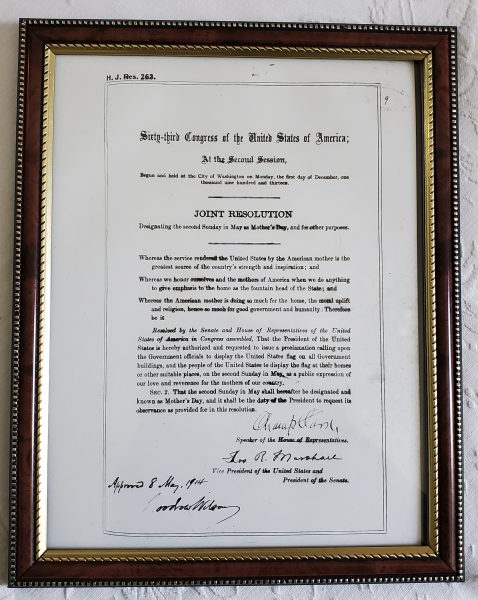

On May 8, 1914, the United States Congress officially designated the second Sunday in May as Mother’s Day and the tradition is still holding strong. As of 2021, Mother’s Day will be celebrated by an estimated 83% percent of American adults and has become the nation’s second-highest gift-giving day after Christmas. It’s a day set aside for Americans to express their appreciation for their mothers—and retailers, florists, and greeting card companies may find themselves thanking its founder Anna Jarvis for their profit margins. Despite its association with gift-giving, Jarvis spent the majority of her adult life fighting against the holiday’s increasing commercialization. Over time, Mother’s Day departed so drastically from Jarvis’ vision that, a few years before her death in 1948, Jarvis created a petition to rescind the holiday.

Why did Jarvis abhor so much of what her holiday became? In Memorializing Motherhood: Anna Jarvis and the Struggle for Control of Mother’s Day, author Katharine Lane Antolini sets out to explain Jarvis’ complicated relationship with the holiday she founded. By tracing the holiday’s origins, influences, commercialization, and interpretation in an ever-changing society, Antolini explains Jarvis’ concept of the holiday and why she so vehemently wanted it to remain unaltered.

