Mabel Files 10—Tom’s Radio Part 1

“He’s coming Mama and he’s got it,” 13-year-old Mabel called out to her mother, Lizzie, on a Saturday morning in April 1932. Mabel had been gazing up the sidewalk of Jacob Street and spotted her father, Tom Minns, cruising toward their store/home at his usual speedy clip.

Tom tapped his bamboo cane on the brick sidewalk with his right hand and held a big package under his left arm. It was the day Tom Minns, came home with the most expensive single item he had ever purchased in his life—a bulky package wrapped in brown paper with the words “Earl Rogers” stamped clearly on the outside. The Minns family had scraped together enough money from various enterprises to buy their first radio. It was a major investment and a life-changing addition to any family during the Great Depression but it was a true blessing to a family headed by blind people.

Tom had carefully considered the radio he wanted. He needed something light that could accommodate the family’s frequent moves from place to place in South Wheeling that were usually instigated by the appeal of lower rents or better commercial locations. Most importantly, he needed a radio that he could easily move from storefront to living quarters so the family could use it after his confectionary closed every night.

After visiting several stores including Stone and Thomas, The Hub, and Cooey Bentz, he settled on a model he found at the Earl Rogers Furniture Store on Main Street called the Crosley Model 129 “Justice.” It had six tubes inside a wood veneer cabinet and it sold for $39.95—the equivalent of more than $600 today. It was quite a financial investment. Mabel and Lizzie had saved money by selling what they called “ice balls” on the sidewalks of South Wheeling. They were what we know today as snow cones. Lizzie would use a shaver that looked like a woodworker’s plane to scrape shavings from a 25-pound block of ice that was delivered to the store every morning to keep pop and milk cold in the cooler. Then she scooped the ice into little glass containers and poured a variety of homemade syrups over the ice. Mabel set up a little stand on the sidewalk in front of the store and sold them for 3 cents each every summer—for years. The proceeds went into a little Marsh Wheeling Stogie box until being deposited at the bank in their little “radio account.”

Meanwhile, Tom, ever the entrepreneur, had taken on another moneymaking endeavor. He started a door-to-door operation with the help of a neighborhood boy. Three times a week, he would gather a bundle of brooms, mops, dish towels and other items he bought at wholesale prices from a local supplier, load them up in the hand cart he built himself, and knock on doors from South Wheeling to North Wheeling. It took years, but Tom’s work and Lizzie’s flavored ice treats eventually made the radio fund big enough for the beginning of the radio era for the Minns family.

A crowd of young people had already gathered in the store that Saturday morning, which was unusual for that time of day. Radios were not exactly a novelty in 1932, but in South Wheeling, they were still somewhat rare. For the Minns, getting a radio was a high priority since the technology evened the information and entertainment playing field for sightless people.

Tom gently placed the package on the candy counter and pulled out his faithful penknife to cut the cord that held the brown paper around his precious acquisition. Mabel jumped up and down and clapped in anticipation.

“Calm down Mabel,” Lizzie commanded. “It’s just a machine.”

A teenager in the storeroom whistled approval when the brown paper wrapping was finally pulled away from the radio. Its polished veneer walnut wood seemed to gleam and reflect sunlight through the big confectionary window. Its little round control dials were strategically located under a tiny tuner window and seemed to accentuate the “cathedral” shape of the contraption. The speaker on the front was cloth covered and shaped like a leaf of some kind.

Tom picked the radio up with both hands and walked over to the shelf next to the doorway that led to the family’s living quarters. This was to be the radio’s daytime home and the spot had been carefully cleared, cleaned and prepped for this moment. Tom placed it down gingerly and took the cord in his hand. He plugged the radio in and then reached for the knob.

“Which one is it Mabel,” he asked. “Don’t turn it on. Just tell me.”

Mabel took a quick look at the configuration of the knobs.

“The knob on the right turns it on, Daddy,” she said. “The one on the left changes the stations.”

