When West Liberty was settled, the region had a lot of oak trees. In addition to supplying lumber for the building needs as the community grew, those oaks also provided a plentiful supply of oak bark to the two tanneries which were located in West Liberty. The larger tannery was called “Montgomery’s Tan Yard.” It covered an entire acre. One source indicated that it was located on three lots later owned by Bonar, Dixon, and Shields families. I am unsure where those lots were located, but I think that the location was likely somewhere near the creek since a tannery required lots of water. The other tannery was called “Mills Tannery.” It was somewhere in the southwestern part of town. I know even less about the exact location of the Mills Tannery, but it also occupied a good sized lot and would have also likely been near to a water source.

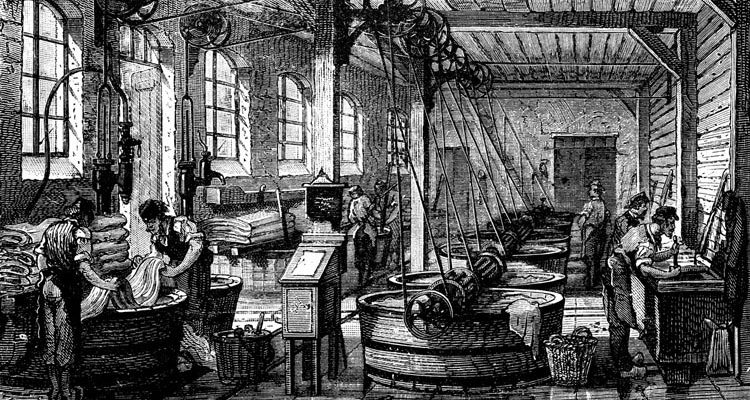

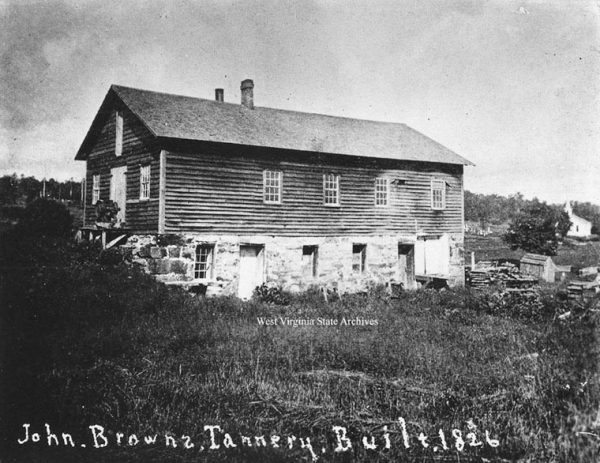

The tannery would likely have consisted of a couple of buildings including a covered shed for storing and grinding the tan bark and a large heated building for fleshing, tanning, and working the hides. The tannery also needed dry storage for the wood ashes or lime used in the hair removal process and for the raw hides and the finished leather. If the tannery operated in the winter, it needed a large indoor heated area to hold the vats or pits used in the tanning process. Very early tanneries often only operated during summer months. By the mid-1800s, a typical tannery operated year round inside a large heated building.

The first step in the tanning process was rehydrating and fleshing. Skins usually arrived at the tannery salted and dried. The tannery would rehydrate them by soaking them in water to wash out the salt. After rehydrating the hides, the workers stretched them over logs or boards and scraped the remaining flesh and fat off of them. Then, the tanners removed the hair from the hide.

.

.

Leathermaking: The Popular Cyclopeadia of Useful Knowledge, 1888

To loosen the hair, the hides were soaked in an alkaline solution. Early tanneries used a homemade lye solution which was prepared by mixing wood ashes with water. Some early tanneries also collected urine which they added to the homemade lye solution to hasten the removal of the hair from the hides. The soaking could take a couple of weeks during which time the lye water might be changed a couple of times. Where it was available, lime was used in place of lye. Although I have not found documentation of any limestone kilns in West Liberty, we know that there were at least two brick ovens operating in the town in the mid 1800’s. The old West Liberty Academy building and the old federated church building were both constructed using locally made bricks. In the mid-1800s, most mortar was made using lime. Since limestone was readily available in the West Liberty area and there was plenty of fuel in the form of wood and coal, it is logical to assume that at least one limestone kiln was located somewhere nearby. Sometimes, the folks who operated brick ovens also had limestone kilns since the process was similar and since people needed mortar for the bricks. Therefore, lime was likely available to the West Liberty tanneries by the mid-1800s. Some putrefaction took place while the hides were soaking in the lye vats, so the tannery emitted a significant stench. For this reason, most tanneries were located some distance away from the homes in the community.

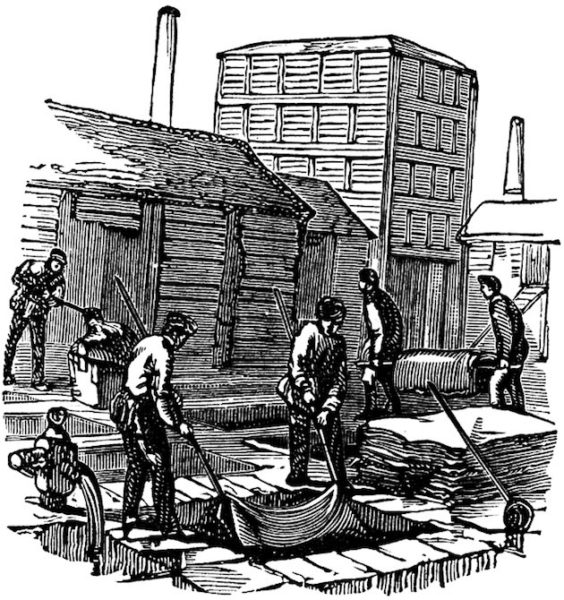

After soaking the hides in the lye or lime water, the workers rinsed them and then stretched them over a plank or large log and used a fleshing knife to remove the hair. Removing the hair was hard work. After scraping off all of the hair, the hides were placed into running water to wash out any remaining lye. This washing could last for several days and involved turning the hides several times to be sure that all of the lye was removed.

