WARNING: This article contains explicit language and subject matter that is not suitable for children. It is the equivalent of Rated R.

(Writer’s Note: This is the fifth in a series of stories that will concentrate on the organized-crime scene in and around Wheeling during the past century.)

Dynamite, Trained Monkeys, and Dead Broke.

“At 10:25 a.m. this date (Jan. 17, 1964), radio operator Alfred Howard received a phone call from Bill Linton, 4th and Warwood Avenue. Mr. Linton told Howard that a car had been blown up down on 4th and Richland Avenue and a man was in it. Car #5, 10, 11, and (Louis) Kulpa with Lt. Stutz were all dispatched to the scene.

“Car was a 1964 Studebaker, 4 door sedan, tan in color, bearing W.Va. dealer plates DUC 5 609 which is issued to The Auto Ranch, North River Road, Wheeling. The car was in front of 336 Richland Avenue, which is the home of Paul Hankish. Mr. Hankish was in the car at the time of the explosion. On our arrival at the scene the fire department was attempting to remove Mr. Hankish from the front seat of the car. He was still conscious at the time.

“The car apparently was rocked by a terrific explosion. Both front doors were blown off the car, the entire front of the car which includes windshield, fire wall were blown off from the frame. The hood, fenders on the front, the grill, radiator, were off the car and scattered about the area. The yard across the street from the car at 339 Richland Avenue contained two large pieces which had been parts of the fenders; this is about 150 feet from the place where the explosion occurred.

“Other parts of the car were found all over the street. The right front fender was found in the back yard of the house at 408 Richland Avenue. It apparently had blown over top of the houses.”

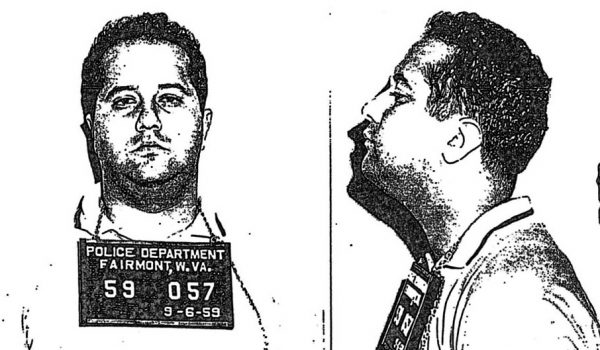

Someone tried to kill Paul Hankish, an impressive hustler who had spent time in prison for his involvement with stolen goods who was on probation at the time of the blast. The initial report (quoted above) was registered by Sgt. Jebbia and Det. Norton, and the filings that followed prove that local authorities and federal investigators agreed it was dynamite that ignited when Hankish attempted to start the on-loan automobile during this snowy morning.

The blast damaged seven homes along Richland Avenue, and several neighbors told police that they had heard the explosion. Along with the discovered debris mentioned in the above report, John Niebur of 340 Richland Ave. informed police that he had found a piece of the Studebaker’s hood on his house roof, and others in a nearby tree.

Only one man, though, witnessed the attempted murder. Harold Bauers of 346 Hazlett Ave. told police he actually saw the bombing take place. The report states he was on his way to get a haircut, and as he neared 4th and Richland Avenue he saw Hankish descending his front steps toward the street. He decided to stop and watch Hankish because he had heard the rumors about his criminal activity. Bauers told the authorities he saw the mobster get into his car, and then came the boom.

In the process of talking to Harold Bauers he stated the following: “When he ran over to the car to what had happened he seen Hankish in the front seat; he was conscious and said the words, ‘That fucking Bill Lias.’ Bauers then ran to call an ambulance.”

Open and shut case, right?

Wrong.

Wheeling officers Prezkop and Millard did have a chance to speak with the bombing victim later the same day, and he again implicated Lias, the “boss” of a mob network that involved gambling, prostitution, auto theft, and stolen goods.

“He said, ‘I’ll never change. F**k that fat pig.’ Millard asked who he meant and Hankish said Lias. When asked if it could have been anyone else from up the river around Youngstown or that area he said, ‘No. I get along with everybody but him.’

“Hankish at this time was still in pain but was coherent and his condition was good.”

Local investigators immediately began conducting interviews with known friends and associates in hopes of connecting Lias or anyone to the assassination attempt. Hankish’s first wife, Patricia, other family members, and his friends, though, all told the police they had no idea who could have perpetrated the bombing as Hankish never confided with any of them about his personal business. One after another said: “We never talked about his work.”

