Wheeling has a long and rich history of prospering textile industries such as wool, tanneries, and dye works. Many of these companies have historically been owned and operated by men, with women being largely excluded from the workforce early on. So does this mean that the textile industry in Wheeling has always been a boy’s club? At first glance, the answer appears to be yes. However, if you dig a little deeper, it’s clear to see that women have certainly played a role in the success and continuation of the textile industry in Wheeling.

Wheeling’s Textile Industry

Some of Wheeling’s notable textile businesses throughout history were in operation during the mid to late 1800s, and some even into the 1900s. The shops consisted of Market Street Dye House, J. L. Stifel & Sons Calico Works, Wheeling Silk Manufactory, J. G. Hoffman and Sons Tannery, and Bradley and Eckhart Wool Mill.

Market Street Dye House was a company owned and run by A. Graham that specialized in dyeing fabric and clothing. The company was active during 1849, and offered services that included dyeing silks, satins, velvets, feathers, wool, and cotton goods. Men’s clothing could be sourced, re-dyed, and finished good as new and was warranted not to stain. Women’s clothing such as shawls, dresses, and kid gloves could also be cleaned, colored, and preserved.1

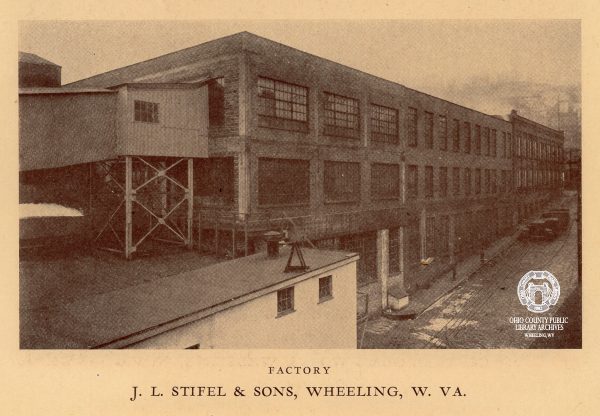

J. L. Stifel & Sons Calico Works was another dyeing and printing business in the area that was created and owned by Johann Ludwig Stifel and was in business between 1835 and 1957. The company dyed calico, which is an unbleached and undyed 100% cotton fabric.2 The business quickly took off and within a few generations went from one man and a small shop to “a 70,000 square foot plant, with many employees, which was shipping products like indigo-dyed prints internationally”.3 The process of dyeing the calico consisted of “singeing the cloth to remove fuzz and lint, boiling the cloth to remove waxes and oils, bleaching the cloth to remove natural colors, and dyeing the cloth with indigo extracts to give it the distinctive Stifel blue color”.4 The company was in business for 122 years but eventually faced financial and competition trouble after WWII and closed in 1957 before burning down in 1961.

Wheeling Silk Manufactory was owned by John W. Gill, and the company moved to Wheeling in 1845.4 Gill produced high-quality silk products that were said to be some of the finer silk fabrics in the United States.5 According to an article published in Scientific America in 1853, Gills products included “satins, velvets, dress silks, hat and coat plushes, brocades, vestings, levantines, surges, florentines, flag silks, handkerchiefs, scarfs, cravats, gloves, socks, shirts, sewing silks, coach lace, and trimmings, tassels, and twist buttons”.

J. G. Hoffman and Sons was a prominent tannery founded in 1849 by John G. Hoffman. The tannery produced heavy shoe-sole, harness leather, and high-quality hides that were sold throughout the country.6 The tannery started out small with only ten vats in 1849, but by 1852 the business had grown so much that they now had seventy-eight vats.7 The tannery was originally known as the Wheeling Tannery, but eventually became known as J. G. Hoffman and Sons around 1876.6

Bradley and Eckhart Wool Mill was in operation during the early 1860s and was one of the few businesses that had a woman owner. The wool mill was owned by Mrs. Elizabeth Bradley and John Eckhart, Jr. and the company produced flannels and jeans, as well as yarn for knitting and weaving. There were between thirty and forty employees, and half of them were women.7

