causes infertility, rapid weight gain, erratic menstrual cycles, cystic acne, brown patches of skin on the neck, armpits and inner thighs, male-pattern baldness, facial hair growth, mood disorders and other symptoms.

The more I read about it, the more I was convinced that PCOS was my tormentor.

THE QUEST FOR ANSWERS

One night around 3 a.m., I found a website on which a doctor from Costa Rica said that he would listen to women who felt like they had no support from the medical community. I emailed him my symptoms, and the next morning, he told me he was fairly certain that I have PCOS. I cried when I read his words. In so many ways, I was relieved to know that all I had been going through since shortly after my first period was because of this syndrome. On the other hand, I was sad to learn that my chances of conceiving were incredibly limited, and the odds that I would be able to ever maintain a healthy body weight were equally challenging.

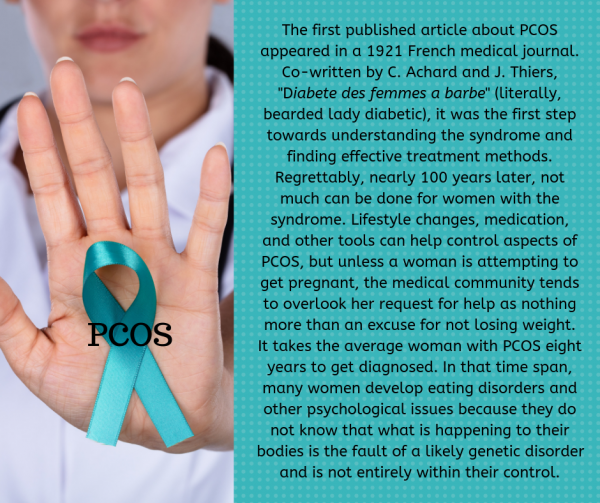

And this set off a nearly 20-year quest for wellness that was stymied by poverty, an eating disorder, lack of access to adequate medical professionals and treatments, and so much more. Thanks to the ever-expanding internet, I discovered hundreds of other women just like me who were struggling to find treatment and understanding from a world that could only see us as fat, lazy women who caused our own ailments and misery.

I joined hands with those women (we often call ourselves cysters) to fight for more medical studies and trials so that we can get the treatment we need not just to get pregnant, but to be healthy. Women with PCOS are at greater risk of developing high cholesterol, heart disease, endometrial cancer and other serious illnesses.

My first line of treatment was a drug called Glucophage (metformin), which is generally used to treat type 2 diabetics. Given that PCOS is primarily driven by the body’s inability to use insulin well (insulin resistance), metformin aids in improving symptoms of the syndrome by encouraging better insulin uptake. I saw improvements while on the drug, including weight loss, more stable moods, less facial hair and thicker head hair, but I was still struggling to conceive.

After a series of miscarriages, I finally got pregnant at the end of 2000 while finishing my doctoral coursework. The pregnancy began abnormal with frequent spotting and cramping, but my obstetrician kept assuring me that everything was fine. And then on March 4 at around 11 p.m., I began to bleed heavily. My husband rushed me to the hospital where we learned that the placenta had abrupted and the baby was coming. I was 28 weeks pregnant.

After an emergency C-section, our son Nicholas was rushed to Columbus Children’s Hospital by helicopter, where he survived on extensive life support for seven days before we decided to let him go. My dreams of motherhood were crushed, and I went home with empty arms and a broken heart.

Two weeks later, I took my comprehensive exams for my doctorate and left town for a PCOS conference in Atlantic City. There, I met other women just like me. We suffered the same. We struggled the same. But we also fought the same: hard. In that space, I learned that I was not alone and that there were doctors and other clinicians working hard at finding treatments for PCOS.

Although we began trying again as soon as my body was medically sound, miscarriages ended two other pregnancies. Not long after, our house burned down. In 2008 after being together for over 11 years, we divorced.

TRY, TRY AGAIN

In the years after my marriage ended, I worked even harder to control the symptoms of PCOS through low-carb diets, exercise, supplements, medication, and what seemed like an endless array of procedures and efforts. I remarried in 2009. He knew I had trouble conceiving, but we faced it together — at first.