“That was the thing with Hankish. No talking, or he would take action,” said Tom Burgoyne, an FBI agent for 34 years who was not yet assigned to the Wheeling area at the time of the bombing. “And he did when people did talk, and people knew it. It was a pretty vicious atmosphere back in those days. If he had died in the bombing like he was expected to, it would have been interesting to see what people would have said then.

“I didn’t come to Wheeling until three years later, but I’ve seen the photos of the car and of the debris in the area, and who knows how Paul Hankish survived that,” he continued. “Someone definitely wanted him dead. You don’t do what these people did to just take his legs. Whoever really did it wanted his life to end.”

Mob-connected murders and attempted murders did take place in Wheeling, according to several sources, and the end goal after the lives were ended usually was to dispose of the evidence and of the body. The Ohio River, I’m told, was a popular depository, but so were local blast furnaces, coal mines, and concrete plants. Never were the bodies intact when taken to such places, and if a basement floor were the chosen destination, a visit to a butcher shop was part of the process.

On a few occasions when the remains of victims were discovered, the men were found without attached penises. Matters of the heart would get you killed much more quickly than debt or skimmed collections, and if a local man had relations with someone labeled off limits, his demise often was ugly.

But Paul Hankish, 32 years old at the time, did survive. He lost his legs, hence his nickname, “No Legs,” and the case file reveals there were aggressive attempts to discover his condition at Wheeling Hospital, and that several tips were offered to authorities during the days following the blast.

Det. C. Gilson filed this report that day after the murder attempt:

“At 9:00 a.m. this date (January 18) I was informed to see an Ann Thalman at 339 Richland Avenue by James Harkins in regard to a woman that said she had seen two men “fooling around a neighbor’s car” which was similar to the one bombed.

“At 9:15 a.m., I talked to Ann Thalman and she said to see her sister, Josephine Bauman, who informed me that the woman I should see was Ann Schmelick of 300 Richland Avenue.

At 9:45 a.m. I talked to Ann Schmelick and her husband. The only thing said by Ann Schmelick about the bombing was that she owned a 1964 Studebaker, 2 door, but not the same color as the one bombed. When she learned that a “Stud” had exploded she thought that it was the product and did not know that it was bombed. She said she was afraid to start her car thinking that it might blow up until she was told that the other car was bombed. At no time did she state that she saw two men ever fooling around her car or anyone’s car.”

Then during the evening of Jan. 18, Ptl. Reinbold was dispatched to Wheeling Hospital at 11:30 p.m. because staff members reported a suspicious man asking to see Paul Hankish. He was a good friend, he insisted, and he wanted to see him. This man wanted to know, for sure, whether Hankish was alive or dead. The hospital staff, according to the case file, did not reveal Hankish was a patient, let alone his official condition.

The telephone operator told police the next day someone with a similar voice continued to question Hankish’s presence and condition. This call was fielded by Paul Futey, an uncle to Hankish, the police report states. Futey told Hankish’s wife that the male caller could not have been a friend of Paul’s because of his age, and because of his aggressive behavior at the hospital. The caller was never told the information he wanted.

On Jan. 20, three days after the explosion, an unidentified man called the police department at 4:50 a.m. and said he could shed some light on the bombing. Of course, he did not wish to identify himself or get directly involved for fear of the same, but he did advise police to speak with a Patricia Warsham of Hildar. He said she could reveal a lot if she wanted, and promised to call again if Warsham did not cooperate. The file does not indicate the man ever called again, but Patricia Warsham later became the second “Patricia Hankish.”

And then on Jan. 21, 1964, with Hankish spending his fourth day hospitalized, Wheeling police officers Lt. Thomas and Sgt. Noll filed their report about their conversation with Bill Lias. At 10 p.m., they traveled to his residence on 15th St. in East Wheeling, and they asked him why his name might have been mentioned by Hankish.

“He told us that he and Hankish have not seen each other for approximately three years, this was before Hankish went to the penitentiary. He stated that he knew that Hankish was saying derogatory statements about him, but it made no difference to him. He said that if remarks bothered him, he would have been bothered his whole life.

“He was then told that Hankish had blamed him for the bomb and he said that this did not surprise him but that he had nothing whatsoever to do with it. He said that Hankish seemed to be jealous of him and that there had never been actual trouble between them and that Hankish certainly did not bother him enough by his remarks to even bother with him.

“We talked with Lias at some length with negative results.”

“Hankish was pretty young then, but he was making moves that were getting in on some of the action around town that until then was 100 percent under ‘Big Bill’s’ control. Hankish started snipping at it,” Burgoyne said. “No one ever proved that Bill Lias had anything to do with that bombing. But I can tell you what most people believed.”