Women and Wheeling Textile Industry

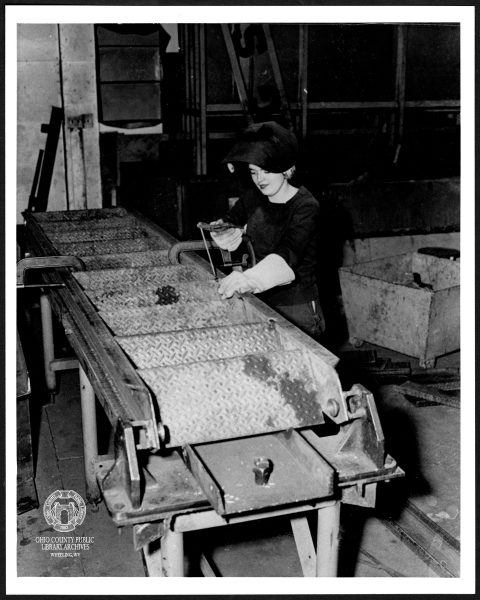

Before WWII most of the textile industry was largely male-dominated, along with many other industries in West Virginia such as coal mining, steel and lumber mills, and construction. Women who did work did work often did so out of necessity – the concept of paid employment for women at the time was more strongly linked to social identity than actual economic activity.

Women often could not find work and if they did, it was rarely in the mechanical, manufacturing, or mining industry. In fact, there was even a state law that made it illegal for a woman to seek work in the mines during 1887. Working women typically gravitated to industries that utilized their traditional domestic and nurturing skills – like sewing, weaving and canning. This made Wheeling’s textile industry a viable option for those seeking paid work.

The few women who did manage to find employment in this industry were typically paid very little, and what wages they did earn barely kept them fed. Many women had to work forty or more hours a week just to make ends meet during the Great Depression. Most were kept in the lowest earning category and made under a dollar per hour – sometimes making less than a thousand dollars a year.8

When WWII began and most men were drafted, many more job opportunities opened up for women to fill. The pay was still lacking, but there were women in many fields that previously had not allowed them. West Virginia Archives and History states that “nationwide, six and one-half million women were added to the civilian workforce… 94,689 women or 13.8 percent of West Virginia’s female population over the age of fourteen were employed. For the first time, the number of women employed in the iron and steel industry exceeded the number employed in the textile industry. The stone, clay and glass industry, which always offered some opportunities for women, now had a workforce that was 20.3 percent female.”9 However, the better-paying jobs in these fields that were considered dangerous and “less suitable” for women were still largely occupied by men.10

Women’s role in the textile industry has continued to evolve with the times. Today, women make up eighty percent of the textile industry10 and in the United States, women own over 21% of all textile, apparel, and accessories manufacturing businesses. 11 These strides have been made thanks to countless women whose individual stories are difficult to recount, and skills that have been passed down from generation to generation.

Women’s role in the textile industry and the legitimacy of “women’s work” is the inspiration for episode one of Weelunk’s latest podcast, Herstory. To take a deeper dive into the intersection of art and industry in the textile industry, listen to this week’s episode.

Herstory will continue with new episodes each Monday through March. Listen here on Weelunk, or wherever you get your podcasts.

References

1 “Market Street Dye House, 1849 .” Ohio County Public Library Digital Collection. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/2721.

2 Fabrics Galore. “A Complete Guide to Calico Fabric.” https://www.fabricsgalore.co.uk/blogs/fabric-news/a-complete-guide-to-calico-fabric#:~:text=Simply%20put%2C%20calico%20is%20a,cotton%27%20for%20the%20same%20reaso

3 “J. L. Stifel & Sons Calico Works.” Ohio County Public Library Digital Collection. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/2716#location

4 Ibid.

5 Scientific American. “A Western Silk Factory.” https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-western-silk-factory/

6 “Wheeling Silk Manufactory, 1849.” Ohio County Public Library Digital Collection. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/3027

7 Rotenstein, David S. “Tanneries.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 05 November 2010. Web. 04 March 2024.

8 “Tanneries of Wheeling, 1886.” Ohio County Public Library Digital Collection. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/3036

9 Ibid.

10 Hensley, Frances S. “Women in the Industrial Work Force in West Virginia, 1880-1945.” West Virginia History: A Journal of Regional Studies 49 (1990): 115-124.

11 Fairtrade International. “The Women Who Make Our Clothes Are Invisible. It’s Time to Change That.” https://www.fairtrade.net/news/the-women-who-make-our-clothes-are-invisible-its-time-to-change-that