With a loud click, a wrinkled shaky hand placed 15 cents on the glass countertop of Tom Minns’ confectionary on Market Street on a rainy Thursday morning in late 1944.

“What can I get for you?” Tom asked, unable to see if his customer was male or female or if they had indicated what product they intended to purchase. His query was met with silence. Tom waited. He could hear heavy wheezy breathing and the wooden floor below his visitor’s feet creak indicating an unsteady stance. He could smell a mix of burned tobacco, bourbon, and an odor of personal untidiness. He concluded that a nervous unhealthy individual who may be under the influence was standing just feet away, but there was still no response. Unsure but suspicious, the veteran storekeeper moved slowly closer to his cash box and put his hand in the open drawer below.

“I’ll be happy to get you what you need, but you have to speak up,” Tom said. “I’m blind you know.”

The silence was finally broken by the tinkle of the little bell over the door that served to announce the arrival of customers.

“Uncle Ernesto,” a young man exclaimed. “You can’t wander off like that. We’ve been searching for you. “Sorry Mister. My uncle is just looking for a pack of smokes. He doesn’t speak. Sorry for the inconvenience. Can we get a pack of Camels?”

“Sure thing,” Tom said walking to the shelf behind the counter and pulling down a single pack of Camels. “Sorry I didn’t know he couldn’t speak. Is there anything else I can do? I hope I didn’t offend him.”

“No sir,” the younger man replied handing the pack of cigarettes to his uncle who fumbled to open them. “I’m sure he wasn’t offended. You see, he hasn’t been quite right since the Benwood disaster 20 years ago.”

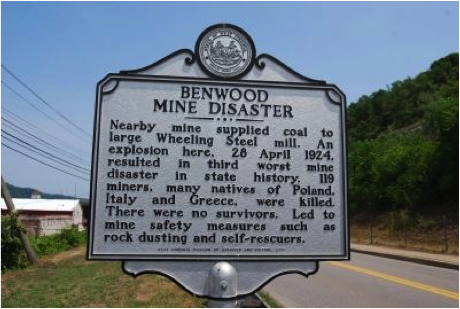

As with most folks from Benwood and South Wheeling, mention of the mine disaster of 1924 sent pangs of sadness and curiosity pulsing through Tom’s thoughts. It had been a disaster that focused the attention of the entire country on the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia and claimed the lives of 119 friends and neighbors.

“Really,” Tom said. “Was your Uncle Ernesto involved somehow?”

The young man shifted his weight uncomfortably.

“Do you really want to know about it?” he asked. “If so, I can come back and tell you the story after I take Uncle Ernesto back to our car. He just kind of wandered off while we were shopping for vegetables over at the Market House.”

“Of course,” Tom replied. “Please do come back. I’d love to understand so I can be helpful to your uncle should he ever need anything here again.”

Twenty minutes later, the young man sat on a wooden crate next to Tom’s storeroom chair, savored a bottle of pop, and began the story of his Uncle Ernesto’s brush with fiery death in one of the worst mining disasters in American history to that point.

He explained that Ernesto, his brother, and four cousins had come to America in 1910 when they all had been in their 20s. They searched for work in New York but soon learned that a great many jobs were available in the coal mines of Pennsylvania and West Virginia. They found their way to Benwood and jobs in the mines owned by Wheeling Steel and Iron Corporation.

“Ernesto was good in the mines and was eventually promoted to fire boss,” the young man explained. “That’s a tough job. The fire boss is usually the first person to enter a mine at the beginning of the day to detect unsafe conditions like gases that could cause a fire. Fire bosses would soak their clothes with water and go in. In the early days, they would often walk through the mine with a lit candle on a long stick to detect and ignite gases. Obviously it was dangerous way to keep other people safe.”

When he wasn’t underground, Ernesto’s passion was the game of bocce, an outdoor game that Italian immigrants brought to America. It was a centuries old sport that involved the skill of aiming and throwing wooden balls at a target on the ground. Because the sport was so popular in Europe, the Italians weren’t the only immigrants interested in playing the game after they brought it with them to mining communities like Benwood and Wheeling. It was popular among the Croations and Slovenians as well as the Italians.

“There were bocce clubs sprouting up all over the place back in those days, and they liked to have matches against each other on the weekends,” the young man explained. “Uncle Ernesto was one of the best players, and he played in organized events every single Sunday. On April 27, Uncle and his team were invited to a big match in Cleveland. The trouble was he supposed to start the shift on Monday morning as fire boss. He knew he was going to be tired from the match and the long train trip home so he traded the early shift with another man.”

Tom was beginning to understand where the story was headed. The Monday morning he was supposed to be fire boss, the Benwood Mine exploded, unleashing terror, grief, and ferocious and futile rescue attempts that captured the attention of the reporters and newspaper readers all over the nation.

“What did you say Ernesto’s last name was?” Tom interrupted.

“I didn’t say but it’s Bianchi, same as mine,” the young man replied before picking up his story again.

“The story we got was that there had been a roof fall on the late shift the day before, and one of the first miners in the area on Monday morning thought that the fire boss had already examined the area and found it to be safe,” the young man continued. “The man who took Uncle Ernesto’s place just hadn’t been there yet. So, when the miner entered the area, the open light on his helmet ignited firedamp—that’s a pocket of air with methane, carbon dioxide, and other gases in it. The whole mine went up and slate and debris covered portions of the main entry so the men couldn’t get out.”

