While Wheeling has a rich and proud history of organized labor, the issue and history of child labor is often overlooked. There are few records or histories examining or documenting child labor in Wheeling; the experiences, stories, and even names of the potentially hundreds of children who operated factories in Wheeling are lost to time…except for four photos by the famous photographer, Lewis Hine.

Children at Work

In the United States, child labor was an abusive yet common practice from the start of the Industrial Revolution until the Federal Labor Standards Act of 1938. Business owners often preferred child employees because their labor was cheaper than adults. In some cases, children were more suited to certain tasks in cramped factories, mills, or mines because of their smaller size.

In the 1870 US Census–the first census to report child labor statistics–approximately 750,000 children under the age of 15 were working.This statistic is staggering, considering Children working in family businesses or farms were not counted. Over forty years later, in 1911, over 2 million children under the age of 16 were working.1 While it is perfectly normal and acceptable today for children to work to earn extra money or supplement their family’s income–such as babysitting, working in a shop, odd jobs–child labor looked very different in the early 20th century. Many of those children worked full-time, they were responsible for significant portions of their family’s total income, and their jobs often came at the cost of much of their education.

Child Labor in Wheeling

Some of Wheeling’s most prominent citizens had their starts as child laborers. E. M. Statler, multi-millionaire and founder of the Statler Hotels chain, broke into the hotel business as a busboy at The McLure when he was 13–he had previously been hauling buckets of coal at a Bridgeport glass factory from the age of 9.2 Another Wheeling Hall of famer, Michael Joseph Owens, started out working at the Hobbs-Brockunier glass plant in Wheeling before the age of 15. Eventually, Owens’ mechanical inventions to automatize glass bottle production would be credited with eliminating the need for child labor in the glass industry.3 A newspaper review in 1908 even tried to put a positive spin on Wheeling’s child labor, commenting that “there is more than one factory president in Wheeling today who is prosperous, healthy, influential in the community and a good all-around citizen, who had to go into the factory when he was under 12 years of age.”4

However, while these are examples of child laborers who went on to become wildly prosperous, that kind of success was a rarity. At a meeting at the Wheeling Chamber of Commerce to discuss the proposed federal child labor amendment in 1925, Rabbi Nyman L. Iola described child labor as creating a “hopeless circle of poverty” where poor families “send their children to school for a few years, and then set them to work just as their own fathers had done them.”5

The Fight Against Child Labor

Child labor regulations and legislation were hot political topics in the first few decades of the 20th century in the US; they were often discussed in the same conversations as other labor reform legislation such as the 8-hour workday, factory regulations, fire escape laws, etc. While there was constant pressure to pass national legislation regarding child labor, most of the regulations and restrictions (or lack thereof) were passed by state and local governments during the late 19th and early 20th century.6 Starting in the early 1900s, West Virginia did pass legislation putting age limits on child labor during specific times, such as when school was in session for children under 14, but there was very limited enforcement. In fact, West Virginia’s child labor laws were more lax than that of neighboring Ohio or Pennsylvania–children on the border were known to cross into West Virginia to be able to work.

In addition to state and local legislation, there were federal child labor laws passed in 1916 and 1918, but they were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Two decades later during the Great Depression, various New Deal legislation did quite a bit to reduce and restrict child labor, including the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Public Contracts Act of 1936, and the Sugar Beet Act. Finally, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA) established minimum working ages of 14 (outside school hours) and 16 (during school hours) for any jobs.7 The FLSA–and its subsequent amendments–continues to be the primary legislation regulating child labor today.

A Famous Photographer Visits Wheeling

Lewis Hine, originally from Wisconsin, was a teacher turned photographer and investigator of child labor in the early 20th century. As a sociology teacher at the Ethical Cultural School in New York City, he began photographically documenting immigrants on Ellis Island and eventually produced photos for The Pittsburgh Survey, a sociological study on urban conditions in 1907-08. Hine’s photography caught the attention of the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), an agency that worked to bring attention to and advocate for child labor legislation. He started as a freelancer and eventually served as the NCLC’s official photographer from 1911 to 1916.8 Over the course of his tenure, Hine took thousands of photos of child laborers and working conditions. These photos are credited as one of the most impactful campaigns to end the exploitative systems of child labor in the United States.

In order to get access to the work sites to take photographs of child laborers and working conditions, Hine would often have to adopt a disguise, such as an industrial photographer or Bible salesman. Photos of young children and their often unsafe and unsanitary working conditions were circulated far and wide in the form of magazines, books, slide lectures, exhibitions, reports, pamphlets–anything to bring the injustices to the attention of government officials and the broader public. Hine often had the children look straight into the camera–straight into the viewers’ eyes.9