Hankish was guarded by Wheeling Police on the top floor of the old Wheeling Hospital in North Wheeling. Det. John Mennillo chose to visit Hankish at 11 p.m. a few days after the incident. Hankish had just been sedated, but that did not stop Mennillo.

“I asked him several questions, and asked if he could help in any way to help the police in getting to the bottom of the bombing, and he told me to get my pencil and paper out and to write what he tells me. I told him not to make a fool out of me and he told me he wouldn’t, and for me to write. He stated the following: I HAVE ALWAYS GOT ALONG FINE WITH EVERYBODY IN WHEELING (which I did). Then he told me to cross out IN (which I did) then he told me to write Everywhere. He said to read that back to him, which I did. He continued: I HAVE NO ENEMIES THAT I KNOW OF. This I wrote; then I told him that it wasn’t any friend that did this to him.”

But then three weeks after having both his legs blown off, Hankish changed his story. On Feb. 6, 1964, Det. John Mennillo and Sheriff Tom Padden, the reports states, visited and Hankish offered a “No comment,” when asked if he knew who could have caused his injuries.

According to the report filed by Mennillo, “All he mentioned was that he had returned home around 1:00 a.m. and that he had gone to bed and arose the same morning to keep a personal appointment that he had made for 10:30 a.m. He said he left his home around 10:15 a.m. and got into his auto and the explosion occurred and he has no idea why or who committed the act.”

“By that time he was pretty sure he was going to survive without his legs,” Burgoyne said. “So he got smart. He shut up. He knew he had to make a living once he got out of the hospital, and whether or not he really thought Lias had something to do with it didn’t matter anymore.”

Pat Hankish, Paul’s first wife, altered her story, too. Initially she told investigating officers that her husband had returned home the night before the assassination attempt by midnight, but she “…voluntarily told us that the time element in her original statement could have been wrong. She told us that Paul called her Thursday evening and told her that he was going to be late, and she knew he was supposed to be home by midnight so she took it for granted that he called at approximately 11 p.m. She said she had neither a clock at her disposal nor had the radio or TV on and she was cleaning out a kitchen cupboard at the time he came in and she could not tell us what time it was. She said say they turned on the TV and watched the late movie on KDKA which comes on in the neighborhood of 1 a.m. She said she did not believe that Paul came home as late as 1:30 a.m.”

Just 30 hours after an estimated seven sticks of dynamite exploded a firewall away from Hankish’s toes, agents with the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrived in Wheeling and stayed at the Downtowner Motel on Main Street. Their focus, according to the case file, was the vehicle and determining how the bombing was perpetrated. The FBI also processed the collected evidence that included parts of the vehicle and the clothes worn by the ringleader at the time he turned the key.

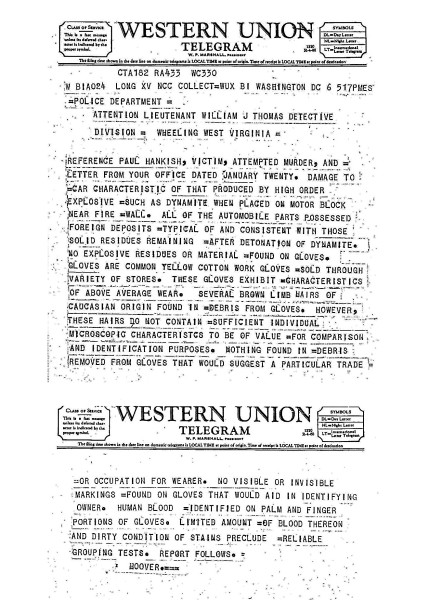

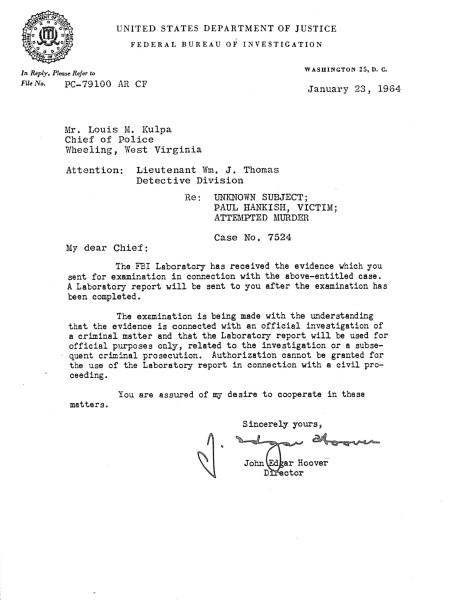

Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI in 1964, composed a letter to Kulpa on Jan. 23 confirming receipt of the evidence, and then he dispatched a Western Union Telegram to Det. William J. Thomas on Feb. 6 offering the bullet points of the findings. The next day the FBI returned its report to the Wheeling PD and confirmed the damage to the Studebaker was consistent with what would be produced by a “high-order explosive such as dynamite when placed in the rear of the engine block near the firewall.”

