Mabel Minns and her blind father, Tom, sat restlessly on a bench in the massive marble-floored waiting area of Wheeling’s B&O Station on a rainy evening in April 1944. Tom tapped his little bamboo cane agitatedly on the wooden arm of his bench and bounced the heel of his right foot off the floor in rhythm to a song that played in his head. He occasionally ran a hand nervously over

his bald scalp. Mabel picked fuzz balls off her sweater and shot glances at her tiny wristwatch at least twice a minute. The big station clock nearby moved its minute hands forward with two big loud clicks every 120 seconds.

The station was alive with frenetic activity. Porters wheeled carts full of luggage from train gates to buses and taxis waiting out on the street. Entire families stood excitedly in groups around the station waiting area in anxious anticipation of arrivals. A scratchy voice periodically came across the station’s loudspeaker to announce the arrival times of trains from Pittsburgh and Columbus. There was the unmistakable smell of burning coal in the air, even inside the massive depot.

Tom and Mabel had been waiting for the arrival of PFC George Griffith of the U.S. Army’s 201st Infantry, all the way from Alaska, for three solid grueling hours. Just 72 hours ago, the phone rang at the Minns’ little confectionary across from Center Market in the wee hours of the morning.

“Mabel,” a faint and distant male voice said. “It’s George. I’m in Seattle and on my way home. Make the arrangements. We are getting married on Saturday. Whatever you work out will be fine with me.”

After nearly three long years, the 201st, made up largely of West Virginians, including many Wheeling men, had been relieved of their harsh, bitter and dangerous duty in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. Every man was getting a two-week furlough before the unit would be reassigned. They had conducted lonely frozen beach patrols and performed backbreaking labor helping Navy Seabees build airstrips all while being frequently bombed and strafed by Japanese aircraft in bitter cold temperatures. They lost men to the violence of war, the ravages of disease, and mind-numbing boredom endured when days sometimes were without sun for 20 hours.

Now, George was due home, at least for a week or so, and the wedding originally planned for 1940 would finally occur. But first, this long wait had to be endured. A conversational distraction was needed. Tom’s bench was next to a wall, and he reached out with his left hand and felt the cool smooth marble of the grand old building.

“Mabel,” he finally said in his calming smooth voice. “Did you ever take a good look at this building? Look around now and tell me what you see.”

Mabel had spent her whole life describing things for her sightless parents so the request wasn’t that unusual.

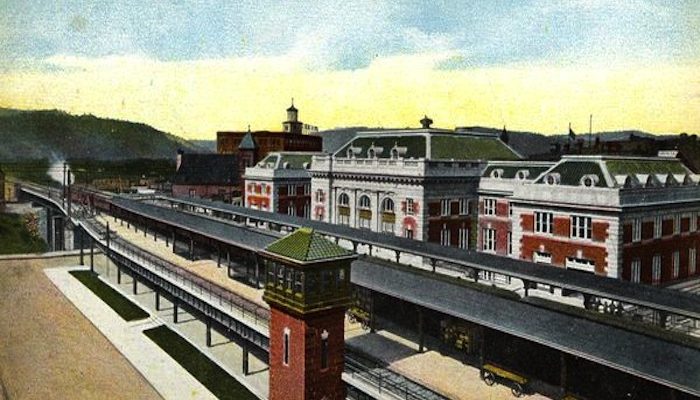

“Well Daddy, the outside is really impressive,” she began. “There are three main entrances, and the whole base of the building is granite. Each of the doorways are decorated with great big concrete things that look like knights’ shields. I think I had a teacher in high school who said they were called cartouches. Anyway, the initials on the shields say B&O. Then there are huge limestone columns on the second and third stories outside in the middle part of the building. It is brick outside except for the corners that have granite accents all the way from the bottom to the top.”

“What about inside where we are now,” Tom asked.

“We are in a very big waiting room that is two stories high,” Mabel answered. “The benches are all polished wood. There are huge black chain chandeliers, and the walls and floors are all marble. It really is a beautiful building.”

Tom interrupted.

“Way back when it was built in 1908, it was called ‘B&O’s magnificent present to Wheeling.’ It cost $300,000 way back then, so you can imagine what it would cost today. I have been told that the station design is French and is called Beaux-Arts. At the turn of the century, there were 100 passenger cars running in and out of the city every single day. That’s why they decided to build this fancy depot. This is a railroad town, Mabel. It always will be. More than 70 percent of all our manufactured goods go to market by railroad, not on the river as most people think.”

Tom, ever the avid historian, launched into a monologue about how the railroad came to Wheeling in 1852. It was his way of passing the time and diverting Mabel’s attention from the difficult wait. He explained how the mayor of Wheeling was authorized by city council in 1835 to buy 2,500 shares of B&O stock for $1 million on the condition that the city be named the western terminus of the

B&O. He told her that after years of financial and engineering struggles, the railroad was finally built across the mountains with the final rail laid in December 1852.

“My father told me about the day when the first passenger train arrived in Wheeling,” Tom said. “It was in January 1853. Thousands of people showed up. He said there was an extravagant dinner held for almost 1,000 people, and the Suspension Bridge, only 4 years old then, was illuminated with more than 1,000 lights. The railroad brought a real economic boom for the old town.

“In 1860, there were about 14,000 people living here but 20 years later, there were more than 30,000. You know, with the upturn in business for the steel plants and all the other factories around here, the railroads will keep us growing and strong for decades to come. This old building will be around a long time and bring people in and out of the Valley when your grandchildren are around.”