Tom reached for the knob on the right, and, when his thumb and index finger had a firm hold, he twisted gently until everyone heard the distinctive “CLICK.” He twisted more to increase volume. Nothing happened. Mabel groaned.

“Just wait a second or so for the tubes to warm up, Mr. Minns,” offered a boy in the group who seemed to have some experience.

“Then, after you hear some pops and hums, you have to turn the other knob to find a station, Mr. Minns,” offered another boy in the group.

Tom listened for the “pop and hum” and when he heard it, he found the knob to the left and began a slow twist.

The first words out of the radio that would eventually bring them FDRs “fireside chats,” and hours of music and comedy, alert them to natural disasters, and explain in frightening detail the attack on Pearl Harbor, the blitz on London, and the desperate battles of a world war was a commercial for Barbasol Shaving Cream.

“Barbasol, Barbasol…No brush, no lather, no rub-in…Wet your razor then begin,” sang the quirky high-pitched male voice of “Singin’ Sam the Barbasol Man.”

The reaction in the store was loud and spontaneous. There were giggles, laughter, cheers and claps of the sort that would someday soon be the standard reactions to Jack Benny one-liners or Charley McCarthy wisecracks.

When the Barbasol pitch concluded, a smooth baritone voice came through the speakers.

“Welcome back ladies and gentlemen to the A&P Gypsies Show with Harry Horlik and featuring the Ipana Troubadors, the Clicquot Club Eskimos, the Happiness Boys, Scrappy Lambert, and the Silvertown Cord Orchestra with the Silver Masked Tenor brought to you by A&P stores.”

“Ipana2” by http://www.nfo.net/usa/h6.html. Via Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ipana2.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Ipana2.jpg

When the Goodrich Zippers—a banjo driven orchestra—began an up tempo tune, the kids in the store broke out into dance, and smiles emerged on the faces of Tom, Lizzie, and Mabel. It was a great beginning for radio in the Minns household.

The Great Depression deepened, and Tom, fearing the worst for the immediate financial future, began to question the wisdom of his radio investment. As money became scarce, the number of people spending money in the confectionary began to fall off. But, between Chris Cerone’s piano playing and the music shows on the radio, spirits remained relatively high in Tom’s store. He followed the news closely and heard stories about bank runs, plant closings, and increasing bread lines. Outwardly unshakable, Tom couldn’t help but be just as frightened as most adult Americans who followed the situation with great interest.

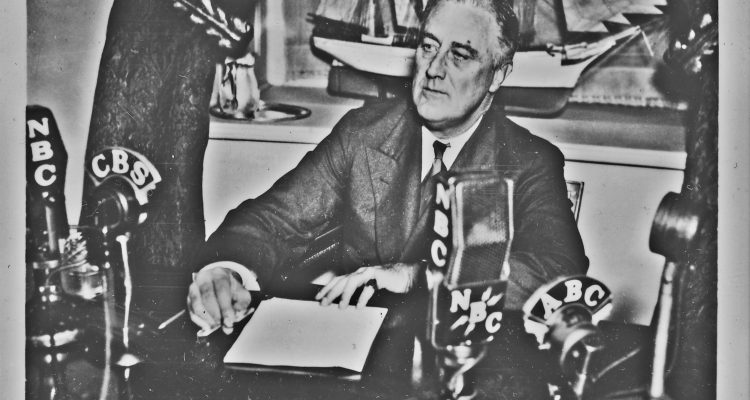

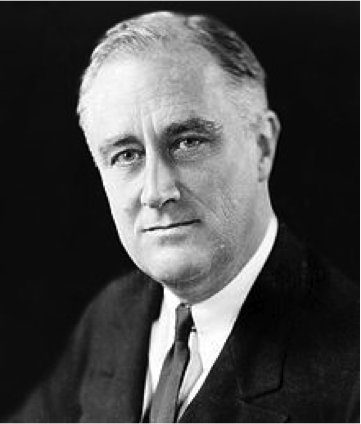

On March 12, 1933, Tom’s radio brought confidence and a greater understanding of the nation’s plight. That night, Tom told the loafers that there would be no music or hilarity and that they would, instead, all listen to President Roosevelt’s radio speech – the first of what became known as FDR’s Fireside Chats. By the time Roosevelt took office in 1933, nearly all the banks had closed at least temporarily in response to bank runs in which people made mass withdrawals in panic.