Removing the Flesh from the Hides – circa 1920

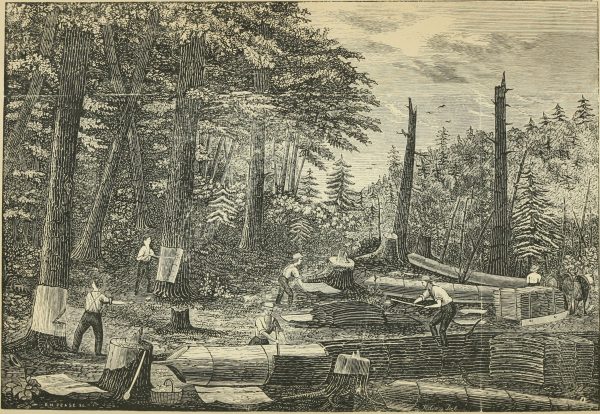

After the hides were washed, they were put into stone or wooden vats which were then filled with water saturated with tannin obtained from the oak bark. (The Latin word “tannum” actually means “oak bark.” To obtain the tanning bark, oak trees were harvested in the spring after they had come out in leaf and when they were actively growing. The old tanning bark collectors followed the moon signs to determine when to harvest the bark. The best time was as close as possible to the new moon at the end of May. The bark was removed from the trunk of the standing trees by using an axe to hack a V-shaped cut through the bark all the way around the base of the tree. Another similar cut was made about three feet higher on the tree. The bark was split vertically between the two cuts. Then, the workers used spud bars to peel the bark from the trees. Often, a second section of bark was removed from the tree trunk before the tree was felled. After the tree was felled, the bark was removed from the rest of the tree. The bark was flattened and dried, and then sold to the tannery.

Harvesting Tanning Bark (The trees in this picture are hemlocks.)

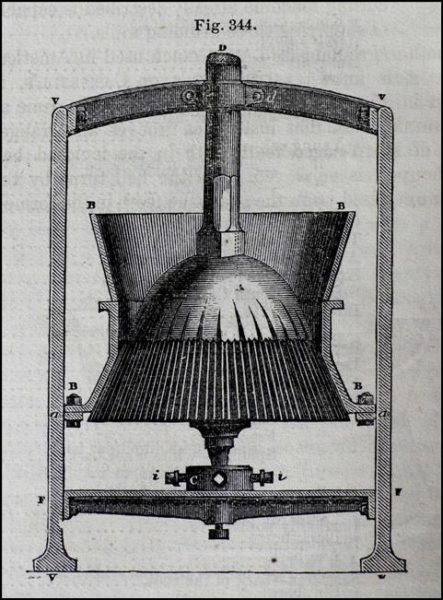

The tannery stacked the dry tanning bark in a storage shed until it was needed. The best tanning bark came from oak or hemlock trees. In the region around West Liberty, most of the tanning bark came from oaks. In order to extract the tannin, the oak bark had to be crushed or pulverized. A bark mill was used to pulverize the dried bark. In the 1700’s, a tanning bark mill amounted to a large stone wheel which rolled over the bark. The wheel was attached to an overhead pole which was pulled around in a circle by a horse to crush the bark. By the mid 1800’s most tanneries had cast iron burr mills which were also powered by horses. The finer the bark was ground, the better.

1800’s Cast Iron Tanning Bark Mill

The crushed or ground bark was soaked in water to extract the tannin. Typically, a layer of pulverized bark would be put into the bottom of a stone or wooden vat and covered with water. Then, a layer of hides was added. More bark was spread onto the hides, more water was added, and then another layer of skins was added. The process was repeated until the vat was filled with the top layer consisting of about two inches of tanning bark. After the hides soaked in the tannin for several weeks, they were washed in running water for a week or more. Then, workers used wooden tools to squeeze out as much water as possible and the hides were allowed to dry. As the hides dried, the workers worked them to make them supple sometimes adding oils, coloring treatments, and other finishing agents to them to complete the process.

A typical 1800’s tannery – This one was operated by John Brown (Note the storage buildings)

My research on the tanneries in West Liberty is still a work in progress. I don’t know for sure exactly where they were located or the dates when they operated. Since a tannery required a plentiful supply of fresh water, they were likely located somewhere near the creek. If anyone can provide more information about them, please post a response and share it with us! If you find an error in this story, please let us know about it!

I would also like to find out if there was a limestone kiln somewhere nearby. If so, it would have likely been a somewhat tall brick or stone structure. The upper part held the limestone rocks and a fire built in the bottom provided the heat. If anyone knows of the remains of such a structure, please share that information. To find out more about what it would have looked like , just do an Internet image search on colonial limestone kilns.