Wheeling Men Endure Isolation, Cold, Grueling Labor, and Air Attacks in the Aleutian Islands

In the early days of World War II, the military masterminds of both Japan and the United States cast strategic eyes toward a string of cold and treeless volcanic islands that protruded into the icy waters of the Bering Sea. Their plans for attack and counterattack by land, sea, and air had implications for the US Army’s 201st Infantry—a division made up mainly of West Virginians and, more specifically, a large number of men from Wheeling, including ex-barber George Griffith, Mabel Minns’ fiancé.

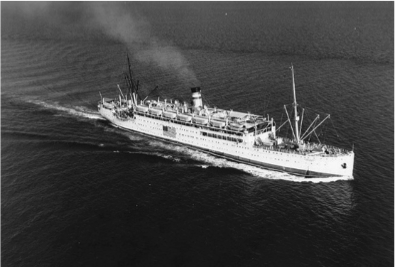

George and the West Virginia boys of the 201st were in Alaska before the attack on Pearl Harbor. They were scooped up in the second round of the draft and transported from Seattle, Wash., to Kodiak, Alaska, in April 1941 aboard the USS U.S. Grant.

The Grant was actually built as a German luxury ocean liner called the Koning Wilhelm II before World War I. She carried passengers in comfort between Hamburg, Germany, and Buenos Aires, Argentina, until the outbreak of war in 1915. To avoid being captured by Britain’s Royal Navy, the liner was voluntarily parked at Hoboken, N.J., but when America entered the war, she was seized by the U.S, renamed, and converted to a troop transport. She took 12,000 Americans to war in Europe and brought 17,000 home after the armistice. Now, she was engaged in the business of moving a new generation of warriors and their equipment into harm’s way.

By the time George boarded her, the luxury conditions of the ship’s previous life were long gone. She could carry 1,244 troops and 211 crew members per voyage. Troops slept in long rows of bunks in big open rooms. At a top speed of 15 knots (about 17 mph) the Grant took more than three days to cover the 1,428 miles from Seattle to Kodiak—plenty of time for land-based West Virginians to deal with sea sickness.

George spent time with buddies and wrote long letters home to Mabel—letters that would be read and heavily censored before finding their way to Wheeling. Because he cut hair in civilian life, his lieutenant designated him as company barber.

Since he was allowed to charge for cutting hair, the assignment allowed him to send extra money home to Mabel for saving. She was working at the Wheeling Electric Company and building up a bank account to buy a house where the couple planned to live with her parents, Tom and Lizzie, after the war.

The Grant finally discharged her troops at Kodiak Island in mid-April. By the time George and his colleagues from West Virginia arrived, airplane runways, offices, docks, and housing for 10,000 people had been built along with bunkers and gun emplacements in a complex they called Fort Greeley. There was plenty of grueling work remaining for the West Virginians of the 201st. When they weren’t drilling and practicing for combat, the men were put on details unloading ships, loading trucks, and performing all the tough tasks associated with expanding the military toehold into a full-scale base of operations. Compared to what was to come, it was easy duty.

The 201st executed scouting missions over rough terrain to strange-sounding locations like Kupreanof Straight, Cape Chiniak and Isthmus Cove to pinpoint good locations for air warning service stations and then lugged heavy equipment and supplies through bad weather conditions, up ragged cliffs of volcanic rock, and over narrow, dangerous trails to mountain peaks where they established sites to watch for enemy aircraft.

When Fort Greeley was fully operational and protected with observation posts by late 1941, the soldiers settled in to await their destiny. George kept a diary and recorded his work assignments and the weather conditions day-by-day—a practice he would continue until the war ended.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, U.S. forces in the islands shifted into full alert and drilled harder but now with anger and determination as motivation.

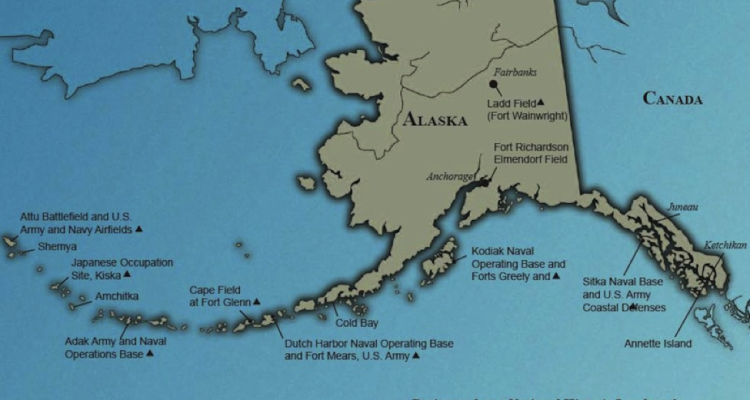

The Japanese eventually made their move on the island chain. In June 1942, they invaded American soil by landing on the barren Kiska and Attu islands, where they set up airfields and began bombing U.S. bases at Dutch Harbor. They were planning to establish another base on a third island in the chain known as Amchitka. U.S. commanders decided to beat them to the punch. The 201st was sent to the forbidding Amchitka Island in January 1943 to take control and help build air strips from where American fighters and bombers could strike at the Japanese.

