Mabel Files 11—Tom’s Radio Part 2

Lizzie Minns had a restless night that Saturday in January 1933. She tossed and turned and couldn’t seem to get  herself to go unconscious. There was no reason in particular for sleep to elude her. It was just one of those nights. Finally, she rolled out of bed a little before midnight and headed into the kitchen of her tiny apartment upstairs in the little confectionary she ran with her husband, Tom, and daughter, Mabel. Lizzie and Tom were blind, so they never switched on the lights at night. Fourteen-year-old Mabel was asleep in a tiny alcove off the kitchen that served as her bedroom.

herself to go unconscious. There was no reason in particular for sleep to elude her. It was just one of those nights. Finally, she rolled out of bed a little before midnight and headed into the kitchen of her tiny apartment upstairs in the little confectionary she ran with her husband, Tom, and daughter, Mabel. Lizzie and Tom were blind, so they never switched on the lights at night. Fourteen-year-old Mabel was asleep in a tiny alcove off the kitchen that served as her bedroom.

Lizzie closed the bedroom door behind her so she wouldn’t wake Tom, picked up her crochet work, and settled into the rocking chair she kept next to the big old coal-burning stove in the kitchen. She reached over to click on the faithful Crosley Justice radio that served as the family’s ears to the outside world. She had never listened to the radio at this time of night, but she felt so wide awake that she wanted something to occupy her mind. Perhaps there was some Mozart or her favorite, Beethoven, on a network broadcast from one of the big cities. She had never fiddled with the tuning knob that found stations. She always deferred to Tom’s taste and radio operation expertise. Whatever station someone last listened to was the station she was going to have to listen to now.

The little radio hummed and buzzed a moment before its tubes warmed up. Then, rather abruptly, it spit out sounds that took Lizzie completely off guard. It was quite a shock to a woman raised on church hymns and schooled on the classics. She dropped her crochet needle and bolted straight upright in her chair.

“What in tarnation is this?” she asked herself out loud. It was harmonica music—a lone performer rocketing through a unique version of a tune that Lizzie vaguely recognized through the musical twists and turns of the stylist’s interpretation. She could even hear the performer’s foot stomping time to the music through the Crosley’s speaker.

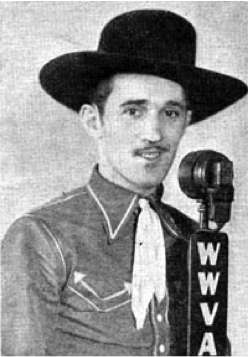

When it stopped, an accented and extremely friendly voice boomed, “Howdy and welcome ladies and gents,” the voice rang out. “I’m Felix Adams, your faithful host and announcer for an entirely new program here on WWVA in Wheeling, W.Va. Yep, that was me on the ole mouth organ playing for you in our studio high in Wheeling’s Hawley Building downtown, and this is the WWVA Jamboree. Tonight, we are featuring Fred Craddock’s Happy Five, the crazy singing trio Ginger, Snap and Sparky, the Tweedy Brothers, and lots more, so settle in, put your feet up and get ready for some home-style entertainment.”

“Mama,” interrupted a sleepy voice from Lizzie’s right. “What is that? What are you listening to?”

Lizzie, who by then was on her hands and knees feeling about for her dropped crochet needle, didn’t know exactly how to respond.

“I’m not sure, Mabel. I’m sorry I awakened you. Please try to go back to sleep. I’ll turn it down.”

“Mabel asks a good question,” Tom said from the doorway into the bedroom. “What in the world are you doing? Your taste in music seems to have taken a rather severe turn.”

“It’s all you fault Tom,” she responded. “I don’t know what you had on the radio last, but this is what’s on now. I’m not all that happy with it, whatever IT is.”

It wasn’t that Tom, Lizzie, and Mabel were musical snobs. But they could be a tad resistant to musical styles that were outside their frame of reference, which Lizzie would demonstrate again 31 years later when the Beatles invaded. They hadn’t owned a radio for very long, and what they had found on their radio during those first few moments of that early Sunday morning in January 1933 definitely fell into that category.

The WWVA that the Minns family usually heard in the daylight hours of the 1930s was a full schedule of news programs, farm reports, and dramas emanating from the CBS radio network. In the evening, they tuned in stations that brought band music for dancing or classical broadcasts from New York. WWVA’s new “Jamboree,” featuring the unfamiliar sounds of country music, kind of snuck up on them.

“Now for your listening enjoyment, we are going to bring out the Sparking Four for some of the best yodeling this side of Tennessee,” came the voice of Felix Adams out of the Crosley’s speaker. “Take it away kids.”

When asked the next day to describe what they heard next on this strange new radio broadcast, Lizzie and Tom had no words.

“They weren’t singing words exactly, and there wasn’t a melody you could really identify,” attempted Tom when a store customer expressed curiosity.

“It was up-tempo and they sang in a falsetto,” Lizzie added. ‘They slurred the notes so it sound like one long vocalization, but they were all over the place with it. I’ve never heard anything like it before.”

