Tom Minns drummed his fingers on the glass candy counter and let out a heavy sigh. Lizzie sat in her usual chair next to the doorway that led from the store to the family’s living quarters. A ball of string was in her lap and she worked the metal crochet needle silently in her slim but strong hands. There had not been a customer in the store for hours.

Tom Minns drummed his fingers on the glass candy counter and let out a heavy sigh. Lizzie sat in her usual chair next to the doorway that led from the store to the family’s living quarters. A ball of string was in her lap and she worked the metal crochet needle silently in her slim but strong hands. There had not been a customer in the store for hours.

Tom and Lizzie weren’t used to the quiet and they certainly weren’t pleased about their dwindling income. For almost 30 years they had operated little confectionaries throughout South and Center Wheeling that were alive with activity. Neighbors dropped by to purchase cigarettes and candy and discuss the day’s events on their way home. Generations of young people had loafed in the stores, talking, flirting, listening to programs and political speeches on Tom’s old radio, and discussing the issues of the day. Even impromptu dances had broken out when Tom’s friend Chris Cerone popped in to belt out boogie-woogie tunes on the piano. Tom’s store had been a refuge for human interaction and entertainment during the ups and downs of the Great War, the high times of the 1920s, and the tough days of the Great Depression. But now, during the second great worldwide war, things had become challenging.

Tom, Lizzie and Mabel were not sharing in the return of the local economy’s good fortunes. The industries of the Ohio Valley were back in action in a big way doing their part for the war effort. Wheeling’s Stifel factory turned out thousands upon thousands of Army fatigues that were worn by military forces all over the world. Wheeling Steel was pumping out a wide variety of wartime products like steel drums that were used to carry fuel and supplies to troops in the field. Another major Wheeling Steel product was the steel grid panels that Navy Seabees used to fashion airstrips on Pacific Islands. Thousands of American bombers and fighter planes took off and landed from metal platform surfaces crafted in Wheeling.

Coincidentally, and as if to accentuate Wheeling’s contribution to the war effort, Tom and Lizzie’s new son-in-law, George, had spent much of his time in the Aleutian Islands dressed in fatigues from Wheeling as he unloaded Wheeling Steel-made grid platforms that were installed as warplane landing strips.

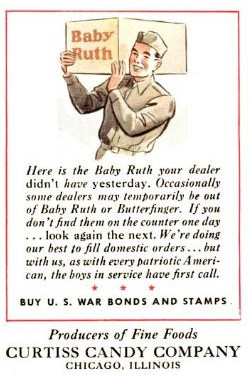

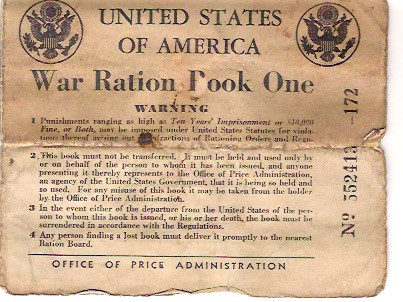

There were more people working in the Valley, and they had more money to spend. But that didn’t necessarily translate to more business if you ran a little store that sold pop and candy during wartime. Sugar rationing had taken its toll on store shelves. Candy that was once popular and plentiful was either not being made in the quantities that it once was, or it was immediately diverted to the troops in the field where candy was almost as essential to morale as cigarettes. That meant shops like Tom Minns’ little store had a lot less candy and sweet drinks to sell.

In addition, the ranks of Tom’s customers had been significantly thinned with many young men away fighting the war. West Virginia had a particularly impressive record of sending its young people to the cause, and Wheeling was no exception. The state had the fifth-highest percentage of servicemen during the war. More than 218,660 West Virginians, including many from Wheeling like George Griffith, were in uniform during World War II. More than 5,800 West Virginians did not come home. When Tom and Lizzie’s daughter, Mabel, read the local casualty list aloud, they recognized too many names of boys who had once spent time as loafers in Tom’s stores.

loafers in Tom’s stores.

In 1941, Tom began to supplement the income from his little store by selling products door-to-door in South, Center, East, and North Wheeling one or two days a week. He would load up his little homemade cart with brooms, mops, ironing board covers, and other household items and show them for sale to every household that would entertain his pitch. It was hard work that required assistance from a revolving crew of neighborhood boys Tom would hire, reasonably good weather, and plenty of patience. But, for every slammed door or disparaging comment he encountered, there would be two or three good sales, and the Minns family struggled along.