George wrote in his diary about spending half of his days unloading and hauling heavy equipment and building supplies and the other half on lonely beach patrols watching for signs of the enemy. The Japanese were frequent visitors by air. Japanese Zeros strafed and bombed daily. George wrote about casualties from the enemy’s air attacks noting that, “Tojo strafed us again today. Lost several men.”

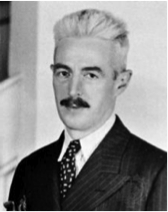

One cold afternoon, a Japanese Zero from the enemy base on Kiska 50 miles away made a bombing run on Amchitka’s busy U.S. forces. George and several others ran for cover and jumped into a foxhole that was already occupied by a grey-haired older corporal who scribbled in an Army notebook as the bombs exploded around them. It was Dashiell Hammett, the famous author of hard-boiled detective stories like The Thin Man and The Maltese Falcon. Hammett had enlisted and been assigned to write a history of the Aleutian campaign.

In a pamphlet he co-wrote with another Army corporal, Hammet described the difficulties of the 201st‘s Amchitka struggle.

“No one who has not seen it can have any conception of the tremendous quantity of supplies and equipment that must be moved from ship to shore,” Hammett wrote. “And, once ashore, all this vast mountain of material had to be transported by hand. Vehicles were of little use in those all-important early days of the occupation. And these men did what they had come to do. They built their airfield. From Jan. 24 on, Japanese planes scouted and bombed Amchitka whenever weather permitted. But by Feb. 18 a new fighter strip was ready for Warhawks (P-40s) and Lightnings (P-38s).”

Enduring fatigue, bitter cold, snow and enemy air attacks, the 201st worked hand-in-hand with Navy Seabees to build the Amchitka airfield that Hammett described. The U.S. now had an operable air base 50 miles away from the Japanese-held Kiska. It was a base that played a pivotal role in giving the Americans air superiority in what was to become the only World War II battle to occur on U.S. soil—the Battle of Attu known as Operation Land Grab.

Eleven thousand U.S. troops landed on Attu on May 11, 1943 but the 201st Infantry was not among them. They remained in the cold of Amchitka on alert and ready for enemy attack. Had they been on Attu, they would likely have had to face one of the largest Japanese banzai attacks of the war when outnumbered and cornered soldiers of the Empire ran head-long into U.S. forces in a last-ditch effort to hold the island. More than 2,000 Japanese soldiers died. The Americans lost about 1,000 men.

On Amchitka, George and the others picked up a few details of the battle from the airmen who landed at their airstrip. Disappointed to be out of the action but relieved to have not been a part of the terror, they dug in and shivered through their guard duty, conducted frozen beach patrols, and battled boredom instead of the enemy.

After their sound defeat on Attu, the Japanese pulled out of Kiska under the cover of fog. It was the end of war action in the Aleutians. The campaign was one of the least talked about encounters of the war and fades more from American memory every year. But, it was Wheeling and West Virginia boys of the 201st who endured the elements, the exhaustion, and the threat of death from the skies to play a key role in the strategy that led to the defeat of the Japanese and their expulsion from American soil.

When he finally came home, George never talked about whether he saw any action during his long lonely beach patrols, and his diary is silent on the topic. Years later, his blind father-in-law, Tom Minns, would handle a sharp and stubby little knife that George crafted out of scraps while on Amchitka and carried with him on the cold, icy beaches.

“Ever stick any bad guys with this, George?” Tom asked curiously one day.

George never answered and, like many veterans, just changed the subject.

NOTE: George Griffith never mentioned the Wheeling men he served with by name in his diaries. Know anyone who served in the Wheeling-heavy 20st Infantry in World War II? Have any stories to share about their service in the Aleutian Islands? Replies welcome.

To learn more about the Battle of the Aleutian Islands, visit http://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/battle-of-the-aleutian-islands

To learn more about Ft. Greeley on Kodiak Island, visit http://kadiak.org/greely/greely2.html.

To learn about the colorful life of the USS U.S. Grant transport ship, visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_U._S._Grant_(AP-29).

To learn about where your father or grandfather’s military unit was stationed on December 7, 1941, visit http://www.navsource.org/Naval/usarmy.htm.

All photos from Wikipedia Commons except pictures of George and Mabel Minns Griffith, courtesy Griffith Family.