For many a West Virginian, the story of Zona Heaster Shue — better known as the Greenbrier Ghost — is a familiar one. The small details may differ, but the story usually goes something like this: in 1897, a recently wed woman named Zona Heaster Shue is discovered dead in her home by a neighbor. Zona’s husband, a blacksmith named Edward Shue, and a physician are called to the scene. The widower is wild with grief and will not allow anyone near his wife’s body, including the doctor. After a perfunctory examination, the doctor declares cause of death to be an “everlasting faint,” childbirth complications or a heart attack. Shue prepares his wife’s body for burial, and Zona’s kin are informed of her death. Upon hearing the news, Zona’s mother Mary exclaims, “That devil has killed her!” As the only one who suspects foul play, Mary is ignored — at first.

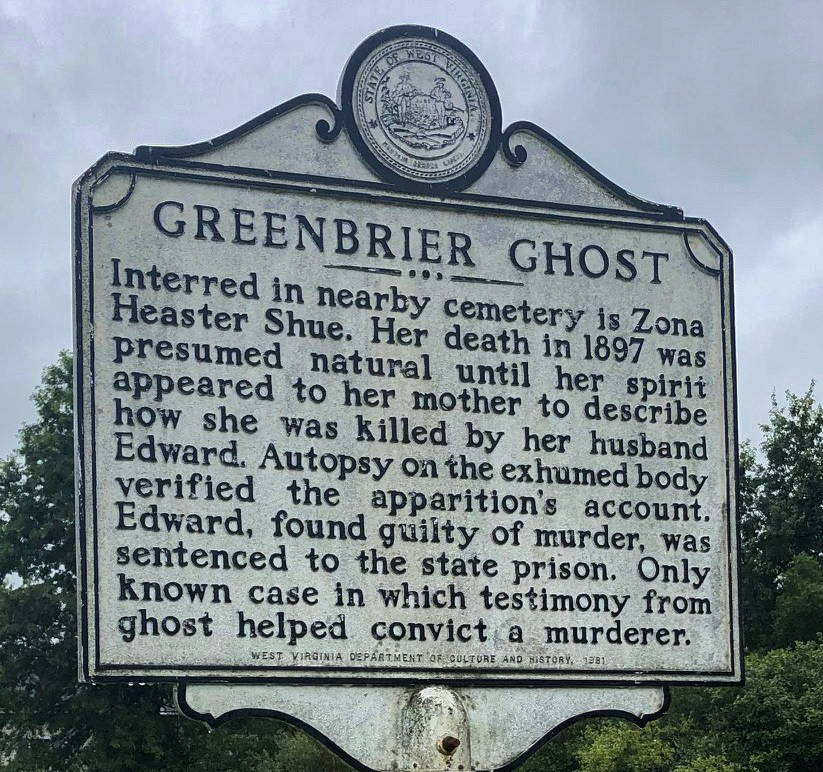

Shortly after her death, Zona appears to her mother and tells her she was murdered by her husband. Zona visits her mother four times, and on one visit turns her head completely around to show that Shue had broken her neck. Her mother takes her story to an attorney named John Alfred Preston, who orders that Zona’s body be exhumed and re-examined. Sure enough, the attending physicians find her neck has been broken, with telltale bruising to suggest strangulation. Her husband is put on trial and found guilty, making Shue’s the “only known case in which testimony from a ghost helped convict a murderer.”

A sensational story to be sure, and no doubt embellished in multiple retellings. So how does a reader separate fact from fiction? One might begin with a well-researched and gripping retelling like Sharyn McCrumb’s novel The Unquiet Grave. McCrumb breathes new life into an old legend and takes individuals who are often portrayed in folklore as one-dimensional and transforms them into real people with flaws, dignity and intelligence. Among the characters are Zona’s mother, Mary Jane Heaster, who is portrayed not as a backwoods busybody but as a grieving mother seeking justice. Mary Jane is intelligent and resolute, unwavering in her testimony even as prosecutors urge her to admit her “visits” from Zona were merely dreams. McCrumb also fleshes out a character who is often peripheral in the tale of the Greenbrier Ghost: James P.D. Gardner, one of the attorneys on Shue’s defense team and the first Black attorney to practice in the Greenbrier Court.