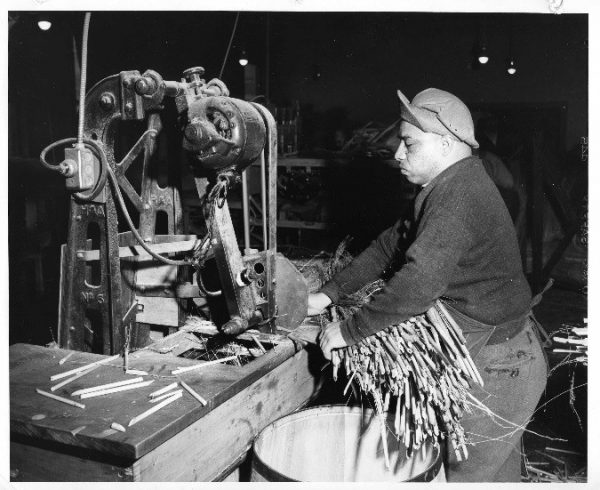

The products, brooms, mops, tea towels, clothespin bags, aprons, pillow cases, and a host of other items, were made by about 100 blind men and women who operated lathes, sewing machines, rotary machines, and hand tools in a busy little factory on Craig Street in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh. Their enterprise was simply known as the Pittsburgh Blind Association. Today, they don’t make brooms anymore, and the company is known as Skillcraft. It started out as part of the National Industries for the Blind—a depression-era organization created by the Roosevelt Administration to help blind people lead more independent lives. Tom would send them a letter and a check once a month, and they would ship him his inventory.

Tom’s alliance with the organization was a natural. He worked all his life to attain an equal playing field for blind people because of the many injustices he had endured himself. He never forgot the crazy cruelty of some Wheeling landlords who had frequently refused to rent an apartment or storeroom to Tom and Lizzie because they believed that blind people would be a risk to the property. They had the unreasonable fear that blind people couldn’t take care of themselves and would end up burning the buildings down. Throughout the 1940s, Tom and his good friend Chris Cerone would become more and more militant about standing up for the rights of blind people—a struggle that would eventually culminate in the formation of state and local chapters of the National Federation of the Blind to raise awareness and fight legislative battles on the state and federal levels.

Heinz History Center Library and Archives

The products were quality made, and Tom’s customers were very happy with their function and durability. But, Tom’s most popular offerings continued to be the beautifully crocheted lace that his wife, Lizzie, crafted at home and, of course, her homemade cakes, cookies, and pies.

On June 4, 1944, Mabel came home from her work at the Wheeling Electric Company with information that further complicated the Minns’ precarious financial situation. Her services in the company offices on 16th Street in Wheeling were no longer required. The company had a policy denying jobs to married women. Since Mabel had married George in April, she was no longer eligible to hold her job running the company addressograph machine.

George had been sending all his Army pay and barber fees home for three years, but that money went into a special banking account the family established to buy a house after the war. Scarcity of everyday operating funds were now presenting problems. Tom was forced to think more strategically.

“Lizzie,” Tom said on that slow afternoon in the store. “I’ve been thinking. You know when we had that telephone installed in the apartment, I thought it was just a convenient thing to have for you and Mabel to keep in touch with our friends and take care of simple business. But, I think there’s a way we can put it to work for us. Instead of putting in all those hours and steps going door-to-door in every neighborhood in the city, why don’t I just call people on the phone to sell our products?”

Tom reasoned that by taking orders on the telephone that he could deliver later, he could cover much more ground and generate additional revenue.

Lizzie stopped crocheting.

“Well that sounds interesting Thomas, but how on earth would you know whom to call and in what order?” she said. “The regular phone book just lists names and numbers alphabetically for the whole city.”

To be effective, Tom had to call potential customers street-by-street. That’s where Mabel came in. Using a regular phone book, she undertook the arduous task of creating lists of phone numbers by street address—all by hand. It took hours and hours. Years later, the family invested in a product called the Haines Criss Cross Phone Directory that listed phone numbers by street addresses, but that was a luxury for the future.

In the afternoons when the store was quiet, Mabel would sit down with her long lists of names and telephone numbers. Tom would sit across from her at the dining room table and make the calls.

Mabel would call out the potential customer’s name followed by the telephone number. Tom repeated the number for the operator who connected the call (when dial telephones finally became available, Tom, and later Lizzie, would strategically place their fingers in the rotary dial holes and dial the number). When someone answered, Tom went into his pitch after first addressing the answering person by name.

“Good afternoon,” he would begin with a script he had memorized. “This is Thomas J. Minns calling. I’m a blind businessman here in Wheeling, and I’m selling a wide variety of household products made by the blind, and a beautiful selection of hand-crocheted lace and homemade baked goods created by my wife, Lizzie, who is also blind. We have brooms, mops, tea towels, ironing board covers, aprons, and clothespin holders. We also have my wife’s applesauce cake, dinner rolls, and apple pies. If you order today, I can deliver on Thursday. Can I interest you in one of our products?”

The business was a hit. Wheeling residents began to anticipate his calls and would save up their product orders until they received Tom’s calls every six months or so. Tom was able to call most every household that had a phone in South, Center, East, and North Wheeling at least twice a year. After more than 30 years, Tom and Lizzie began to give serious thought to getting out of the confectionary business.

By 1945, Tom was spending most afternoons on the telephone. Some calls were all business. Some calls digressed into discussions about sports, entertainment, or city politics. Thanks to the radio, his books for the blind and his ever expanding network of friends, Tom was proficient in all those areas and more and his Irish gift of gab never failed him. Most calls were pleasant. Some were not.

One day, he made a call to a number Mabel called out, delivered his pitch and received an unexpected response.