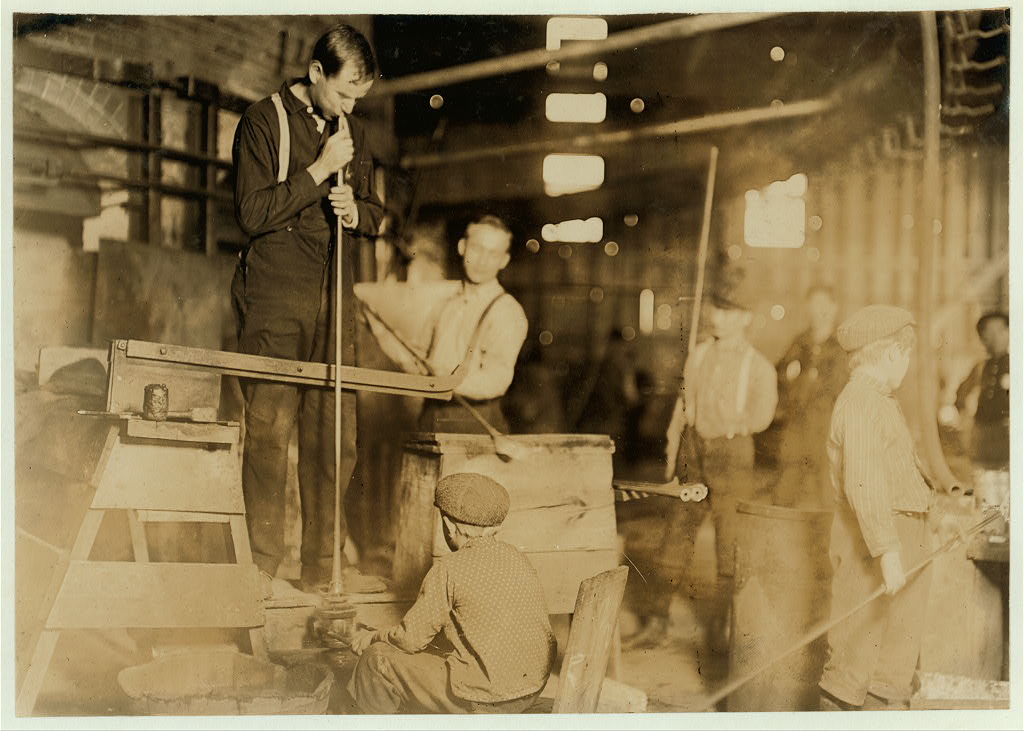

In October 1908, Lewis Hine traveled to Wheeling and took these photos of child laborers working in the Central Glass Company and Northwood Glass Company. Compared to some of Hine’s photos from other places, there is relatively little description that accompanies the Wheeling photos. However, there are remarks such as “dozens of small boys here” or “several very young girls pack here.” In many ways, the photographs hauntingly speak for themselves.

The Child Labor Debate in Wheeling

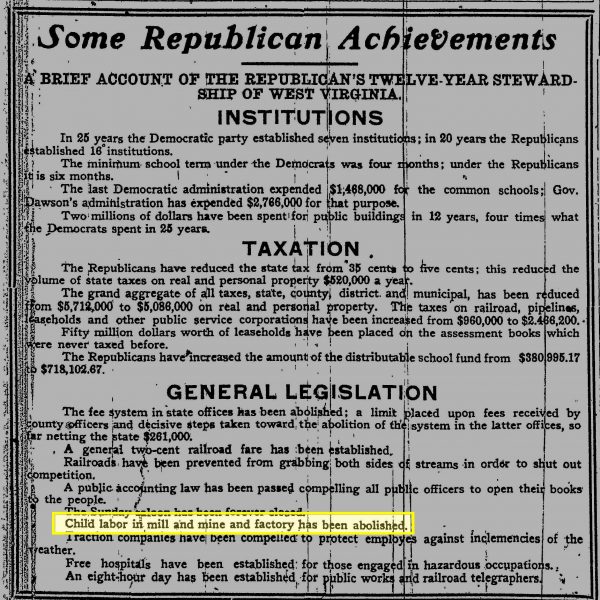

Being such a contested and political topic, the Wheeling Intelligencer reported widely on the question of child labor, both nationally and locally. The paper was largely skewed Republican during this time and reported in favor of Republican policies and actions regarding child labor. Under a list of Republican accomplishments on the front page on October 23rd, 1908, there is a claim that “Child labor in mill and mine and factory has been abolished.”10

Yet, it was in this same month that Lewis Hine took the photos of child laborers working in Wheeling factories.

Around this time, there were several active laws in West Virginia that attempted to curb child labor. For example, a compulsory education law required every child between 8 and 15 to attend school for at least 24 weeks a year–today, children attend 36 weeks–and another law prohibited children under 14 from working during the time school was in session.11 However, loopholes pushed children to work night shifts, weekends, and holidays, or flout the laws altogether. In one report on child labor in West Virginia, published the same year as Lewis Hine’s visit to Wheeling, children working the night shift at a glass factory were asked how they stayed awake, especially after attending school during the day. Their response: “We chew tobacco.”12

A month after Hine’s visit to take photos, E. N. Clopper, who was the secretary of the Ohio Valley States of the NCLC, showed photos of child labor in West Virginia to the Wheeling Board of Trade in his stereopticon–a type of slide projector that makes the photos appear to have a 3-dimensional quality.13 There is a possibility that the photos referenced were Hine’s photos from a month earlier–both were involved with the National Child Labor Committee at the time.