Tom wrapped up his lecture, and eventually the last trains of the day arrived at the Wheeling B&O station, and there was no George. Mabel leaned her head against her father’s shoulder and sobbed quietly. Tom put his arm around her and offered comfort.

“Something’s gone wrong someplace,” he said. “Let’s go home. Maybe he’s called, and your Mother has some news for us.”

They walked sadly and slowly back down Market Street to their little store and the upstairs apartment. Mabel was deep in thought about all that had to be done to undo the wedding plans that had already been set into motion and worried about where George could be.

She rethought George’s 4 a.m. call from Seattle 72 hours ago and then reviewed in her mind the whirlwind of activity that it touched off. She remembered that she didn’t go back to bed after the line went dead and they were cut off. Instead, she paced the floors of the apartment upstairs of the Minns’ store and waited until businesses opened. Then, she made a flurry of calls to the minister of Wesley Methodist Church on Jacob Street, to a photographer that a friend recommended, and to the couple who had agreed so many years ago to serve as best man and maid of honor—Bradford and Ruth Tye.

Brad, a native of New York City, was a mathematics teacher at Linsly Military Institute and would eventually finish his career as a respected mathematics professor and mentor at Bethany College. The Tyes and Mabel and George had all been in the Wesley Church choir in the pre-war days and had struck up a lifelong friendship.

Lizzie, Mabel’s mother, had volunteered to go on telephone duty and make calls inviting friends and family to the long-delayed and now last-minute ceremony. George and Mabel’s Sunday school teacher agreed to organize women to pool sugar ration coupons, bake cookies, and make punch for the wedding reception at the church.

Four hours after George’s call, Tom put on his Fedora, grabbed his cane and headed north for downtown on one of his mysterious missions. When he came back, he and Lizzie pulled Mabel aside and handed her an envelope. Inside were $65 and two bus tickets for Fairmont, W.Va.

“I’ve never been to Fairmont,” Tom said. “But I’ve always heard their hotel downtown was one of the finest in the whole state. Take these tickets and the money for your honeymoon. It’s not much, but your mother and I wanted to take care of the trip for you and George. This is one of the most important times of your life. and we couldn’t be happier for you and to have George joining our family.”

It was an $80 gift in 1944—about $1,100 in 2015

dollars. It was a staggering sum to the little family that spent decades scratching out a living by selling pop, candy, and cigarettes in a series of little stores, delivering newspapers, and selling Lizzie’s hand crafts and baked goods sometimes door-to-door.

Mabel cried at what she knew to be a gigantic sacrifice. Lizzie cried at the very thought of being without Mabel for the first time in 25 years. Tom dabbed his own tear with a handkerchief and changed the subject to talk about the war in Europe.

Now, two days later, after their long wait and sad walk back home, it looked as if all that work and preparation was only a prelude to disappointment.

The bell over the little store’s front door gave out its usual jingle when Tom opened the door with Mabel following closely behind. She later told of entering the big dining room/living room area just behind the store with her eyes cast down at the floor in despair. She saw the shoes first. They were black lace-up shoes, and her eyes followed them to sharply creased khaki pants. She looked up all the way up and into the face of the weary Army private who held out his arms with tears in his eyes but a beaming smile on his face. George was home. They embraced for the first time in three years.

“We’ve been at the station all afternoon,” Mabel sobbed. “We thought you weren’t coming.”

“We had to take another train out of Columbus,” George managed to say with a breaking voice. “It took us into Weirton, and we had to take a bus down Route 2 but it got me here faster, and I walked over here but you were gone. I’m home!…I’m home!”

George then hugged his short happy future father-in-law so tightly that Tom lost his grip on the little bamboo cane. Lizzie, through tears of joy, set the table for a celebratory meal of meat and potatoes.

The wedding went smoothly. George was humbled by the size of the crowd that pressed into Wesley Methodist Church. Lizzie’s parents were there from Buckhannon and her youngest sister, Mary (the family called her “Pete”), who worked in a Columbus factory making war munitions, made it just in time. Mabel’s namesake, Aunt Mabel Murphy and her husband, Raymond were there. and so was Lizzie’s third sister, Ica (pronounced Ice), and her husband, Earl. Her brothers, Paul and Jake, also made it along with their wives, Ida and Gladys. Their attendance was a minor miracle considering the short notice and gas rationing.

Although many of them were away at war, there was still a good representation from the men and women who knew Mabel and George from loafing in Tom’s store over the years. There were cops and firemen in attendance who were Tom’s buddies and Mabel’s girlfriends from high school. Their old blind friend Chris Cerone played the organ but not the boogie woogie tunes for which he was famous.

Pictures were taken, cookies were eaten, rice was thrown, and a doctor friend of Tom’s gave the newlyweds a ride in his big black car to the Wheeling bus station. They boarded a big old “turtleback” bus for Fairmont where they enjoyed the luxury and fine food of the elegant Fairmont Hotel until heading back to Wheeling.

Too soon, George headed back to the Army, but this time to Fort Ord on Monterey Bay of the Pacific Ocean coast in California instead of the misery of cold Alaska. The Japanese had been forced out of the far reaches of North America, partly as a result of the work of the 201st. Fort Ord was considered one of the most attractive locations of any Army post because of its proximity to the beach and the weather. George’s luck had clearly changed. He remained in California training new recruits on the use of the Browning .30-caliber medium machine gun that he had mastered in Alaska. He remained the company barber and continued to send nearly all of his earnings home for saving. And, oddly, after spending three years doing hard work on a treeless frigid island in the dark, he endured his first bout of ill health.