Just about every school child knows the story of how a 17-year-old girl named Elizabeth Zane saved Fort Henry by running to the cabin of Ebenezer Zane and returning with an apron full of gunpowder amid a hail of musket balls and arrows from the British and Indian attackers. The story of her courageous gunpowder run was repeated many times and even made its way to the Virginia Legislature. Zane Grey made sure that it would endure by publishing a book about Betsy Zane in 1903. So much is written about Betsy Zane that the historical documents are full of contradictions. The purpose of this document is to try to sort out the best version of the truth about Elizabeth Zane.

Elizabeth Zane is best known as “Betty Zane.” However, she was actually called “Betsy” by her friends and family members, so she will be called “Betsy Zane” in this document to distinguish her from her sister-in-law, Elizabeth McCullough Zane, who was known as “Bessy Zane” by her friends.

Elizabeth (Betsy) Zane was born somewhere around what is now the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. Her actual place of birth is uncertain. Some historians place it at Moorefield Va. (Now W.Va.). We will leave the challenge of determining the exact location to others! Elizabeth Zane was the youngest of six children born to William Andrew Zane and his wife, Nancy Ann Nolan. She had five brothers: Silas (born 1745), Ebenezer (born 1747), Andrew (born 1749), Jonathan (born about 1750), and Isaac (born 1753) Historical documents disagree on Betsy’s date of birth. Some sources list it as July 19, 1759, and others list it as July 19, 1765. Our research supports the 1765 date. One good piece of evidence for that date was the fact that Betsy was in high school until 1881.

Not much is known about Betsy’s early life. At some point, she went to Philadelphia to live with her aunt so that she could go to school. Various sources describe her as thin and athletic with an independent spirit, an outgoing personality, and an attractive appearance. When her aunt died in 1781, she came to the Wheeling area and joined her brothers. By all accounts, Betsy immediately attracted the attention of the young men in the area. Most accounts describe a friendship between Betsy and Lydia Boggs, who was one year younger than Betsy. However, many historians also speculate that the two girls were rivals for the attention of the young men in the area and that Lydia may have resented Betsy for showing up and attracting the attention of those young men who were previously paying more attention to Lydia!

Betsy Zane would have faded unknown into history if she had not made the famous gunpowder run during the 1782 siege of Fort Henry, so here is that story. The story of the famous gunpowder run actually starts with the 1777 attack on Wheeling and Fort Henry by the Indians and British. Although the defenders of the fort were able to hold off the Indians and British in 1777, the attackers burned the cabins in Wheeling before they left the area. Ebenezer Zane declared that he would build a new cabin that he could defend and would not allow it to be burned again, so he constructed his new cabin in the form of a blockhouse. A blockhouse has an upper story that extends out and overhangs the lower story. The overhang provides an elevated shooting platform. In addition, the thick planking in the floor of the overhang is constructed so that the defenders can shoot through the cracks between the planks to take care of anyone who tries to get near to the cabin to set it afire. Adjoining the blockhouse on the south side, Zane built a summer kitchen which consisted of a small cabin between the blockhouse and the cornfield along Wheeling Creek. The front of Zane’s cabin faced Fort Henry, which was about 60 yards to the west, so the shooters in the cabin could cover the front of the fort and the fields on the north and south sides of the fort. Meantime, the shooters from the fort had a clear view of the front of Zane’s cabin and the north and south sides of the cabin and summer kitchen. So the cabin could only be attacked from the east. The summer kitchen and the cabin provided cover for each other for any attack from the east, so it was a very defensible design.

After the 1777 attack on Fort Henry, the Indians and British burned and destroyed everything in Wheeling except for what they were able to carry away with them. That included most of the cabins and other buildings. Things were tough, and Ebenezer Zane’s letters to Gen. Hand and Gov. Patrick Henry for aid did not bring much outside help. During 1778, some items from the fort vanished. Most of the residents suspected that the thief was Capt. Sam Mason who had been wounded at the beginning of the 1777 assault on the fort. Mason ran a tavern in the Fulton area and he had a reputation as a shady character in spite of his heroism during the Indian attack. Because of the attitude of the community toward him, Mason eventually moved his family to Washington County, Pa., but his is another story!

