Editor’s note: At Weelunk, we’re all about keeping you connected to your community. Because that looks a little different right now, we’re bringing you ways to engage while staying safe and healthy. We hope Weelunk can continue to connect you to Wheeling — no matter where you are.

Are you up for a scavenger challenge?

This is a scavenger hunt for you to complete using Google Earth. The next few paragraphs describe some of the Wheeling area landmarks. Those descriptions include photos of those landmarks. After you read all of the descriptions, you will find a list of GPS (latitude and longitude) coordinates.

Your challenge is to find out which landmark goes with each set of coordinates using the Google Earth Street View. After you have completed searching for all of the landmarks, click the link provided to take an online quiz to see if you got them right.

Have fun!

By the way, the order in which the descriptions of the landmarks are given below is not the same as the order in which the GPS coordinates are listed for the challenge. That would make this way too easy.

Here are the descriptions of the landmarks for this challenge:

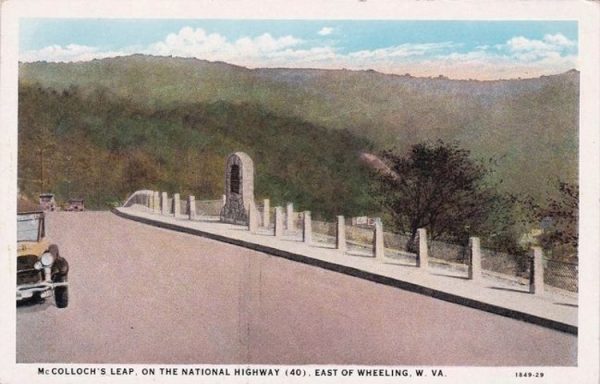

McCullough’s Leap

As you travel U.S. 40 near the top of the hill at North Park, you are greeted by a bronze statue of a Mingo Indian with his arm outstretched welcoming visitors to our area. The statue marks the place where Major Sam McCullough’s made his famous leap, which took place on Sept. 1, 1777.

McCullough was in command of Fort VanMeter in West Liberty when he received word that Fort Henry was under attack. McCullough quickly assembled a force of armed men and rode to assist the defenders of Fort Henry. McCullough’s actions took on added urgency because he knew that his sister, Elizabeth, who was married to Ebenezer Zane, was one of those fighting for her life at Fort Henry.

The 1890 History of the Upper Ohio Valley says that McCullough rode to Wheeling “at the head of 45 well-mounted men.” When a lull in the fighting occurred, McCullough’s men made a dash for the fort. Concerned first for the safety of his men, McCullough, followed at the rear of the group. The Indians recognized him at once and headed in pursuit of him thereby cutting him off from his men and denying him the ability to reach the fort.

As he rode up the hill with the Indians in pursuit, McCullough drew them away from his men who were able to reach the fort. When he neared the top of the hill, McCullough found his escape blocked by another group of Indians who were approaching from the other direction.

The Indians hated him, so they wanted to capture him alive so that they could torture him. Trapped between the two Indian forces, McCullough wheeled his horse over the side of the nearly vertical precipice. Horse and rider crashed down almost 300 feet through briars and undergrowth into Wheeling Creek below. Although scratched and bruised by the ordeal, both horse and rider survived the fall, and McCullough was able to make his escape. The Fort Henry defenders weathered the attack although the Indians and their British allies burned most of the town.

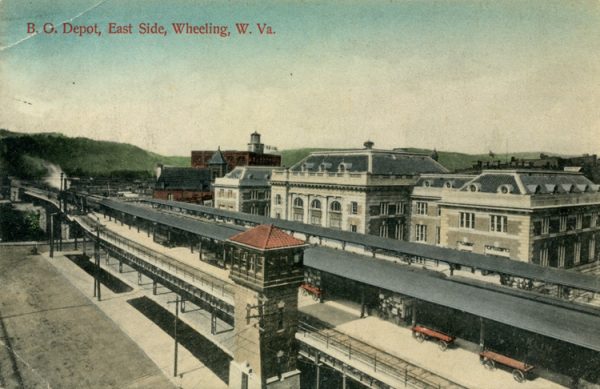

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Passenger Train Station

The Baltimore and Ohio Passenger Train Station, known today as the B&O Building, serves as the home of West Virginia Northern Community College. It is one of our most important historical landmarks. Construction on the train station began in 1906.