So local authorities officially knew what took Hankish’s legs thanks to science, but they still did not possess a solid clue as to who set the trap.

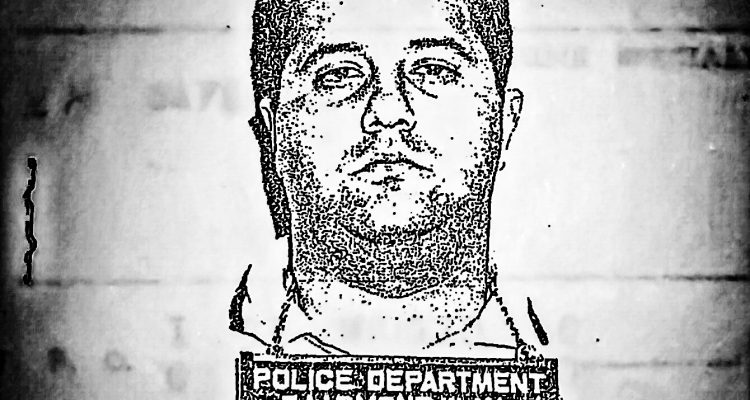

Investigators from the Wheeling Police Department tracked the victim’s travels through the W.Va. Parole Board, and Hankish’s on-the-record employment involved jewelry, automobile and plate glass sales throughout the tri-state region. He received permits to travel to cities in all three states like Martins Ferry and Bellaire, but also Philadelphia and Point Pleasant. The authorities also identified the individuals photographed by the police and media members while they lingered at the crime scene.

But, as it turned out, the bombing helped Hankish rule the mob world in the Wheeling area soon after he was released from the hospital. He was seen often in a wheelchair or wearing prosthesis while using crutches, and his survival was respected. He became so connected that at one point he was collecting income generated by two men who trained a monkey to crawl through the night depositories at local banks to swipe the moneybags.

“By the time I arrived to Wheeling in 1967, Paul Hankish was up and running, and he was in control of the number sheets and sports betting rackets, and he had taken over the prostitution, and he was into stolen property big time,” Burgoyne reported. “And by that time Bill Lias was pretty much out of it. The only time I ever heard the Lias name it was when people were talking about past activities. When I got here, it was all about Paul Hankish, and that was because he survived.

“Surviving the bombing gave him instant credibility and not just with the people in and around Wheeling. It gave him credibility all over the East Coast, and that allowed him to get involved with a lot of activity,” the former G-Man continued. “He bought a place down in Hallandale Beach that’s located a little above Miami, and a lot of the mobsters used to go there in the winter. The fact that he survived that bombing made him a conversation piece and opened a lot of doors for him. They called him, ‘Paul No Legs.’”

Burgoyne insisted that being a part of a team that finally put Hankish in federal prison in 1990 was not the most significant case in his federal career while he was assigned the Wheeling area.

“It was a big case, no doubt about it, but I just wish we could have gotten him when he was in his prime,” he said. “It was in 1986 when representatives of the FBI, the Wheeling Police Department, and even the IRS started meeting weekly in the federal prosecutor’s office so we knew what everyone was doing. That was the first time we all started working together, and that’s why when the indictments came down, there were so many from all directions. We all had him on a lot of different things because he didn’t care much about what was legal or illegal.

“He was very careful, though, when he was younger. Plus, he took himself out of the equation by going to Florida during the winter, and that’s when the people working for him were more careful than ever,” Burgoyne continued. “But then in the late 1980s he got sloppy. He got addicted to cocaine, and he lowered his guard.

“Paul Hankish was a young thug; that’s what he was before the bombing, and that’s why someone tried to kill him. He was moving around doing a lot of things, and someone didn’t like it. After his recovery he had a lot of good years, but when he died in prison, he had nothing.”

The case file was the subject of a lawsuit filed against the city of Wheeling in the late 1990s, and the municipality lost the Freedom of Information Act challenge in September 2010 when Circuit Court Judge Martin Gaughan ruled in favor of public access. Initially, Wheeling’s city solicitor Rose Humway-Warmuth objected to releasing the file because it remained unsolved at the time, but despite the fact the file’s contents have been reported on since, the case still does not include a conclusion.

“And it never will have an ending,” Burgoyne said. “I know what I was told after coming here, and the majority believes it was Lias because Hankish was running his mouth and stealing action back in those days. No one could prove it though, and unless someone comes back from the grave, no one ever will.”