During the five years between 1777 and the next assault on the fort in 1782, Fort Henry was usually unoccupied and fell into somewhat of a state of disrepair. Various people commanded Fort Henry during that time. Between 1779 and 1781, Capt. Benjamin Biggs commanded the fort, but Biggs lived in West Liberty and seldom visited the fort. There was no full-time garrison at the fort. Ebenezer Zane sent a request to General Irvine at Fort Pitt requesting a supply of powder and lead to be kept at his cabin for the fort. Zane promised to be responsible for the powder and lead and stated in his letter that he would “personally account for any which is not expended at the enemy.” Since the fort was usually unoccupied, Zane kept the powder and lead at his cabin.

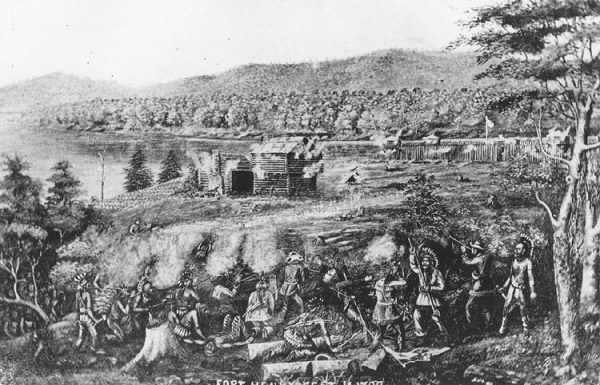

Lydia Boggs Shepherd Cruger described the fort as having a stockade made of squared vertical timbers fitted tightly together to form the outer wall. There were a barracks and a couple of other small buildings inside the fort. On an elevated platform atop the barracks building there was a swivel gun which was a small cannon, with a bore of about two inches, similar to those used on the railings of ships. Cruger also stated that the western end of the northern wall was in very bad shape by the time of the 1782 attack. That portion of the wall had been set on fire by the Indians during the 1777 attack on the fort. Lydia referred to the vertical posts as pickets. She stated that some of the pickets in the western portion of the north wall were completely rotted through creating a weakness in the wall. Had the Indians rushed up against the wall in that place, she believed that they could have knocked down a section of it. However, there was a peach orchard near the fort just north of that portion of the wall, so the damaged section was not visible to the Indians. Other eyewitnesses also support this description of the fort complete with the damaged pickets and the peach orchard on the north side.

The 1782 Attack on Fort Henry

The Wheeling inhabitants had very little advanced warning of the 1782 attack on Fort Henry. While scouting in Ohio on the morning of Sept. 11, 1782, a man by the name of John Lynn discovered a force of nearly 300 Indians accompanied by around 40 British rangers advancing toward Wheeling. He rushed to warn the inhabitants of the impending attack. After swimming the Ohio River to reach the town, he raised the alarm, and the residents rushed into the fort. Accounts differ regarding the number of defenders of the fort, but most historians agree that there were less than twenty men inside the fort along with 40-50 women and children. Ebenezer Zane and his wife, Elizabeth McCullough Zane (Known as Bessie), along with Andrew Scott and his wife, Molly Scott, and a friend named George Greer all rushed into Ebenezer Zane’s cabin about 60 yards east of the fort. In addition a black slave known as Daddy Sam along with his wife, Kate, took to the summer kitchen adjoining the cabin on the south side.

Accounts also differ in regard to who was in command of Fort Henry at the time. Some historians insist that Ebenezer Zane was in command of the fort, and others insist that it was commanded by Capt. John Boggs, who was the father of Lydia Boggs Shepherd Cruger. However, Ebenezer Zane chose to defend his cabin, and Capt. Boggs volunteered to ride to some of the nearby forts to seek reinforcements, so Silas Zane was in command inside the fort at the time of the attack. Among the inhabitants of the fort were Elizabeth Zane (Known as Betsy) and Lydia Boggs. The first attack on the fort took place on the evening of Sept. 11, 1782. Before attempting to storm the fort, the British Commander, Capt. Pratt, offered the Americans terms of surrender. After a brief discussion, the offer was refused, so the British and Indians attempted to storm the fort. There is good evidence that Simon Girty’s brother, George Girty, was leading the Indians.

