The Monster in the Basement, Washing the Car in Wheeling Creek, and the New Arrival

In 1947, the Minns/Griffith family enjoyed post-war prosperity. Their little white house on Wood Street in Wheeling where Mabel, her husband, George, and her blind parents, Tom and Lizzie Minns, blended into one jolly family was a happy place in the late 1940s. But, it was about to get a bit more crowded in a way that brought even more happiness.

Tom’s telemarketing business was doing well. Lizzie and Mabel cooked and baked up a storm, specializing in dinner rolls, applesauce cakes, beef dishes, macaroni and cheese, fried chicken and potatoes in many forms (but absolutely no vegetables). In the evenings, George relaxed with Zane Gray western novels after hard days on his feet delivering mail on a route in Elm Grove. Tom turned to the family radio and a big wooden rocking chair to wind down. The only wrinkle in their comfort came in the colder months when George and Tom would have to go down to the basement and do battle with the hulking beast that the family counted on to keep them warm.

It was an American Standard/Sunbeam Octopus Furnace—a coal-burning, hot-air monstrosity that had a hunger that could only be satisfied with shovels full of dusty black coal on a regular basis. It had ductwork jutting out at odd angles that fed heat to various rooms of the house, which led to its Octopus nickname. There wasn’t an electric fan on the system to force warm air upstairs. It was a gravity furnace that heated the air and kept the upstairs rooms warm when the hot air slowly rose through the duct system. Sometimes it belched smoke. Sometimes its flue would stick and require tinkering to work correctly. Sometimes it seemed to groan and make even odder noises. A coal truck delivered bulky black rocky fuel to the house periodically and dumped it noisily down a feeder shoot from the street where it would settle in a coal pen next to the beast, kicking up black dirt and grime on its descent. It was an inefficient, dirty, and noisy way to keep warm.

When Mabel announced with great glee and fanfare that a baby was on the way, George and Tom began to conspire to rid themselves of the inefficient, attention-demanding, basement-dwelling creature once and for all and install a furnace capable of providing nice comfortable heating for the new arrival.

The problem was that George and Mabel’s room didn’t have any ductwork to accommodate forced air heating. It was a rear room that was added on long after the original house was built. While the house had a basement, the added room in the back had only a crawlspace that was too small for heating ducts. There was only one answer, if there was to be a brand spanking new forced air gas furnace in the family’s future, the crawlspace would need to be enlarged and that would require a major digging project. They saved enough money to buy a furnace and have it installed. They did not have the money for an excavation project to go with it. But, Tom and George had a plan.

Every hot summer late afternoon for three weeks in 1947, George and Tom stripped to the waist, took up their digging tools and headed into the crawlspace mostly on their hands and knees determined to prep the area for new ductwork. A weary mailman and a blind entrepreneur pushing 63 were unlikely candidates for a job of that magnitude but they were relentless and focused. George came up with the idea of tying a rope from the opening of the crawlspace to their work area so Tom could follow it in and out. That was important because after digging the dirt, it had to be hauled out in an old cloth tarp and dumped in the back yard where it would be picked up later by a friend with a truck.

Tom and George made trip after trip in and out of the crawlspace digging and hauling dirt in the sweltering heat. The only light in the area came through a small ground-level window at one end of the crawlspace. When George complained that he couldn’t see when the sun went down and it got too dark, Tom issued a mocking laugh, told George to get out of the way, and kept digging. That’s when George rigged up an extension cord and an old work light so he could keep up with his father-in-law.

Even though they had been close for nearly a dozen years, the hard work in close proximity allowed them to form an even tighter bond. The opportunities for them to speak to one another without their wives present were very rare. The project was giving them the freedom to share more than ever before.

George told Tom of his loneliness and boredom during his war years in Alaska. He described the fear, cold, and discomfort he experienced on the long beach patrols he performed all by himself on watch for a Japanese invasion. Tom told George about the hardships he and Lizzie faced as blind parents of an inquisitive adventurous toddler and of their daily struggles with money. George was shocked to learn of the prejudice the little family often faced when some Wheeling landlords would refuse to rent to them because they were blind.

