Wheeling’s Centre Market, and the shops nearby like Tom and Lizzie Minns’ Confectionary on Market Street, were at rest on Sunday afternoon, Dec. 7, 1941, while the USS West Virginia and USS Tennessee were on fire at Pearl Harbor. Although not as hectic as a Saturday in warm weather months, the day before had been another busy day at the Market. People from miles around had come once again to either sell or buy food, preserves, and other goods. Tom’s store had a particularly good day with plenty of first-time visitors complementing his usually active crew of regular customers.

On this Sunday, like most, Tom, Lizzie and Mabel sat around the big oak dining table in one of the back rooms of the confectionary that served as their family room/dining room. Mabel was reading a story in the paper out loud to her blind parents. Lizzie, as usual, had crochet work in her lap, and she worked the needle in a constant effortless motion preparing another section of intricate lace that Tom would later sell to some Wheeling housewife on his door-to-door rounds. Tom sat at the table and listened intently to all the news Mabel imparted in her elocution-styled readings. Pal, Tom’s aging longtime, home-trained assist dog slept at his feet. Old age was creeping up on the little dog, and he wasn’t quite as feisty as he used to be. Mabel’s fiancé, George, was in Alaska with the U.S. Army, snagged in the second national draft call as the nation prepared for the possibility of war. He was safe for now. Tom took out his pocket watch, opened its cover and felt for the position of the hands on the watch before interrupting Mabel’s reading of the society page.

“Hey, it’s 2:30,” he said clicking the watch shut and reaching for the radio on the little table behind him. “Time for ‘The World Today.’” ‘The World Today’ was a CBS broadcast that aired every Sunday and offered a roundup of national news of the week. Tom adjusted the volume and frequency finder until the broadcast came in loud and clear. The Spirit of ’41, a musical program, was just wrapping up. Then, there was an unusual amount of static and dead air coming through the little radio’s speakers.

CBS announcer John Daly’s voice finally pierced the airways with no introduction or fanfare. “The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor by air, President Roosevelt has just announced,” Daly said. “The attack also was made on all military and naval activities on the principle island of Oahu.” CBS’s John Daly broke the news of Pearl Harbor to the Minns Family at 2:30 p.m. on Dec. 7, 1941.

There was silence for a nearly a whole minute before CBS reporter Albert Warner’s voice came through from Washington. Lizzie stopped crocheting. Mabel put down the paper. Tom leaned in and increased the volume, rousing Pal from his sleep.

Warner’s voice came through reporting from Washington: “The White House is putting out a statement on the Japanese attack. The attack was made on all naval and military activities on the principle island of Oahu. The president’s brief statement was read to reporters by Steve Early, the White House Press Secretary. A Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor naturally would mean war. Naturally the President would ask Congress for a declaration of war. There is no doubt that such a declaration would be granted. The two Japanese envoys, Namura and Kurusu are at the State Department in a meeting with Secretary Hull. Hostilities seem to be opening over the entire South Pacific. Regardless of what the diplomats are saying, Japan has now cast the die. Yesterday Japanese troops were steaming for Thailand. It was based on this information that Roosevelt sent a personal message to the Emperor of Japan last night, a message of restraint and peace. If the Japanese attempt to attack Thailand, or have attacked Pearl Harbor, the delicate balance of peace is destroyed. The Japanese have been warned not to attack Thailand, that if they did, it would mean counter military action. The meeting with Secretary Hull was requested by the Japanese envoys. The meeting was to begin at 1:45 p.m. They arrived late, and were kept waiting. They did not meet with Hull until 2:20. In the meantime, the president was preparing the statement that Japan was attacking Pearl Harbor from the air. It may be that the envoys wanted to assure Hull that the reports of Japanese troop movements in Indochina were exaggerated. Speculation on the steps that would be taken, possibly beginning today, if the Japanese did attack Pearl Harbor. Just now comes the word that an attack has taken place on army and navy bases in Manila. We return you now to New York.”

There was more silence on the airwaves as if the voices were attempting to organize their thoughts before continuing. Tom, Lizzie, and Mabel sat in shocked silence. They began to hear voices out on the street in front of the confectionary. “Mabel, go unlock the front door,” Tom said. “We can’t open for business, but we can be a gathering place for folks who need to talk about this. We are going to war, and there’s going to be a lot of people in a state of agitation. I’ll bring the radio out to the store so we can all keep up together.”