However, the flood of 1907 put a halt to the construction work, so the building was not opened to the public until Sept. 3, 1908. As passengers entered the building, they were struck by the extravagant interior from the marble floors and brass fixtures to the stained-glass dome overhead glowing from light provided through the skylight above.

After purchasing their tickets, passengers could take the elegant staircase or one of the elevators to the second floor where they would go out onto the platform at the rear of the building to board their train that arrived on an elevated trestle safely above any floodwaters.

While they were waiting, passengers enjoyed a bright interior lit by electric lights. During the winter, steam heat kept the building warm. The last passenger train pulled out of Wheeling in 1962. After being bought and sold a couple of times, the building was purchased by the state of West Virginia and became the home of West Virginia Northern Community College. For a more complete history of the B&O Building, visit The WVNCC Alumni B&O history page by clicking this link.

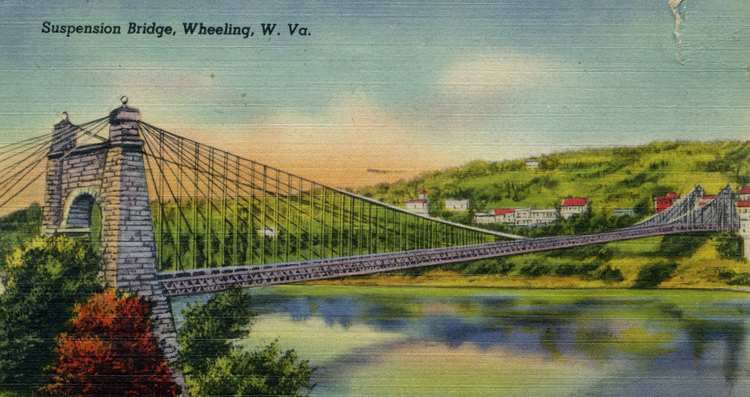

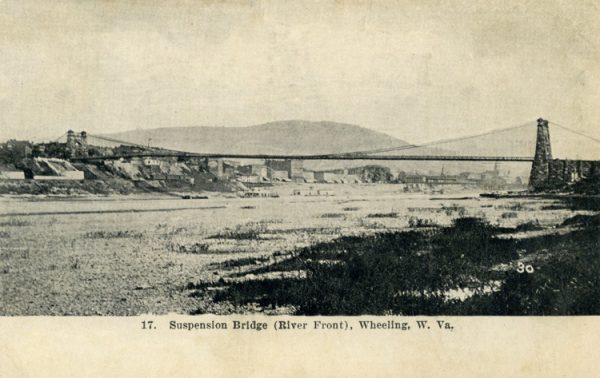

The Wheeling Suspension Bridge

In October 1849, with a huge crowd gathered on both shores and flags waving atop the towers, designing engineer Charles Ellet Jr. became the first to drive across the Wheeling Suspension Bridge. When his carriage arrived at the Wheeling Island shore, the roar of cannons celebrated the impending opening of the new bridge. That formal opening took place on Nov. 15 of the same year.

To help celebrate the opening, workers hung 1,000 oil lamps from the cables on the bridge creating a spectacle that the hundreds of witnesses would remember for the rest of their lives. Spanning 1,010 feet from tower to tower, the Wheeling Suspension Bridge became the longest toll bridge in America. It held that honor until May 24, 1883, when the Brooklyn Bridge across the East River in New York City opened with a span of 1,595.5 feet.

The Wheeling Bridge Company set the initial tolls for a round trip over the bridge at a nickel for a man or woman on foot, a dime for a man or woman on horseback, and 75 cents for a six-horse freight wagon. Although the tolls were slightly higher than those charged by the ferries, the bridge soon filled with traffic. In 1854, violent gale-force winds did major damage to the bridge, but it was quickly repaired and reopened in January of 1856. One hundred years later, on May 20, 1956, the Wheeling Suspension Bridge was dedicated as a national monument. The bridge is currently closed to vehicle traffic.