The story largely centers around Mary Jane and James Gardner, and though their stories occur in different times and places, the two narrative threads are woven closer and closer together throughout the novel and merge for the story’s culmination, the trial of Edward Shue. Mary Jane’s narrative takes place in Greenbrier in 1897 and follows a logical trajectory by beginning with Zona and Edward Shue’s courtship and ending after Shue’s trial. Gardner’s thread jumps around a bit more, sometimes set in the “present” during his stay at the Lakin State Hospital for the Colored Insane in 1930 and other times coinciding with Mary Jane’s as he recounts the events of Shue’s trial.

This is where McCrumb excels as a researcher and storyteller: not only does she expand the often one-dimensional Mary Jane Heaster, but she inspires the reader to become invested in the story of an otherwise minor character. In James Gardner, McCrumb rightly identifies a figure worth delving into. Gardner was an African American lawyer practicing in West Virginia only a few decades after the Civil War, and who served on the defense team for a white man accused of murder beside. The fact that Gardner would later be committed to an insane asylum is quite unexpected, which makes a reader wonder why Gardner’s story has not been given the spotlight before. McCrumb applies the same care to Gardner’s story as she does to Mary Jane’s and portrays him not as a man disconnected from reality but one who is too entrenched in it, which drives him to attempt suicide and leads him to Lakin.

One burning question McCrumb puts in the reader’s mind is whether or not Mary Jane Heaster did in fact see her daughter’s ghost or if the story was concocted to bring Shue to justice. No amount of research on McCrumb’s part could provide a conclusive answer, as the truth was buried a long time ago with the Heasters. Skeptics may put more weight in a woman’s intuition and assume Mary Jane conjured the ghost to support her hunch. Those who believe in the spirit realm may be inclined to believe the story of ghostly visitation and believe that, regardless of intuition, Mary Jane couldn’t have possibly known Zona was strangled. McCrumb tiptoes this line to the very end, only giving her interpretation in the final chapter. For McCrumb’s interpretation, and for a well-researched and engaging piece of historical fiction, readers are encouraged to read the book.

The story of the Greenbrier Ghost is ripe for the retelling, and many folklorists, historians, and paranormal investigators have given it due attention both before and after McCrumb. What sets The Unquiet Grave apart is McCrumb’s desire to recount the truth as best as one can, with respect for the parties involved and without sensationalism. Seeing the story treated as fact rather than folklore actually makes the story more engaging. In this instance, there is no need for embellishment to make a captivating story; instead, the tale of the Greenbrier Ghost serves as a perfect example of truth being stranger than fiction.

The Unquiet Grave is well-suited for fans of other historical fiction of the true crime variety, such as Jayne Anne Phillips’ novel A Quiet Dell and Emma Copley Eisenberg’s The Third Rainbow Girl: The Long Life of a Double Murder in Appalachia. I would also recommend it for anyone missing this year’s Mothman Festival who still wants their yearly dose of West Virginia-brand spookiness.

• Raised in Wellsburg, West Virginia, Anna Cipoletti is a proud alumna of Mount de Chantal Visitation Academy, West Liberty University and Kent State University. She received a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from West Liberty in 2014 and a Master of Library and Information Science degree from Kent State in 2017. Anna has made a career out of a lifelong love of books and works full-time at Bethany College as a librarian and parttime as a bookseller and book reviewer. She resides in Beech Bottom with her sister and two Siamese cats. A nature enthusiast, Anna often spends her free time visiting one of West Virginia’s many beautiful parks or kayaking along Buffalo Creek.