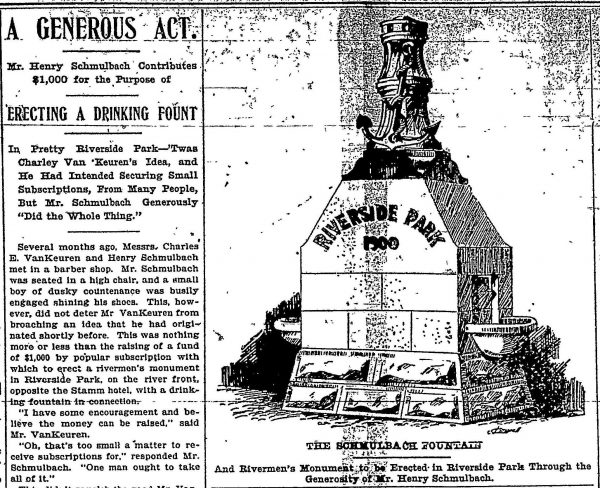

There is a secret hiding among the monuments at Heritage Port. Discerning eyes may have noticed that the Riverside Park monument has two half-bowl reservoirs on each side. Looking closer, one will see the metal drain fittings at the bottom of each basin. At its dedication in 1900, it was touted not just as a handsome tribute to Rivermen– those who derived their livelihoods from working on the Ohio River, but also as a public drinking fountain. If that sounds like a weird feature to include in a monument, read on, and let the past be a surprise.

“A short time ago, Mr. Charles E. Van Keuren conceived the idea of a drinking fountain to further beautify this pretty little park, and thanks to the philanthropy of one of our foremost citizens [Henry Schmulbach], who stopped Mr. Van Keuren then and there by giving him all the money for this beautiful monument and fountain.” 1

When Charles E. Van Keuren dreamed up the fountain for Riverside Park; the idea of public drinking fountains was not a new concept. Philadelphia, New York, and London were all providing safe, clean water to the public via fountains by the mid-1800s.2 These fountains were supported by a variety of stakeholders, from animal-rights activist groups (concerned with the draft animals being used to pull carts),3 to temperance boosters who thought increased access to drinking water would discourage alcohol consumption.4

The dedication for the Riverside Park Monument– or Schmulbach fountain as it was sometimes called, was quite the affair. On the evening of May 25, 1900, a procession of Mayer’s Brass Band and carriages containing Mr. Van Keuren, Congressman B.B. Dovener, Mayor A.T. Sweeny, master of ceremonies Mr. Charles J. Schuck, and Mr. Frank W. Nesbitt left from in front of the McLure hotel and proceeded to Riverside Park. Around roughly 7:30 p.m., the ceremonies began, with each of these men addressing the crowd. The monument, which was draped in a large American flag, was unveiled while the band played on. Mr. Nesbitt’s lengthy address ended on a point that pokes at the hard-working ethos of Wheeling:

“Let us turn from self-congratulation to self-examination. In our rapid strides toward material success we have been guilty of one grave folly. When tired humanity has finished [their] day’s work, [they] put on the best [they] have and goes forth to mental and physical recreation and rest. But how is it with our city? Our working clothes are all we have; we have no holiday attire. Where are our monuments and memorials? Where are our grassy plots and breathing spots? Where are our city commons?” 5

After Nesbitt’s address concluded, the water supply to the fountain was turned on, and those gathered took turns sampling the running water. Riverside Park remained a “grassy plot” for Wheeling to enjoy their leisure time but eventually was turned into the memorable Wharf Parking Garage. Around this time, the monument was moved to 29th Street and then moved again to the Wheeling Island Marina.6 Because change is the only constant in life, the Wharf Parking Garage met its demise in 1998 to make way for Heritage Port, reconnecting downtown Wheeling with the riverfront.

Still not quite sure where the Riverside Park Monument is? It’s one of the artworks featured on the Wheeling Public Art Trail. Check out all of Wheeling’s monuments and other public art by visiting wheelingheritage.org/public-art-trail.

References

1 The Wheeling Intelligencer, May 25, 1900

2 Josselyn Ivanov, “Drinking Fountains: the past and future of public free water in the United States” Thesis: M.C.P., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, 2015. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/99098

3 Ashley Hahn, “Curbside refreshment for man and beast” WHYY, May 29, 2013 https://whyy.org/articles/curbside-refreshment-for-man-and-beast/

4 Ivanov

5 The Wheeling Intelligencer, May 25, 1900

6 The Wheeling Intelligencer, July 24, 2003

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.