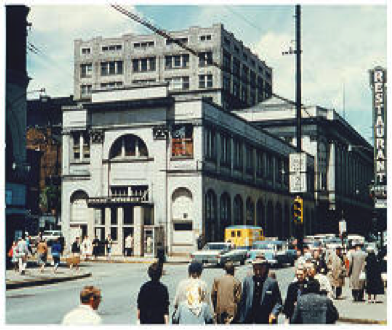

But the Minns’ country music education had only just begun, thanks to WWVA owner George W. Smith. Smith recognized the growing popularity of country music programs in other radio markets where “barn dance” programs had popped up inspired by the music of Jimmie Rodgers, “The Singing Brakeman,” who specialized in yodeling and railroad songs. Smith decided to gather his own performers, pack them into a tiny studio in downtown Wheeling’s Hawley Building (now the Mull Center), and put out a country music program of his own. It was one of the very first broadcasts of the “Jamboree” that Lizzie had stumbled upon in her bid to overcome a sleepless Saturday night.

A vast majority of WWVA’s audience didn’t harbor Tom and Lizzie’s reluctance to embrace the Jamboree. By March  1933, the occasional Jamboree broadcasts were on every Saturday and were eventually moved to the Capitol Theater for live broadcasts that sucked in more than 3,200 people every week who ponied up 25 cents each to see their beloved radio stars in person.

1933, the occasional Jamboree broadcasts were on every Saturday and were eventually moved to the Capitol Theater for live broadcasts that sucked in more than 3,200 people every week who ponied up 25 cents each to see their beloved radio stars in person.

Tom, Lizzie and Mabel didn’t become regular listeners, but every once in a while, Mabel caught Lizzie with her ear to the Crosley speakers and a smile on her face as she listened to country comedians like Dapper Dan Martin, Cy Sneezeweed, Smokey Pleacher, or Lazy Jim Day do their routines between musical acts. But, she never did get used to the yodeling. Whenever a yodeling act came on, Lizzie ended her Jamboree flirtation with a distinctive click of the off switch.

Once in 1938, Mabel and her beau, George Griffith, attended a Jamboree broadcast in person. A friend gave them tickets and offered transportation to and from the Wheeling Market Auditorium, the WWVA Jamboree’s home at the time. She remembered the  delight and anticipation of the crowd when the lights went down and someone behind the stage curtain strummed the first few chords of a song that everyone seemed to know. The curtain opened to reveal the entire cast of the show singing the Jamboree’s theme song in unison. Much of the crowd, but not Mabel and George, joined in singing:

delight and anticipation of the crowd when the lights went down and someone behind the stage curtain strummed the first few chords of a song that everyone seemed to know. The curtain opened to reveal the entire cast of the show singing the Jamboree’s theme song in unison. Much of the crowd, but not Mabel and George, joined in singing:

Now here’s the Jamboree to greet you

In the good old fashioned way

We’ll do our best to please you

And hope that you’ll feel gay

We are more than glad to see you

And hope you’ll be carefree

So laugh and smile with us awhile

On the midnight Jamboree

George, who got plenty of exposure to old time and country music during his time in Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Camps out west, was more acquainted with the music and its performers than Mabel, who remained shocked at the informality of the show.

“They ate peanuts and just threw the shells on the floor,” she told a friend later. “And when they really liked something they shook cowbells. It was really loud!”

They watched as one act after another delighted fans. A spiritual group, the Wheeling Weird Travelers, started things off. Then came a banjo player named Marshall Jones, who would later become Grandpa Jones on television’s Hee Haw decades later. And, of course, there was the biggest Jamboree star of them all in the late 1930s—Doc Williams and his Border Riders. George’s clapping went long and loud when Doc Williams wound up his performance. Mabel just watched in amazement.

“I guess I respect what they do,” Mabel told George on the way home. “I just don’t like the whiney sound of the music.”

Plenty of other folks did like it, however. WWVA’s powerful transmitter sent the broadcast as far away as Newfoundland. Fans from all over Canada and the U.S. began showing up. The train stations became much busier on Saturday mornings, the McLure House was booked, and strange buses with odd license plates began lining the streets on Saturday evenings.

One Saturday afternoon at Tom’s store in South Wheeling, a bus pulled up out front and 30 happy Canadians stepped off. They were lost and looking for the Market Auditorium to attend a Jamboree later that night. They wore boots and cowboy hats and some of the women wore skirts with embroidered images of cowboys roping steers. They were hungry, thirsty and stopped at the first confectionary they saw, much to the Minns Family’s pleasure. They cleaned out the pop cooler and stocked up on candy and smokes for the show later that night. Tom, Lizzie, and Mabel, like a lot of other merchants in Wheeling, began to have a new and much more favorable appreciation for the “Jamboree.”

One evening, in the summer of 1936, some of Tom’s usual customers stopped by on their way home from work at Wheeling Steel’s Benwood Plant. They were buzzing with excitement. They said something about a new radio show that would feature Wheeling Steel employees as the main acts.

“Auditions are tomorrow,” explained Karl, one of the steel workers. “There are about 25,000 Wheeling Steel employees around here, so they ought to be able to find a few who can carry a tune.”