Tom kept the store open later that night so as many folks as possible could cram into the little room to hear the President. As Tom turned on his Crosley, people took seats atop the pop cooler and leaned against the bread counter. Others sat cross-legged on the wooden floor. Through the static, a calm and forceful voice with a distinctly New York accent began to address the nation.

“I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking—with the comparatively few who understand the mechanics of banking but more particularly with the overwhelming majority who use banks for the making of deposits and the drawing of checks,” President Roosevelt began. “I want to tell you what has been done in the last few days, why it was done, and what the next steps are going to be.” (Read the whole speech and access an audio recording of the speech that the Minns family and the store customers listed to here.)

It was the first of many times when Tom felt better after hearing Roosevelt speak. There would be 29 more “Fireside Chats” through 1944, and for each and every one, Tom stayed open late and made his customers sit and listen. Often, vigorous discussion followed and so did sale of pop, candy, and cigarettes.

Tom’s Crosley continued to fill the role of entertainer, educator, and news source throughout the Great Depression, lifting hopes, providing laughter and promoting understanding of crisis.

Having received extensive music appreciation training, as well as lessons on the violin and organ, Lizzie took particular pleasure in the radio’s offerings. She relished concerts by the New York Philharmonic and hushed her family’s happy chatter when her favorite composers’ work came through the static of the Crosley’s little speakers.

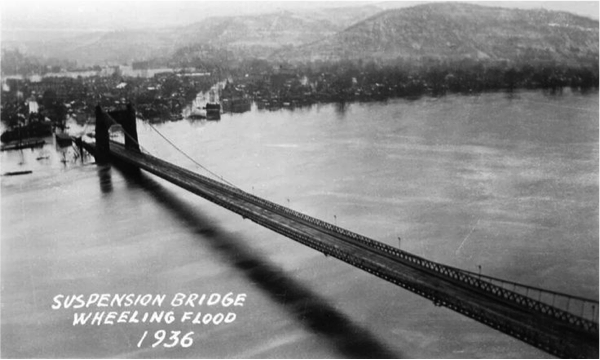

In March 1936, the hard-working little radio proved its worth when one of the worst floods in the city’s history engulfed the Depression-weary people of the Ohio Valley. The solemn announcers of WWVA began to advise residents of flood danger on March 16.

The Minns store was on Jacob Street, and an elderly neighbor who had lived in the same house for many years assured Tom that he had never ever see the water reach his home. Tom, Lizzie, and Mabel were concerned for their neighbors and hunkered down for whatever happened. The radio stayed on bringing reports of the river stage to worried listeners.

At about 10 p.m. on March 17, Mabel ventured out to have a look around the neighborhood. She wished her beau, George, was with them through the crisis. He was back from his CCC enlistment, but he was busy helping his barber college prepare for the flood by moving equipment to the upper floors of his Wheeling headquarters.

“Daddy, it’s coming up Water Street fast,” she reported upon her return “I think it’s going to reach us.”

To humor Mabel, Tom moved a few basics to the family’s upstairs bedroom, but he didn’t really believe there was anything to worry about. He left the Crosley in the downstairs kitchen and directed the family to get some sleep.

The next morning, March 18, he headed straight for the spot where he usually kept the radio on the second floor so he could listen to the most recent reports. That’s when he realized that he had left it downstairs. He headed down the narrow wooden steps that led to the first-floor kitchen and got to within two steps of the bottom when his foot descended into two feet of water. Tom’s little dog, Pal, was yapping furiously.