Eventually, the pressure of infertility treatments, timing, doctor appointments and monthly disappointments began straining our marriage. I decided to take one last shot by having my left fallopian tube surgically removed. It has become diseased after an ectopic pregnancy, and its removal would lead to better chances of conceiving. Four months later, I learned I was pregnant. After spotting during the first trimester, the rest of the pregnancy was uncomplicated. At 40 weeks and five days, I gave birth to an 8-pound, 5-ounce baby boy we named Tristan. I was 37 years old.

In the seven years since, I have had regular ovulatory periods, but some of my other symptoms have worsened, such as my weight. While my head hair has thickened, the hair on my face has continued to grow more plentiful and require more maintenance. Although I never really suffered with cystic acne the way so many cysters do, I struggle with anxiety and depression.

I have tried just about everything available to women with PCOS: herbs, drugs, massages, surgery, diet, exercise, and on and on and find myself still dealing with this incredible burden that more people now know about, but many others still blame on the women who have it. It is our fault that we have this syndrome, we are told. If only we lost weight. If only we exercised. Most of us discover that with incredibly hard work, we can lower our weight, but that doesn’t mean our symptoms are better.

PCOS is a syndrome. It has no cure. The symptoms can be treated, but the root cause cannot be eliminated at this point. The best any woman can do is suppress the syndrome, but there are times when even her very best efforts are no match for a disorder that was first diagnosed in 1921 but existed long before then.

In a culture that is obsessed with thinness and self-mastery, women with PCOS are seen as unruly and impossibly out of control. We take up space in a world that would prefer women to be invisible.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT PCOS

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Department of Women’s Health, PCOS affects one in 10 women. Most women are diagnosed with PCOS in their 20s and 30s as a result of struggling to conceive. PCOS is one of the most common causes of infertility and miscarriage, but treatments are available to increase the likelihood of a healthy pregnancy.

The National Institutes of Health provides diagnostic criteria for PCOS, which is often referred to as a diagnosis of exclusion. That is, after all other health problems are ruled out, like pituitary tumors, high prolactin levels and thyroid disease, doctors then look for the following criteria to make a final assessment:

• Family history of PCOS, infertility or menstrual irregularities

• Complete a physical examination for acne, facial hair growth, skin tags, browning skin patches, waist-to-hip ratio and thinning head hair

• Order blood tests for male hormones, insulin levels and ratios of ovulatory hormones.

• Internal ultrasound to assess the condition of the ovaries. Some women with PCOS have what appears to be a chain of pearls on their ovaries, but not all women with PCOS will have these ovarian cysts.

Treatments vary considerably based on the health professional consulted, which can include a general practitioner, obstetrician, gynecologist, endocrinologist and others. The PCOS Center at the University of Pennsylvania recommends a number of treatments that apply to most women with PCOS, including weight loss and other lifestyle changes, the use of metformin or other drugs that improve insulin uptake, regular visits to a dermatologist for a reduction in acne and other skin issues, and treatment for head hair loss. For women who are trying to conceive, there are several routes to take, such as ovulation-inducing drugs, intermittent trials of birth control and other conservative approaches.

As I lurch towards menopause, I am not sure what awaits me. PCOS doesn’t disappear with the last menstrual cycle. Cysters in their 50s and beyond struggle with weight issues and many of the other PCOS-related problems they experienced earlier in their lives. I do know that for all the grief it has caused in my life, PCOS has given me a valuable toolset I use to advocate for myself and others. I knew for years that something was wrong with my body, I just didn’t know where to find the right answers.

• Christina Fisanick, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English at California University of Pennsylvania, where she teaches expository writing, creative non-fiction and digital storytelling. She is the author of more than 30 books, including her most recent memoir, “The Optimistic Food Addict: Recovering from Binge Eating Disorder.” She has been a Weelunk contributing writer since 2015. Christina is a 1996 graduate of West Liberty University and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She lives in Wheeling with her family.