“Carry a tune,” responded Karl’s friend Lester. “I can name a dozen people right now at Benwood alone who could sing rings around Rudy Vallee. Wait till you hear my niece from accounting sing. She’s putting together an act with a couple other gals. They are calling themselves the ‘Steele Sisters.’”

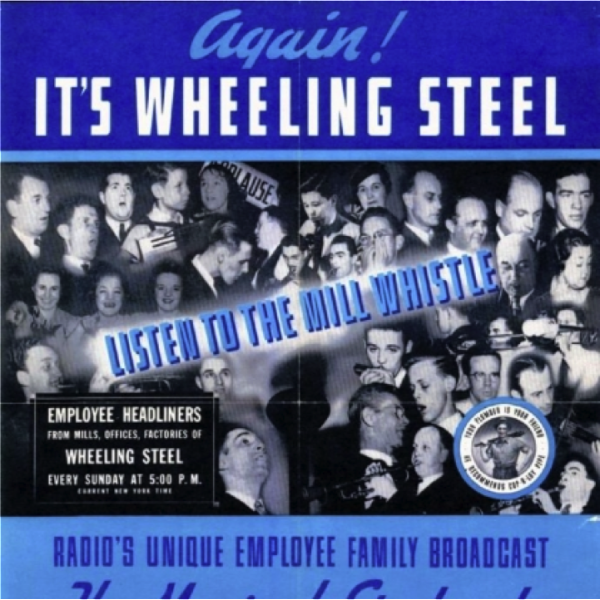

They were talking about a new radio show that would not only be more to the Minns’ liking; it would quickly rival the Jamboree in the fame department. “It’s Wheeling Steel” was the brainchild of the steel company’s advertising director, John Grimes who was seeking not only to bolster national awareness of the company, but also to build up worker morale in the depths of the Great Depression. He envisioned a half-hour variety show that featured Wheeling Steel employees as the featured entertainers.

“It’s Wheeling Steel” took to the airwaves on WWVA on Nov. 8, 1936, and drew a loyal local following including Lizzie, who, while still preferring the classics, begrudgingly had accepted the pop music from swing bands and love ballads as performed by some of her customers as preferable to the yodeling and banjos of the Jamboree.

Eventually, Grimes got his bosses at Wheeling Steel to buy time on the Mutual Radio Network to carry the show on 17 stations from New York to California. Fame came quickly. Before long, “It’s Wheeling Steel,” which began every show with the blast of a steel plant steam whistle, was being featured in stories in LIFE and Time magazines. Billboard and Variety carried features about the steel-making musicians like the “Singing Millmen” and “The Evans Sisters.” Famous bandleaders like Henry Busse and Paul Whiteman began showing up in Wheeling to serve as guest conductors of the show’s big band. Show singers like Regina Colbert and Dorothy Anne Crow became known in homes from Baltimore to San Francisco.

The whole neighborhood gathered around Tom’s radio in the store on June 25, 1939, for a broadcast from the Court of Peace at the New York World’s Fair that featured “It’s Wheeling Steel” for “West Virginia Day” at the Fair. It was a virtuoso performance by the show’s cast that thrilled the 26,000 people who attended the show in person as well as the listeners coast-to-coast. Arden White, who would become the choir director at Mabel’s church, was one of the featured soloists. The citizens of Wheeling were bursting with pride that evening and the folks in Tom’s store were no exception.

Before winding up its series of 327 broadcasts on June 18, 1944, “It’s Wheeling Steel” had been picked up by the NBC network, was carried on 120 radio stations, and played a significant role in supporting the war effort with war bond concerts including the “Buy a Bomber” program from West Virginia University’s Field House in Morgantown, and became the fifth most popular radio show on NBC. The show finished in its prime and only ceased its broadcasts because of the ill health of John Grimes, the guiding light behind the show.

Lew Davies, the show’s music arranger and conductor of record, went on to create musical arrangements for Perry Como and is often credited with successfully duplicating the format for “It’s Wheeling Steel” into what would become the long-running Lawrence Welk television show. (A Saturday night tradition in the Griffith household that Lizzie and Mabel insisted upon through out the 1960s, which irritated my brother and me as we constantly lobbied for a “Rocky and Bullwinkle” alternative to no avail.)

Between the “WWVA Jamboree” and “It’s Wheeling Steel,” Wheeling’s fame soared. For a bright shining time, the city became just as famous for its talented citizens, unique music venues and broadcasts, hospitality, and enthusiasm as it was for its nails, steel, stogies, and colorful underworld. At Tom’s store, both shows brought the customers and proprietors alike a sense of pride, a source of entertainment, and even indirect revenue during the sober days of the Great Depression.

Chuck Miller wrote an outstanding article about the Jamboree for his web site that also features pictures and a few videos.

There’s more about the Jamboree at this site called Hillbillymusic.com.

John A. Cuthbert, curator of the West Virginia and Regional History Collection at West Virginia University wrote a very informative article about “It’s Wheeling Steel” that has links to audio excerpts from the original broadcasts.

photos provided by Gerry Griffith