Mabel looked out the second floor window to see water everywhere and neighbors hanging out of their second floor windows with looks of amazement, fear and confusion on their faces. Tom waded through the water to retrieve the Crosley and set it up on the second floor and turned it on to get the news. Then, he, Lizzie and Mabel formed a relay chain and began moving whatever they could salvage to the second floor. The radio played at top volume so they could keep up with the situation.

They heard reports about how the Ohio roared up Market Street and submerged it under water. Wheeling Police Lieutenant J.E. Stanley was interviewed on WWVA and reported that 10 people died trying to escape the rush of water, and an explosion in an inundated building killed four others.

At 2 p.m., the WWVA announcers reported that the river was still rising and was expected to crest at 55 feet by 8 p.m. – nearly 20 feet above flood stage. The serious voices that came out of Tom’s Crosley presented incredible stories of rescue, death, and survival.

The radio told them that more than 6,000 people were rescued from the raging waters. The Minns family learned about heroic rescue team efforts that saved men, women and children from the second floors of Wheeling buildings using more than 100 motorboats. They learned about the work of Colonel C.B. Hopkins and Frederick Libbey, who made more than 100 rescues in their 20-foot powerboat, fighting the rage of the river currents that ran through city streets.

“The heroic pair battled the tides and sometimes had to propel their boat by pulling themselves along on a trolley wire when their boat motor failed,” the announcer explained. “At other locations more than 20 children, sick with the measles, were lifted through a second-story window and into boats for transport to safety. “

Before the floodwaters receded, 17 Wheeling residents were dead, and nearly 20,000 people were temporarily homeless. WWVA Jamboree country music stars who were used to the Saturday night footlights of the Virginia and Rex Theaters pitched in to set up cots and welcome the homeless to shelters like the one established at the civic auditorium that once stood on land that is now Stones Plaza on Market Street.

Tom, Lizzie and Mabel were stunned by the announcer’s next proclamation.

“This just in to our studios: the Reese family of Buchannan, West Virginia (Lizzie’s parents) contacted us to inquire about the safety of the Minns family—a blind couple living in South Wheeling who have no telephone. They are anxious to learn about the safety of the Minns family. Anyone having knowledge about their safety should contact us here at WWVA immediately so we may notify the Reese family.”

“Mabel,” Tom called out. “Get to the front room window and watch for anyone in a boat. See if you can get their attention and let me know when they get close enough to talk to.”

Mabel followed Tom’s direction and 20 minutes later managed to catch the attention of men in a rescue boat by waving a big red blanket out the window. She called for Tom.

“I’m Tom Minns,” Tom shouted down to the men when Mabel told him they were close enough to hear. “WWVA announced that there have been calls asking about our safety. Please tell them that the Minns family is okay so they can get the word out.”

“They heard you Daddy and they waved,” Mabel said.

Thirty minutes later, the WWVA announcer said that the Minns family was safe and accounted for and the relatives in Buckhannon had been notified.

Weeks of recovery followed and the city’s residents continued to rely on WWVA for critical bulletins and alerts that helped guide those efforts.

Life eventually returned to normal for the Minns and the other folks of South Wheeling. As for Tom’s radio, he never again questioned his decision to buy it.

Coming next is Tom’s Radio Part Two: It’s Wheeling Steel and the WWVA Jamboree

Read more Mabel Files:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Lindy Visits Wheeling

Part 3: T.J. Minns and his “Pal”

Part 4: Music, talk, and danger inside the Minns’ Confectionary

Part 5: Stogies, Sandwiches, and Crocheted Lace

Part 6: The Minns Confectionary Feels the Loss of a Jazz Giant

Part 7: Wheeling’s Underworld and Big Bill

Part 9: Wheeling’s Bonnie and Clyde