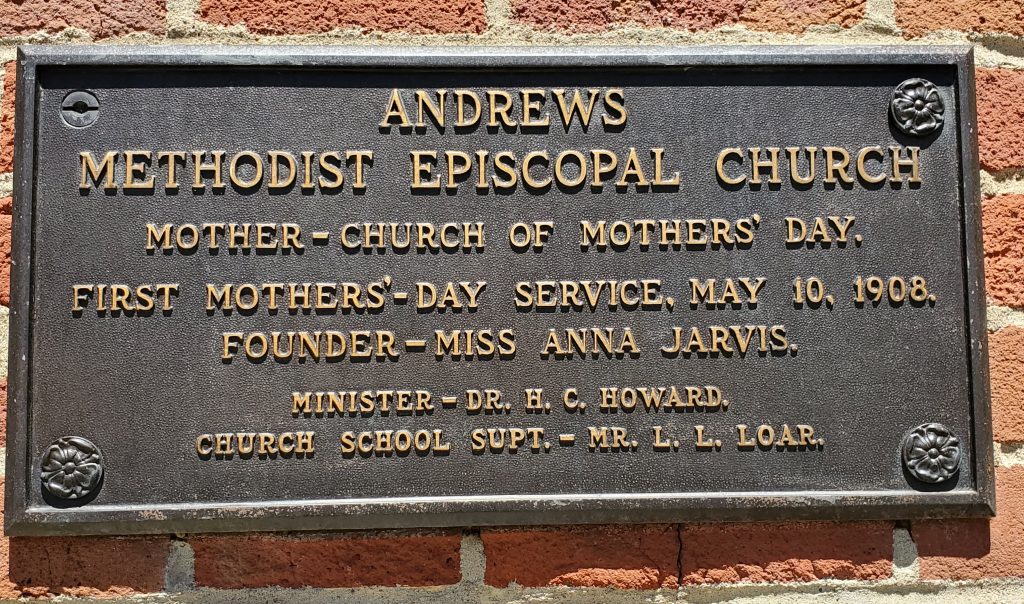

Though holidays celebrating mothers have existed since antiquity, the creation of a national Mother’s Day is credited to Jarvis for a number of reasons. First, it was Jarvis who arranged for the first official Mother’s Day to be celebrated in 1908 in Grafton, West Virginia, and it was her fervent letter-writing campaign and distribution of pamphlets, programs, and pins that ultimately made it a widely-recognized holiday. Moreover, Jarvis poured her own money, time, and creativity into the project and, unlike others who might be credited as founder, maintained a commitment to the cause. Though several contemporaries of Jarvis’, including Jarvis’ own mother Mrs. Ann Reeves Jarvis, laid the groundwork for a day set aside to celebrate mothers, Antolini ultimately concludes that Jarvis should be recognized as its founder due to her extensive work to have the holiday nationalized and recognized.

As the holiday grew in popularity, Jarvis felt compelled to wage an endless war against the country’s retailers who, she believed, unjustly profited from her intellectual property. Jarvis didn’t want anyone to profit off of Mother’s Day or any of its related emblems nor did she wish to see her vision altered. In an attempt to combat this, Jarvis had multiple patents and trademarks to ensure her Mother’s Day wouldn’t be tarnished by greed; however, many corporations were willing to risk a lawsuit and Jarvis’ ire for the opportunity to make a lucrative profit. She was livid that the floral and greeting card industries were making large amounts of money thanks to her ideas and deeply disliked the holiday’s growing commercialization.

In addition to the holiday being warped by commercialization, Antolini notes that Jarvis’ vision was challenged by the changing social ideas of motherhood. Jarvis’ concept of motherhood, cemented in Victorian sentimentalism, was very home-centric: women existed almost entirely within the home sphere and had a great deal of influence over it. In Jarvis’ era, mothers were the center of the home while fathers existed largely to be the breadwinner and an occasional playmate or disciplinarian for the children. Consequently, the father didn’t have nearly the influence of the mother. However, this dynamic began to shift as more women took on responsibilities outside of the home and fathers were called upon to have a more active role within it.

As fathers were urged to become more active participants in their children’s lives, proponents called for the creation of a Father’s Day and Parents’ Day. Jarvis vehemently fought against each: she considered Father’s Day a blatant attempt to capitalize on her Mother’s Day and cited that multiple American holidays already existed to honored fathers. What needled her more was the proposed Parents’ Day: could these “mother-haters,” demanded Jarvis, not give mother one day a year that was all for her? All of her letter-writing could not stop either, but Jarvis would perhaps be pleased to learn that neither holiday had the same staying power as Mother’s Day.

Though the majority of Americans continue to celebrate Mother’s Day, few adhere to Jarvis’ vision. Even in Jarvis’ own lifetime, she struggled to retain ownership of the holiday and ultimately lost the battle against commercialization and its interlopers. Despite this, one would argue that Jarvis’ work was not done in vain: Mother’s Day, though celebrated differently in the 21st century than it was in 1908, remains incredibly popular in the United States. Moreover, Jarvis’ tenacity and dedication paid off, as it is she and her hometown of Webster, West Virginia that retain the claim to fame. Jarvis’ childhood home in Webster still draws a considerable amount of tourists as does the International Mother’s Day Shrine in nearby Grafton where the first Mother’s Day ceremony was held. Interest in Jarvis herself hasn’t flagged, either: Antolini’s book is one of several recently published on the topic. Regardless of how Jarvis felt about her legacy at the end of her life, she may be heartened to know that American mothers still receive thanks and praise every second Sunday in May.

For those wanting to know more about Anna Jarvis and the history of Mother’s Day, I highly recommend Antolini’s book; I believe one would be hard-pressed to find a work about Anna Jarvis as well-researched, informative, and engaging as hers. The book is 219 pages in all but the narrative ends at page 158: the rest of the book is composed of an appendix, a detailed bibliography, and extensive notes. The book can be purchased through most major retailers or at the Wheeling Artisan Center Shop.

For those willing to drive a few hours, I also recommend visiting the Anna Jarvis Museum in Webster. The tour is very affordable (only $5 per adult) and its curator, Olive Ricketts, is extremely knowledgeable about Jarvis, Mrs. Reeves Jarvis, and the Jarvis family as a whole. If you aren’t able to visit around Mother’s Day, plan a trip for October – the museum is reportedly haunted by a few Jarvises!