“Look friend, I’m only here in this backwoods hole to get my sister to move out once and for all,” came an angry voice through the big black telephone receiver. “You West Virginians are just plain lazy, and that’s disgraceful when so many of our boys are out fighting for this country. Now you have the nerve to play the ‘poor-me-I’m- blind’ card in some sort of effort to get my money?”

Mabel wasn’t privy to the other end of the conversation, but she noticed a physical change come over her father’s face that she had not seen very often. His mouth turned down at both ends in a frown that was hardly ever seen. Deep furrows appeared on his forehead, and his ears began to turn red. It was an anger he seldom displayed.

There are few things that Thomas J. Minns would become agitated about. The way blind people were sometimes ill-treated by sighted folks was one. Slurs on West Virginia in general and Wheeling in particular were two others that were sure to provoke a snarling but articulate verbal response. This day, the snippy man on the other end of the call had managed to touch upon all three. Tom wound up and delivered.

“First and foremost,” Tom began in a voice somewhat louder than Mabel was used to hearing. “I am not your ‘friend.’ As for your other rather weak assumptions about blind people, this city, and this state, allow me to educate you so you don’t run back to wherever you came from without knowing some facts about the people you have insulted.

“You may never have heard of them but men with names like Boggs, Brady, Chapline, McColloch, Sheperd, Wilson, and Zane were some of the first people to live here, and they fought hard in the Revolutionary War. They set a wartime example of service that is tough for any state in the union to match, but generations of other West Virginians have followed.

“In the Civil War, it was a Wheeling native – General Jessie Reno – who led troops at Second Bull Run and Chantilly before he was cut down in the Battle of South Mountain by a rebel sharpshooter. Surely you have heard of Reno, Nev., or Reno, Pa. They are named for him. He’s only one of thousands of West Virginians who fought and died in that war.

“West Virginia mustered 58,000 troops for World War I. Five thousands didn’t come home. One of them was Louis Bennett Jr. who, as a member of the Royal Air Force, was West Virginia’s only World War I fighter ace with 12 combat kills. There’s a statue of him at Linsly Military Academy here in this town you call a backwater. Sgt. Felix Hill and Marine Pvt. Raymond White, both from Moundsville, received the French Croix de Guerre. Many West Virginians are buried in cemeteries in France.

“And in this war, West Virginians are making a similar mark. Felix Stump from Parkersburg commands the aircraft carrier Enterprise. He’s already got a silver star. Chuck Yeager from Lincoln County became an ace in a single day by shooting down five German planes. George Roberts of Marion County is the first black cadet in the Army Air Corps and commands two pursuit squadrons. Richard Sutherland of Randolph County is the chief of staff to General McArthur. Woody Williams of Fairmont got the Medal of Honor at Iwo Jima for taking out Jap machine gun nests all by himself.”

Mabel just sat transfixed by her father’s impromptu sermon.

“Two thousand West Virginia women are in military service including Ruby Bradley, an Army nurse who was a captive of the Japanese in Manila and still managed to earn two bronze stars for assisting in more than 230 operations and delivering 13 babies,” Tom continued.

“West Virginia factories have churned out gun barrels, ocean-going vessels, and patrol boats, synthetic rubber, steel for battleships, tanks and other equipment. So don’t tell me West Virginians don’t do their part for this country when they are needed. This city and this state have given everything and received little respect in return. That stops with me, and it stops right now with you.

“As for the ‘blind card’ you say I’ve played. People who cannot see are some of the most hard-working, industrious and creative people you will ever meet. I know men and women who could out think and out produce sighted people without straining. I have worked hard in this city for more than 30 years to make an honest dollar, help people when and where I can, raise a daughter, and support a little family. I’ve delivered newspapers, sold items door-to-door, sold confections from a bunch of little stores, and even made and sold sandwiches to factory workers at lunchtime. I’ve never expected something for nothing. I’m selling dependable quality products at a fair price made by blind people like me who work hard for their wages. So, mister, since you obviously don’t know what you are talking about when it comes to blind people, Wheeling, and West Virginia, I’ll take no more of your time. Good day.”

Mabel sat wide-eyed at the scene. She had never seen her father so worked up. She looked at him closely as he sat back down in his chair winded from his speech and exhausted from telling off the rude man. She noticed for the first time how much he was beginning to age. It was that moment for her when children notice the slow but inevitable decline of their parents for the first time, and it made her sad for a moment until she began to think about the speech she had just witnessed. After all these years, she continued to be impressed by her father’s command of history, his love of his hometown and how he never hesitated to do what he thought was right.

She pushed her chair back from the table, walked over to him, bent down, kissed the top of his shiny bald head, and told him she loved him.

“Who’s next Mabel,” he replied. “We have time for a few more calls before supper.”

Feature photo: “Photograph of Women Working at a Bell System Telephone Switchboard (3660047829)” by The U.S. National Archives – Photograph of Women Working at a Bell System Telephone Switchboard. This media is available in the holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the ARC Identifier (National Archives Identifier) 1633445. Uploaded by LongLiveRock. Licensed under No restrictions via Wikimedia Commons.