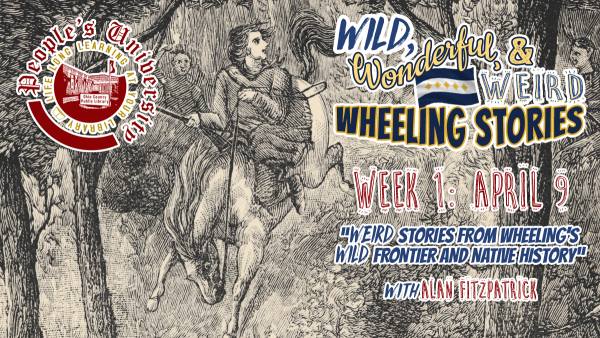

Editor’s note: On Tuesday, April 9, the Ohio County Public Library will launch its 26th People’s University, an eight-week series featuring weird, wild, wacky, whimsical stories from Wheeling, including: Native-American oddities, frontier follies, Civil War conundrums, Victorian unconventionalities, Progressive Era incongruities, political peculiarities, hotel hijinks, morbid mysteries and more! Let Weelunk give you just a little insight into these programs — but don’t miss the expanded presentations at the library!

There are many wild, weird and downright mysterious stories of Wheeling’s earliest colonial history, many connected and intertwined with the Native-Americans whom the first settlers came in contact with when they arrived in 1769.Here is a sampling.

• An engraved rough stone tablet was found in rural Ohio County that records the death of someone “kilt by Injuns in 1744.” The epitaph sounds like the often reported casualty of the border wars of the time. Except for one thing. No English-speaking people were here in 1744 — not for another 25 years. Was the stone an elaborate hoax or real?

• Major Sam McColloch, the hero of the first siege of Fort Henry who escaped capture by the Indians by leaping his horse over the precipice of Wheeling hill in 1777, had a premonition one morning in 1782, before riding out on a scout. What caused him to give pause?

• It has been said that the famed frontier scout, Lewis Wetzel, was the only known man on the frontier who could load his rifle with gunpowder and lead bullet while being pursued on the run by Indians. Did this somehow have an effect upon him that caused increasingly erratic behavior later in life?

• Wyandot Native warriors attacked Fort Henry in 1777 using deception to open the battle by luring militiamen out of the fort where they could be ambushed. But did the Wyandot have another motive in attacking Wheeling that involved kitchen utensils? Was the attack on Wheeling really part of a larger “Pots and Pans” war?

• In what is now Ohio, Native people in the late 1700s who had never been to Fort Henry and Wheeling talked about the notoriety of the place. What was it that perpetuated the image of Weel-lunk in their minds, and why did it cause Ebenezer Zane to not change the name of Weel-lunk to Zanesville, Zanestown or Zanesburg? Rightly, should Zane have really named it Kanora?

• Daniel Boone, later in life, revealed to his family and historians that he occasionally dreamt of his father with whom he did not have a close relationship in real life. Upon having such a dream, what was it that always followed the dream in real life that made him shudder?

• During the border wars on the frontier with the Native-Americans, the Wyandot War Chief, Dunquat the Half King, had a right-hand war captain in the field who personally set war parties against the frontier settlements with great success, including the ambush and death of Major Sam McColloch in August of 1782. His Wyandot name was Zhau-Shoo-Too and the English at Detroit called him “Coon.” But who was he really?

• The youngest brother of the Zane family, Isaac Zane, had been captured and adopted by the Wyandot Nation in the Ohio Country. He married a woman named Myeerah, whose name meant “Walk-in the-Water” but was called “The White Crane” because of the paleness of her skin, thanks to her French-Canadian mother. Her father was a sachem or chief of the Wyandots named Tarhe. Marrying the daughter of a noted warrior and chief would have precluded something of Isaac that he would have kept secret from white acquaintances and his own family after the end of the American Revolution in the west. What was his deep, dark secret?

Don’t miss Tuesday’s talk when Alan divulges much more about Wheeling’s wild frontier and Native history!

All programs are free and open to the public. Patrons may attend as many classes as they wish. There are no tests or other requirements. For more information about the People’s University email the library, call 304-232-0244 or visit the Reference Desk.

• Alan Fitzpatrick was born and raised in Saskatchewan, Canada, before coming to the United States. He graduated from Kent State University with a degree in psychology and took a job at the West Virginia Penitentiary as a classification counselor, and he later owned and operated a retail business with his brother for 33 years. Alan has written four non-fiction American history books detailing the Native-American side of the story of wilderness war during the 1700s. Retired, Alan continues to lecture on history in the tri-state area and devotes his time to oil painting portraiture.