Inside the fort, both men and women stood ready at the loopholes. Some of the women were expert shots. The assault was repulsed by deadly fire from the loopholes and from Zane’s cabin, which had a clear view of the front of the fort and of the fields on the north and south sides of the fort. The British and Indians had assumed that the swivel gun atop the barracks was a fake. However, they soon discovered that it was real. Eyewitness statements indicate that the swivel gun was fired a total of 19 times during the two-day siege. The swivel gun was loaded each time with a handful of musket balls which essentially turned it into an oversized shotgun. The psychological effect on the Indians was enormous and eventually contributed to the lifting of the siege. There is one account of a group of Indians taunting the occupants of the fort from a nearby house. The swivel gun was loaded with a ball and fired into the house. The ball must have hit a supporting beam or post because the roof collapsed into the house putting an end to the taunting.

Although the swivel gun was very effective, it also used a lot of gunpowder, so it soon became clear that the defenders of the fort would run out of powder. There was still a good supply of powder in Ebenezer Zane’s cabin, so the men decided that one of them would try to run to the cabin and return with the gunpowder. Seventeen- year-old Betsy Zane immediately declared that she was going to go because the men were needed to defend the fort. There are plenty of accounts of that conversation including Zane Grey’s fictional telling of the story, but Betsy had heard stories about what the Indians did to their young female captives. Many years later, she told one of her daughters that she had already decided that she would not allow them to capture her alive. She was also not as good with a rifle as most of the other women. There was actually not much discussion because Betsy had already removed her petticoats and other undergarments and was heading for the gate. Silas knew that Betsy did whatever she wanted to do, so he could not stop her anyway.

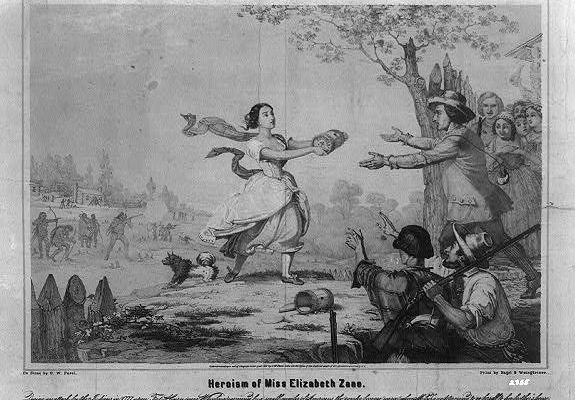

The gate was opened and Betsy sprinted toward Zane’s cabin. One of the British soldiers realized that it was a young girl and shouted out “a squaw, a squaw.” No one wanted to shoot an unarmed young girl, so not a shot was fired. There are lots of accounts about how Betsy carried the powder back to the fort. The one I like best goes this way: The women took one of Bessie Zane’s aprons, folded the bottom up and stitched up the sides to form a pouch. Then, they poured as much gunpowder into the pouch as they thought that Betsy could carry and then stitched the top shut. The amount of powder is uncertain, but it was probably an entire keg. (Remember that an apron back then was more like half a dress and included wide cloth straps that went over the shoulders.) Betsy put on the apron which was tied around her waist. She then took off on the run for the fort. She was over halfway to the fort before the surprised British and Indian attackers could react. By the time they opened fire, she was less than 100 feet from the fort. The musket balls skipping in the dirt kicked up dust which blew into her eyes making it difficult to see where she was going, but she managed to make it into the fort unhurt with the supply of gunpowder. Betsy’s gunpowder enabled the defenders to continue to use the swivel gun. Knowing that they could not take the fort and that reinforcements for the defense of the fort would likely soon arrive, the British and Indians broke off the attack two days later on Sept. 13.