“There are good people in Wheeling,” Tom told George as he wiped sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand. “Oh sure there have been crackpots who couldn’t see past the fact that we were blind, but I’ve been proud to call this city my home because of the people I’ve met who recognized that there is more to surviving and being a good person than having a good set of eyes. By and large, the people here care about each other and as long as that continues, this place can’t fail. Lizzie and I have led good lives, helped people when we could, worked hard for ourselves and raised a darn good daughter. I can’t think of any other city where we could have been as successful as we have been here. Don’t ever abandon Wheeling, George. It’s a place where you can raise your children, and they will have a bright future.”

“I know Pap,” George responded. “I can’t picture myself anywhere else.”

“One more thing,” Tom said slowly. “We are very proud and honored to have you in our family. You are certainly more than just our daughter’s husband. You are a son I never had and you bring us more joy than I ever imagined because you make Mabel happy. I thank you for that.”

George took a long drink from the glass bottle of water they brought into their cavern project.

“Thanks Pap,” he said. “This is really the only family I have ever had and I have always loved you and Abbie (George’s nickname for Lizzie) for taking me in without question.”

“That’s good, boy,” Tom responded. “Now let’s get back to work.”

When the gas furnace installers arrived on the scene in late August, they were shocked at the amount of work the blind man and his son-in-law had accomplished. By September 1, they were all set for winter and ready for the arrival of George and Mabel’s first born.

In 1947, the folks in Wheeling who had cars liked to drive them a couple miles up Big Wheeling Creek to an accessible place where they could drive right down into the shallow water and wash away the dirt and dust that coal-fired city of industry frequently deposited. Because it was unusually warm on September 22 George packed Tom, Lizzie and Mabel into their hulking old Hudson and drove out the creek to cool off. He pulled the car out into shallow water at their usual spot and commenced washing the city grime off the big old vehicle with Wheeling Corrugating buckets and old rags. There were several other families with the same idea that day. Mabel stayed in the car resting her swollen ankles while Tom, pant legs rolled up to his knees; Lizzie, her hair tied tightly back; and George, in a pair of seldom-used swim trunks, waded in the creek water and wiped down the old Hudson.

“George! Mama! Daddy! I think something’s happening,” Mabel suddenly shouted from the back seat of the huge car. “We need to go.”

They piled in the car leaving buckets and rags floating in the creek and George maneuvered the lumbering Hudson over slippery rocks and up a slight hill and back on the road toward Wheeling. Mabel leaned on her father’s shoulder in the back seat and he gently stroked her hair and

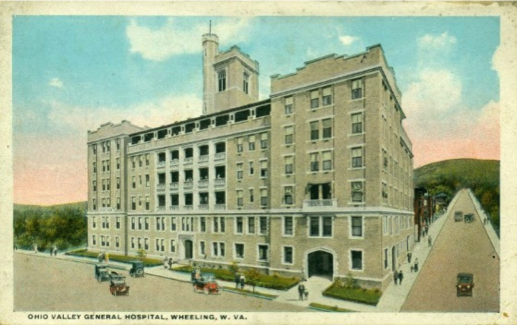

told her that everything would be fine. George stopped at a gas station in Elm Grove and made a telephone call to their family doctor, Earl S. Phillips—they called him Dr. Earl—to report that they were on their way to Ohio Valley General Hospital in anticipation of their new arrival.

On Sept. 23, 1947, their baby arrived with the capable assistance of Dr. Earl. Mabel, and George named him Terrill and planned to call him Terry. No one was more excited than Tom who spent a fortune in dimes hunched over in the tiny phone booth in the lobby of the hospital calling everyone he could think of to spread the word. He would play a major role in the care of the baby, relishing every opportunity over the next several years to bathe, dress and rock Terry from infancy through his toddler days.

The new expanded family spent a warm cozy fall and winter in their Wood Street home courtesy of the brand new forced air gas furnace and the ductwork that George and Tom’s crawlspace adventure made possible. Baby Terry had four parents devoted to satisfying his every whim.

Tom loved being a grandfather. The only problem was the exhaustion he was beginning to battle more and more often.