The Madonna of the Trail Monument

Located beside National Road not far from the entrance to Wheeling Park, the Madonna of the Trail monument is one of 12 identical Madonna of the Trail monuments, along the old National Trail, erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution and dedicated in 1928 and 1929. The 12 monuments recognize the hardships and sacrifices made by the women who traveled the Old National Trails Road on their way west.

Today, the portion of the Old National Trails Road east of the Rocky Mountains is known as U.S. 40. The DAR formed the Old National Trails Committee and gave it the task of coming up with a design for the monuments. In 1927, the committee approved a design by sculptor August Leimbach of St. Louis, Missouri. Later that same year, judge and later president Harry S. Truman, who chaired the committee, presented the approved design to the SAR. Truman assured the committee members and the SAR members that he would guarantee the funding for the monuments. Leimbach completed the first of the statues by the next year and the remainder by the following year. The SAR dedicated each of them as they were completed and placed along the road.

The design consists of a pioneer woman with a baby in her left arm and a toddler clinging to her skirt as she walks along clasping a rifle in her right hand. Speaking at the dedication of the Madonna of the Trail monument in Springfield, Ohio, future president Truman made these comments: “They (the women) were just as brave or braver than their men because, in many cases, they went with sad hearts and trembling bodies. They went, however, and endured every hardship that befalls a pioneer.”

Shepherd Hall (Monument Place)

When John Lynn swam the river to Zanesburg and raised the alarm, the inhabitants of the town rushed into the fort. Ebenezer Zane and his wife Elizabeth McCullough Zane (known as Bessie) along with Andrew Scott and his wife Molly Scott and a friend named George Greer all rushed into Ebenezer Zane’s cabin about 60 yards east of the fort.

In addition, a black slave known as Daddy Sam along with his wife, Kate, took to the summer kitchen adjoining the Zane cabin on the south side. Captain Zane left Lydia’s father, Captain John Boggs, in command of Fort Henry.

When the combined force of 300 British and Indians attacked the fort, 18-year-old Lydia stood beside the men and fought to defend the fort. Having grown up on the frontier, she was an expert marksman. When she was not firing from one of the loopholes, she assisted the other women by molding bullets and carrying powder and supplies to the men.

During the siege, she especially caught the eye of 21-year-old Moses Shepherd who was also defending the fort. Moses was the son of Colonel David Shepherd of Shepherds Fort, which stood near to the location of the McDonald’s in Elm Grove. The following year, the couple was married.

In the late 1790s, Colonel Moses Shepherd commissioned the construction of a stone mansion house for his wife. A virtual Who’s Who of society attended the 1798 dedication of Shepherd Hall. During the following years, the Shepherds became increasingly wealthy, and dignitaries from all over enjoyed their hospitality. U.S. Sen. Henry Clay visited frequently.

Because of his influence, the National Road route was altered to take it past Shepherd Hall. Colonel Shepherd also obtained contracts to build some of the bridges on National Road including the Stone Bridge over Little Wheeling Creek in Elm Grove. To show their appreciation to Clay, the Shepherds erected a statue of him near their home.

Colonel Shepherd became ill and died on April 29, 1832, when a cholera epidemic swept through the region. At the time of his death, he and Lydia had been married for 49 years. The following year, Lydia married New York congressman Daniel Cruger whom she had met during some of the many trips that she and her husband had made back east. Out of respect for her new husband, Lydia changed the name of the house from “Shepherd Hall” to “Stone Mansion.”

Daniel Cruger died suddenly on July 12, 1843, at the age of 62. Lydia never remarried and continued to live in the home until her death in 1867. Because of the statue of Henry Clay, Stone Mansion gradually became known as “Monument Place” which is how we know it today.

