When hotel clerk Howard Finley first saw Wheeling’s McLure not long after it re-opened in 1896 following renovations, he exclaimed, “Gee, ain’t she a whopper!” By that point, the donut-shaped structure had witnessed more than 40 years of history, including the completion of the B&O railroad in nearby Rosby’s Rock, the birth of the state of West Virginia, the fracturing of the nation during the Civil War and Lincoln’s “Emancipation Proclamation.”

Throughout those four decades, the status of the McLure as “the largest and finest hotel west of the [Appalachian] mountains” was well known by travelers from actors to politicians to military leaders. By the time Finley left the McLure to work as a traveling salesman for Wheeling’s Mail Pouch Tobacco in 1906, the hotel boasted more than 100 rooms, a spacious dining room, a bar and other amenities designed to make guests feel right at home.

In its nearly 170 year history, the McLure Hotel changed names and ownership multiple times. Even the original round structure eventually gave way to the modern design seen now at 1200 Market St. Nonetheless, for the majority of those years, the McLure served as a gathering place for decision makers (like Civil War General William Rosecrans), stage stars (like Jenny Lind) and America’s wealthiest families (like the Rockefellers).

Obviously, the old saying “if these walls could talk” is especially relevant when it comes to the McLure, and there is not enough space here to reveal all of her stories. So, today on President’s Day, revisiting the McLure’s presidential guest roster seems apt.

According to newspaper articles (no ledgers of the McLure remain), 11 U.S. presidents have spent the night at the hotel over the years. That list includes Chester A. Arthur, Teddy Roosevelt, William McKinley and others. Among these illustrious visitors, though, two stand out because of their impact on the city, the state and the nation.

WE LIKE IKE

Although President Dwight D. Eisenhower would eventually stay at the McLure, it was a missed speaking opportunity at the hotel that would bring national attention to Wheeling. California Sen. Richard Nixon was Eisenhower’s vice-presidential running mate for the 1952 election. Not long before the election, Nixon was accused of inappropriately taking money from supporters. The allegations did not blow over, and Eisenhower knew that if he had any chance of taking a seat in the Oval Office that he would have to either disavow Nixon and choose a different running mate or somehow convince voters that Nixon was an honest man.

On Sept. 23, 1952, Nixon gave what has become known as his “Checkers” speech in which he denied using campaign funds inappropriately. He acknowledged that he would do everything in his power to restore the confidence of the American people, but that he would not give back the black and white dog, who had been named Checkers by the Nixon children.

Despite the overwhelmingly positive response to this televised speech (which garnered the biggest audience in television history up to that point), Eisenhower was not quick to confirm that Nixon was still his running mate on the Republican ticket. Instead, he asked Nixon to meet him in Wheeling, W.Va., where he was headed for his next campaign stop. There, Eisenhower noted, they could discuss the next steps in their partnership.

When Nixon received word of Eisenhower’s request, he was livid. He felt that his well-received speech should be enough to satisfy Ike, and he refused to meet him in Wheeling. In fact, he attempted to resign from the Republican ticket, but reconsidered after supporters close to him persuaded him to make a deal with Eisenhower: Nixon would meet with him in Wheeling if the Republican National Committee agreed to allow him to remain on the ticket. An agreement was made and both men headed to Wheeling.

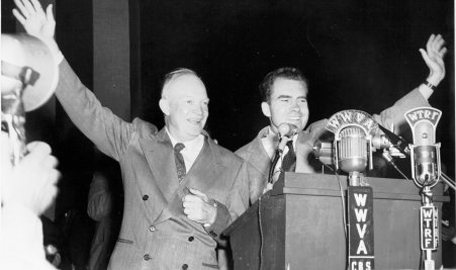

Unfortunately, all of the excitement prevented Eisenhower from making his scheduled speech at the McLure. After greeting a crowd of 3,000 at Stifel Field (Wheeling-Ohio County Airport), the two men and their families rushed off to Wheeling Island Stadium, where the men made speeches testifying to Nixon’s honesty and Eisenhower’s belief that his running mate had been wronged.

Eisenhower continued by saying, “Let there be no doubt about it, America has taken Richard Nixon to its heart, and the Republican party is proud to have Nixon on the ticket.” By the end of the joint speech, the crowd of more than 8,000 had become energized and buoyed by both men. Nixon concluded by saying that the rally at Wheeling Island Stadium was “the greatest moment of my life.”

TRUMAN AND BESS ACROSS THE U.S.

A few months later, the American people voted for Eisenhower and Nixon, who took Harry S. Truman and Alben W. Barkley’s posts in Washington D.C. Six months after Truman regained his civilian status, he and his wife Bess decided to take a 19-day road trip from their home in Missouri to the East Coast and back again. In those days, there was no secret service, and former presidents did not receive pensions, so Truman and his wife loaded their Chrysler New Yorker with 11 suitcases and attempted anonymity as they stopped at diners and hotels along the way.

Of course, they were rarely ever able to maintain their cover, and they were often thronged by local citizens and reporters excited to set eyes on the famous former first couple. When they pulled up to the McLure Hotel on June 20, 1953, the hotel clerk was surprised to see them. He called his manager who immediately set them up in a room on the fifth floor. This was not Truman’s first stay at the McLure. He had stayed there years earlier when he was a U.S. senator. In addition, he had given a speech not far from the McLure in October 1952. (To read more about that speech, visit Archiving Wheeling.)

Although the next morning he thwarted reporters’ questions about national issues, Truman told Dent Williams of The Intelligencer that Wheeling needs a flood wall and that he was sorry that the money needed for the wall was stripped from the federal budget. On his way out of town, Truman filled up his “shiny” Chrysler’s tank at a Wheeling gas station, and his attendant, Harry Spears, proudly smiles from the front page of the Wheeling News-Register in his uniform.

Although the next morning he thwarted reporters’ questions about national issues, Truman told Dent Williams of The Intelligencer that Wheeling needs a flood wall and that he was sorry that the money needed for the wall was stripped from the federal budget. On his way out of town, Truman filled up his “shiny” Chrysler’s tank at a Wheeling gas station, and his attendant, Harry Spears, proudly smiles from the front page of the Wheeling News-Register in his uniform.

PAINT THE WHOLE TOWN RED

It was also at the McLure just three years prior that Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy gave his now infamous “Enemies from Within Speech.” He was invited to speak at a celebration honoring Abraham Lincoln’s 141st birthday hosted by the Ohio County Republican Women’s Club. He roundly criticized then-president Truman’s foreign policies and questioned the loyalty of government officials.

Toward the end of his speech, he held up a piece of paper on which he claimed were written the names of 205 (later amended to 57 and 81) people “that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department.” This proclamation led to what soon after became known as McCarthyism. Although many people lost their jobs, no one in any government position was ever proven to be a Communist.

Years would pass, and President John F. Kennedy would find safe harbor within the walls of the McLure as would other famous figures, including his alleged mistress Marilyn Monroe. If the McLure’s walls really could talk I am sure they would tell us stories of sadness (at least one known suicide in the early 1900s), joy (Ethel Barrymore’s birthday party) and splendor (the Sweeney Punch Bowl being used at a society ball). In the end, though, I think she would keep her lips sealed because everyone likes a lady with a bit of mystery.

• Christina Fisanick, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English at California University of Pennsylvania, where she teaches expository writing, creative non-fiction and digital storytelling. She is the author of more than 30 books, including her most recent memoir, “The Optimistic Food Addict: Recovering from Binge Eating Disorder.” She has been a Weelunk contributing writer since 2015. Christina is a 1996 graduate of West Liberty University and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She lives in Wheeling with her family.