Tom remembered well the immediate aftermath of the explosion. He recalled hearing a steady stream of vehicles head south past his little store that was then in South Wheeling on Jacob Street and the shouts of people on the streets. He knew it must have been total chaos in Benwood, less than four miles away.

“The sound of the explosion woke Uncle Ernesto and he headed straight down to the mine to see what was going on and how he could help,” the young man said. “By the time he got there, a huge crowd had gathered. There were women wailing and children crying. No one seemed to know anything. Ernesto grabbed a helmet and a pick axe and headed for where the rescue teams were gathered.

“There was a second explosion not long after the first one that was probably coal dust touched off by the first event. That’s the one most folks say probably killed the most miners. The rescuers couldn’t get in through the main entrance, so they moved over to an air shaft at Browns Run. As the day went on, additional teams of rescuers from as far away as Pittsburgh and Cincinnati began to arrive with their equipment. Some of them had oxygen tanks and masks but others didn’t. It was a real mess and there was a lot of confusion. I heard that a women was hit and killed by a truck taking equipment to the air shaft. Families were wandering the streets confused and in search of someone with answers. I heard one woman threw herself in the river and had to be rescued herself when it was clear her husband didn’t survive.”

Tom was fascinated by the story even though he had heard most of it before. He was still curious about Ernesto’s experience and how it turned a big powerful man mute.

“Ernesto made it under ground as far as he could with a team of rescuers,” the man said. “That’s when the real horror began for him. They began to reach bodies. Some were burned and crushed so bad that no one could tell who they were. Others had rags wrapped around their faces to try to breathe in the gasses down there. It must have been awful. Uncle worked for hours until he nearly collapsed from exhaustion, but he kept on until he made the worst discovery of all.”

Tom was on the edge of his stool.

“He came across a burned body that he only recognized by the boots on the man’s feet,” his visitor said. “He recognized them as his own boots that he had lent out the day before. The dead man at his feet was his brother, my other uncle. That’s when he finally did collapse and had to be carried out of the mine.”

The young man explained that the explosion, the knowledge that he was supposed to be in the mine that morning, the nagging thought that had he been on the job he might have been able to do something to prevent the explosion and the devastating discovery of his own brother’s body, sent Ernesto into deep shock.

“He’s never come out of it,” he said. “He was in bed for months and just stared straight ahead. He didn’t respond to questions or people talking to him. Eventually, he got out of bed and dressed himself,,,,,,, but he has never talked again. He mostly drinks whisky, smokes cigarettes and wanders around our house without showing any kind of emotion or interest in life. He obviously never played bocce again. It’s like he’s trapped inside his head.”

Tom shook his head and recalled his own memories of that awful April day and its aftermath. He remembered his store customers describing the procession of vehicles that brought bodies to a temporary morgue inside the Cooey Bentz store just up the street. He recalled stories of the mass burials at Wheeling’s Mt. Calvary and Greenwood Cemeteries for the men who were recovered but could not be identified because of the severity and extent of their injuries. And he remembered hearing the names of the victims read aloud from the newspaper and being shocked at how many names he actually recognized as former neighbors, friends or customers.

“The doctors say Uncle’s experiences have hurt him in the head somehow,” the man said. “We just help him as much as we can. He must have seen some awful things down in that mine.”

Tom rubbed his chin and thought about the young man’s story.

“That’s horrible,” he said. “I wish there was something I could do to help.”

“Well, if you mean it, there might be something,” the young man said. “The doctors in Cleveland say there’s an operation on his brain that could help, but it would cost a lot of money—money we just don’t have. We are trying to take up a collection. Maybe you would want to chip in $20 or so. It sure would help. Maybe you know some other folks who would want to help too.”

Tom stood. Keeping one hand on the top of the class counter to guide his way, he quickly made his way behind the counter and stood next to the cash register. The young man smiled.

“That’s a pretty good story son,” Tom said. “You got almost everything exactly right. That’s just the way it happened—the grief, the panic of the families, the rescue efforts, the probable cause of the explosion, even the woman who was by the truck. The trouble is, nobody named Bianchi died in the mine that day. I know because I knew men who were underground who didn’t come home. I know all the names. Many were friends and many were my customers. We helped send food to the families for a week after the disaster and I delivered much of it to Benwood myself. So, you see, I’m not unfamiliar with what happened that day. Oh and I had a chat earlier today on the telephone with the lady who runs the flower shop up the street. Seems you told her a similar story, and she fell for it. We folks at the Market House kind of stick together in these sorts of things. I just wanted to see how well you told your story.”

The young man got to his feet and dropped his empty pop bottle on the floor.

“Look mister, you better not tell anybody about his, or things could get bad for you,” he said as he moved forward.

Tom reached in his drawer and plopped his little silver revolver down on the countertop with authority, business end pointed toward the voice in front of him and a finger resting loosely on the trigger.

“I think we can understand each other,” he said. “Now please leave this store and don’t let me hear of you coming around this neighborhood again. I’m sure the families of the men who were lost that day would love to meet your acquaintance. Make sure you take your Uncle with you. He’s probably tired of waiting. Oh and you owe me five cents for the pop.”

The two grifters were never seen in West Virginia again.

For an extensive story about the Benwood Mine Disaster, check out Sean Duffy’s account at: http://www.archivingwheeling.org/blog/no-survivors-91-years-ago-today-in-benwood/

A website that lists the names of all the victims can be found at:

http://www3.gendisasters.com/west-virginia/5492/benwood-wv-mine-explosion-claims-many-lives-apr-1924

For a compilation of news bulletins associated with the disaster, visit: http://www.wvculture.org/history/disasters/benwood03.html