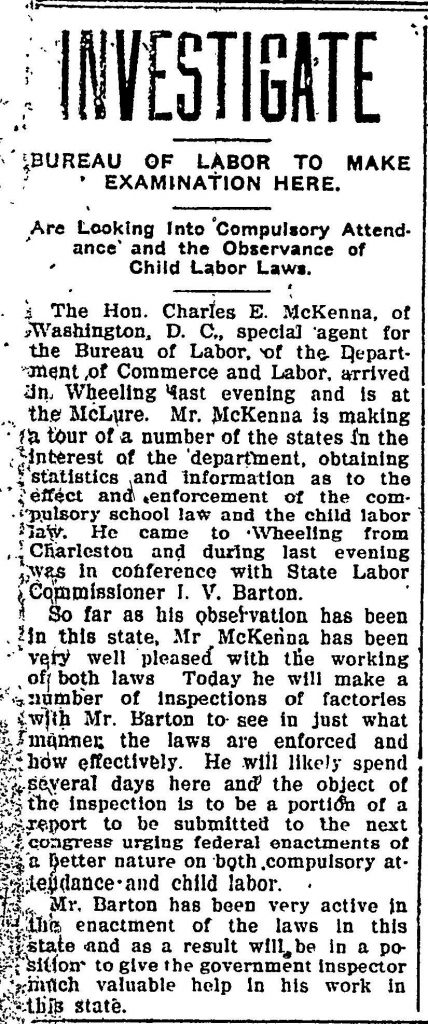

In fact, it was during this same time that the Bureau of Labor was inspecting Wheeling factories for enforcement of child labor and compulsory education laws. It was no secret–the arrival of Charles McKenna, special agent for the Bureau of Labor, and the reasons for his visit were publicly announced in the Wheeling Intelligencer.14 The investigation occurs at the end of October 1908 and it is unknown whether it is related to Hine’s visit; however, it is clear something was going on in Wheeling.

“Immediate and Profound” Impact

To have a photographer like Lewis Hine in Wheeling was historic…yet no one in Wheeling at the time knew he was actually here. While his work was often secret, the impact of his photos was “immediate and profound” in bringing serious awareness to and action against child labor in the US.15

Wheeling was part of that story, part of that impact. Wheeling’s history, identity, and character is steeped in its period of industrial labor, factories, and labor organizing. We just can’t forget that children and the issues of child labor are also part of that legacy.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 J. Hansan, “The American Era of Child Labor,” VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project, 2011, accessed December 4, 2020, https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/child-welfarechild-labor/child-labor/

2 “Wheeling Hall of Fame: Ellsworth Milton Statler,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed January 14, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/wheeling-hall-of-fame-ellsworth-milton-statler/4160.

3 “Wheeling Hall of Fame: Michael J. Owens,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed January 14, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/wheeling-hall-of-fame-michael-j.-owens/5183.

4 “Child Labor,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, December 9, 1908, p. 4, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22child%20labor%22&i=f&by=1908&bdd=1900&bm=12&bd=11&d=12111908-12111908&m=between&ord=k1&fn=wheeling_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19081211_english_4&df=1&dt=1

5 “Debate Proposed Constitutional Child Labor Amendment,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, February 4, 1925, p. 6, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22child%20labor%22&i=f&d=01011900-12311950&m=between&ord=k1&fn=wheeling_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19250204_english_6&df=1&dt=10

6 Hansan, “The American Era of Child Labor.”

7 Hansan, “The American Era of Child Labor.”

8 “Lewis Wickes Hine,” International Center of Photography, accessed December 4, 2020, https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/lewis-wickes-hine?all/all/all/all/0

9 “Lewis Hine 1874-1940,” International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum, accessed December 4, 2020, https://iphf.org/inductees/lewis-hine/.

10 “Some Republican Achievements,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, October 23, 1908, p. 1, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22child%20labor%22&i=f&by=1908&bdd=1900&bm=10&bd=23&d=10231908-10231908&m=between&ord=k1&fn=wheeling_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19081023_english_1&df=1&dt=3

11 E.N. Clopper, “Child Labor in West Virginia: Pamphlet No. 86,” National Child Labor Committee: 1908, accessed November 9, 2020, http://www.wvculture.org/history/labor/childlabor05.html

12 Ibid.

13 “The Civic Club,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, November 30, 1908, p. 8, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22child%20labor%22&i=f&by=1908&bdd=1900&bm=11&bd=30&d=11301908-11301908&m=between&ord=k1&fn=wheeling_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19081130_english_8&df=1&dt=1

14 “Investigate: Bureau of Labor to Make Examination Here,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, October 22, 1908, p. 12, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22child%20labor%22&i=f&by=1908&bdd=1900&bm=10&bd=22&d=10221908-10221908&m=between&ord=k1&fn=wheeling_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19081022_english_12&df=1&dt=1

15 “Lewis Hine 1874-1940,” International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum, accessed December 4, 2020, https://iphf.org/inductees/lewis-hine/.