“What about George?” Mabel cried out. “What will happen?”

“Keep a cool head now, Mabel,” her father replied. “We need to get all the information we can. The boy will be fine. He’s in good hands. He’s been well-trained, and he knows what to do.”

The streets around the market house were usually quiet on a Sunday afternoon, but today they came alive with activity. People milled around picking up bits of information from harried conversations. Radios could be heard through open doorways of shops along the streets that were usually closed tight on Sundays. A child could be heard asking, “Why is mommy crying?” The crowds grew. Angry men began to shout about “Jap aggression” and “sneak attacks.” Others began to agitate about “the Nazi threat” and the possibility of German spies in their midst. It was anger, mixed with fear, and fueled by a desire for revenge.

Tom’s store filled up fast. Young people sat on the pop cooler and on overturned wooden boxes. Tom’s radio was kept on all afternoon to catch news reports. Regular programming had been suspended. Parishioners flocked to St. Alphonsus Catholic Church up the street for the 5 p.m. mass, and the bells of the church seemed to ring louder and harder than normal to the assembled people on the street. Mabel and Lizzie made sandwiches, brewed coffee, and served the people in the crowded little store throughout the vigil.

Finally, at 7:30, Eleanor Roosevelt’s distinctive voice came through the airways. For more than a decade, she had broadcast on Sunday nights with her own program called “The American Coffee Bureau.” On this night, the format was unfamiliar.

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen,”

she began as Tom called for quiet in the store. “I am speaking to you tonight at a very serious moment in our history. The Cabinet is convening, and the leaders in Congress are meeting with the president. The State Department and Army and Navy officials have been with the president all afternoon. In fact, the Japanese ambassador was talking to the president at the very time that Japan’s airships were bombing our citizens in Hawaii and the Philippines and sinking one of our transports loaded with lumber on its way to Hawaii. By tomorrow morning the members of Congress will have a full report and be ready for action. In the meantime, we the people are already prepared for action. For months now the knowledge that something of this kind might happen has been hanging over our heads, and yet it seemed impossible to believe, impossible to drop the everyday things of life and feel that there was only one thing which was important — preparation to meet an enemy no matter where he struck. That is all over now, and there is no more uncertainty.

“We know what we have to face, and we know that we are ready to face it. I should like to say just a word to the women in the country tonight. I have a boy at sea on a destroyer; for all I know he may be on his way to the Pacific. Two of my children are in coast cities on the Pacific. Many of you all over the country have boys in the services who will now be called upon to go into action. You have friends and families in what has suddenly become a danger zone. You cannot escape anxiety. You cannot escape a clutch of fear at your heart and yet I hope that the certainty of what we have to meet will make you rise above these fears.”

Mabel, like millions of other women across the city and the nation, felt like Mrs. Roosevelt’s words were aimed directly at her, and she pulled a much-used handkerchief from her pocket and dabbed her eyes.

“We must go about our daily business more determined than ever to do the ordinary things as well as we can, and when we find a way to do anything more in our communities to help others, to build morale, to give a feeling of security, we must do it,” the First Lady continued. “Whatever is asked of us, I am sure we can accomplish it. We are the free and unconquerable people of the United States of America. To the young people of the nation, I must speak a word tonight. You are going to have a great opportunity. There will be high moments in which your strength and your ability will be tested. I have faith in you. I feel as though I was standing upon a rock, and that rock is my faith in my fellow citizens.

Mrs. Roosevelt’s talk was the first the nation had heard from anyone connected with the government since the attack, and her words had a strong effect on the mood of the crowds at the Centre Market. A group in front of the butcher shop up the street began to sing “Onward Christian Soldiers”; men and women across the street that a few moments before resembled the beginnings of an angry mob pulled off their caps and held them over their hearts; the few cars on the street honked horns; and a teenage boy waved a huge American flag on a makeshift pole as he stood on the roof of one of the Centre Market’s adjoining buildings. For the moment, the citizens of Wheeling who gathered in that important Center Wheeling neighborhood were united in grief, inspired by the call to help others, concerned about their young men already in uniform, and energized by the determination to fight back.