The story of Elizabeth Zane’s heroics quickly spread and was even mentioned at the Virginia Legislature. It was unchallenged until 1849, when Lydia Boggs Shepherd Cruger claimed that it was actually Molly Scott who made the gunpowder run. Lydia said that Molly ran from the cabin to the fort, and she (Lydia) had personally poured the gunpowder into Molly’s apron to resupply the cabin which was about out of powder. She also said that the Indians were too far away to fire at Molly. In spite of Lydia’s statement, historians generally agree that Elizabeth Zane actually made the gunpowder run from the fort to the cabin and back. As mentioned previously, Ebenezer Zane requested the powder from Gen. Irvine and promised to keep it at his cabin and be responsible for it. Copies of that letter and a letter from Gen. Irvine at Fort Pitt to Gov. Patrick Henry detailing the locations of the powder magazines for the nearby forts are both in the Lymen Draper collection held by the Wisconsin Historical Society. Both letters place the gunpowder magazine for Fort Henry at the Zane cabin. In addition, Molly Scott’s daughter stated that her mother often told the story of Betsy Zane’s gunpowder run and of how it had saved the fort. Betsy’s own daughter said that her mom didn’t say much about it other than to mention that the musket balls kicked up dust which blew into her eyes making it difficult to see where she was going.

Betsy Zane’s Personal Life

Three years after the famous gunpowder exploit, Betsy Zane accidentally became pregnant. Her baby’s father was Van Swearingen. At the time, Betsy was either 19 or 20, and Van Swearingen was 43. Betsy expected Van to marry her, but Van had another girlfriend who was also pregnant. The other woman was Eleanor Virgin. Swearingen married Eleanor Virgin in May 1786 a month or so before her baby was born. The Zane family was very upset when they learned that Swearingen was not gong to marry Betsy, so they sued him for support for Betsy’s baby. The Ohio County Court in West Liberty ruled that Swearingen must deed over to Elizabeth Zane a piece of land that he owned in Ohio County to provide for the child so that he or she “would not become a burden on the county.” Swearingen complied with that order. The baby was a girl, and Betsy gave her the name of Minerva Catherine Zane She was also known as Miriam Zane. (Some historic documents refer to her as Minerva Catherine Swearingen, but there is no real evidence that her last name was ever Swearingen.)

Needing a husband and a father for her unborn baby, Betsy Zane married William Ephraim McLaughlin (usually known as simply Ephraim McLaughlin) in January 1786. Betsy Zane and Ephraim McLaughlin had four daughters together: Nancy Zane McLaughlin who was born July 12, 1788; Mary Ann McLaughlin, who was born April 2, 1790; Hannah McLaughlin, who was born Oct. 12, 1791; and Rebecca McLaughlin, who was born on an unknown date in 1797.

Betsy and Ephraim McLaughlin were married until his death in 1799. McLaughlin’s death was somewhat of a mystery. He went fishing on the Ohio River in a canoe. When he did not return home, searchers went out looking for him. They found his canoe, but no trace of Ephraim McLaughlin was ever found. He was assumed to have fallen out of the canoe and drowned.

The following year, Betsy again became pregnant. The father of her unborn child was Jacob Clark, who married her in 1800. The baby was a boy who was named Ebenezer Clark. Later, Betsy and Jacob Clark also had a daughter, whom they named Catherine Clark. Jacob and Betsy and their family lived in Ohio near St. Clairsville.

Elizabeth Zane McLaughlin Clark passed away on Aug. 24, 1823. She is buried at the Walnut Grove Cemetery in Martin’s Ferry, Ohio.

Elizabeth (Betsy) Zane memorial at Walnut Grove Cemetery in Martin’s Ferry

I hope that you have enjoyed this story. If you have studied the events in this story and determined that some of my information is flawed, I will defer to your expertise. I am not a historian, but I am instead a historical storyteller. I try not to allow the facts to interfere with a good story! – Earl