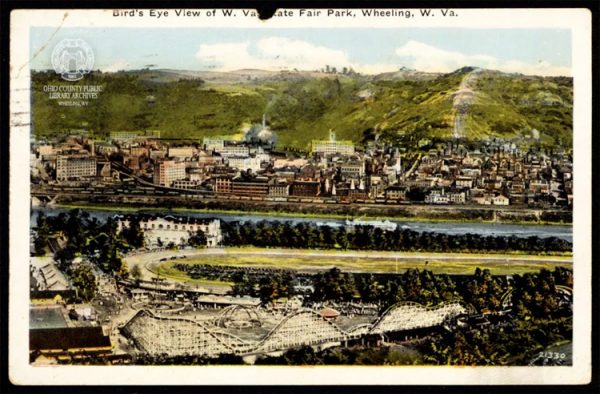

The Wheeling Island State Fairgrounds Exposition Hall (Wheeling Island Roller Rink)

During the mid-1800s, both ends of Wheeling Island attracted visitors for various fairs and festivals. Belle Isle Beach on the north end of the Island extended well out into the river providing plenty of bathing area. Concession stands sold snacks and drinks.

The fairgrounds on the south end of the island hosted a variety of events well into the early 20th century. The first event described as a fair took place on the south end of Wheeling Island on Oct. 9-12, 1866. The event became known as the Annual Fair & Stock Exhibition.

In 1881, the newly formed West Virginia State Fair Association purchased 25 acres of land at the south point of Wheeling Island to be used as a state fairgrounds. The first West Virginia State Fair took place at the site on Oct. 10-15, 1881. West Virginia Exposition and State Fair Association commissioned Wheeling architect Frederick F. Faris to design an Exposition Hall for the fairgrounds. Builders completed the construction in 1924 in time for the fair during the fall of that year. The new building measured 80 feet wide by 260 feet long.

After the 1924 fair, the State Fair Association opened the building to the public as a roller skating rink and it continued to function in that capacity until 1944 when the Hoover Sweeper company leased the building and converted it into a factory to produce materials to support the war effort.

In 1946, the Hoover Company removed the machinery and the old Exposition Hall reopened as the Wheeling Downs Roller Rink.

It continued operations under that name and the name, Milam Roller Rink, until 1980 when the building was closed for major renovations. The building reopened under the name, Wheelin’ Around. Wheeling Island Hotel-Racetrack-Casino acquired the building a few years ago and used it as a storage facility until it was destroyed by fire on New Year’s Eve of 2019.

Your Challenge

If you choose to accept the challenge, copy and paste each set of coordinates given below into the search box on Google Earth. Then, use Google Earth Street View to look around for the landmark. On a piece of paper, list the numbers 1 through 6. As you check out each set of coordinates using Google Earth Street View, remember that you can swipe or use your mouse to rotate the view because whatever you are looking for might be off to one side of the view that comes up. After you find each landmark, record it next to the number of the challenge on your paper. Tip: Click the plus sign on Google Earth to zoom in before you enter the street view.

Here are the six landmarks that you are seeking:

• For McCullough’s Leap, you are looking for the statue of a Mingo Indian.

• For the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Passenger Train Station, you will be looking through the entrance arch for West Virginia Northern Community College.

• For the Madonna of the Trail, you will be looking for the Madonna of the Trail Monument located near National Road.

• For the Wheeling Suspension Bridge, you will be looking for the eastern entrance to the bridge.

• For Shepherd Hall AKA Monument Place, you will be looking for the stone house.

• For the West Virginia State Fair Exhibition Hall on Wheeling Island, you will be looking for the Exhibition Hall Building, which was also known as the Wheeling Island Roller Rink.

Here are the GPS Coordinates for your challenges:

• Coordinates for challenge 1: 40° 3.334′ N 80° 40.158′ W

• Coordinates for challenge 2: 40° 3.808′ N 80° 43.788′ W

• Coordinates for challenge 3: 40° 3.834′ N 80° 43.286′ W

• Coordinates for challenge 4: 40° 2.557′ N 80° 39.490′ W

• Coordinates for challenge 5: 40° 4.229′ N 80° 43.437′ W

• Coordinates for challenge 6: 40° 4.752′ N 80° 43.367′ W

• Earl Nicodemus is retired after 40 years as a professor of Instructional Technology at West Liberty University. He helped to form the West Liberty Historical Society, and he and his family maintained the historic West Liberty Cemetery from 1985 to 2016. In 2016, Earl was named as a West Virginia History Hero. His other interests include gardening and fishing.