When Tom, Lizzie and Mabel turned off the lights and locked the front door of their little store late that night after the crowds had gone and the quiet descended, they began to mentally prepare for yet another era of challenge—this time accentuated by concern for a loved one who was about to be drawn into the dangerous conflict in a cruel, far-off and inhospitable land.

More than 4,400 miles away at Ft. Greeley in Kodiak, Alaska, PFC George Griffith learned of the attack on a crowded field where he and his fellow soldiers, many of them from Wheeling, were part of the 201st Infantry, which deployed to Alaska in April. They now stood at attention in long crisp lines. The wind whipped their fur-rimmed Army green parka hoods as their commanding officer read President Roosevelt’s brief statement about the attack, his high serious voice amplified over the outdoor public address system. It wasn’t until they were formally dismissed that there was any noticeable reaction among the troops. Ft. Greeley was one of the coldest regions in the U.S., and moose wandered freely around the rugged installation. Daylight ranged from 24 hours a day in the summer to just four hours in the winter. The base was officially on alert, and its West Virginia boys were on edge as they prepared for the unknown.

On Dec. 8, like most other workers in Wheeling and across the nation, Mabel dragged herself into work in a daze. She worked at the Wheeling Electric Company on 16th Street and operated an addressograph machine. But, not much work was done that day. Many employers allowed radios to play at work sites to keep up with the news. At 12:30 p.m. all stations carried President Franklin Roosevelt’s address to a joint session of Congress that has since become known as the “Day of Infamy Speech.” Everyone stood in silence around the radios that were scattered throughout the office complex as the president delivered his address calling for war against Japan. Mabel held hands with another woman as they leaned against their desks and occasionally dabbed their moist eyes with handkerchiefs. The speech was frightening in its content but dedicated in its resolve. Mabel had goose bumps as she heard Roosevelt explain what had happened the day before.

“With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounding determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph,” Roosevelt concluded in his seven- minute address. “So help us God. I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.”

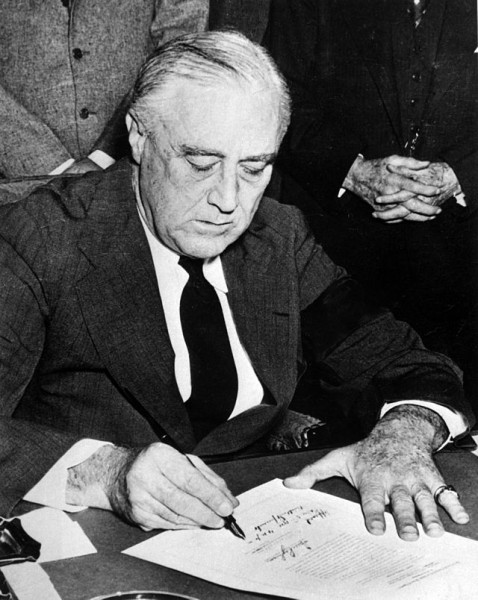

Some of the assembled employees sobbed; others stared solemnly ahead without emotion. Still others prayed silently. Most people went home early that day to be with families and contemplate the challenges ahead. FDR signed the U.S. declaration of war on Japan on Dec. 8, 1941. Meanwhile, leaders of the U.S. Army and Navy as well as the military leaders of the Empire of Japan all studied maps and considered war strategies. The attention of both sides was consistently drawn to a thin series of remote and forbidding islands that extended from Alaska and divided the northern reaches of the Pacific Ocean from the Bering Sea—islands that PFC Griffith and other Wheeling boys of the 201st Infantry would call home for the next four years.

To hear Eleanor Roosevelt’s Dec. 7 radio address on Pearl Harbor attack, visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4unsg4W0JTM.

To hear President Roosevelt’s address to a joint session of Congress on Dec. 8, visit: http://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=dec+7+pearl+harbor+speech&qpvt=Dec+7+Pearl+Harbor+Speech&FORM=VDRE&adlt=strict&mid=D70A679C1C0631B657CCD70A679C1C0631B657CC#view=detail&mid=D70A679C1C0631B657CCD70A679C1C0631B657CC.

To read about CBS’s The World Today radiobroadcast of Dec. 7, visit: http://www.authentichistory.com/1939-1945/1-war/2-PH/19411207_1431_CBS_The_World_Today.html