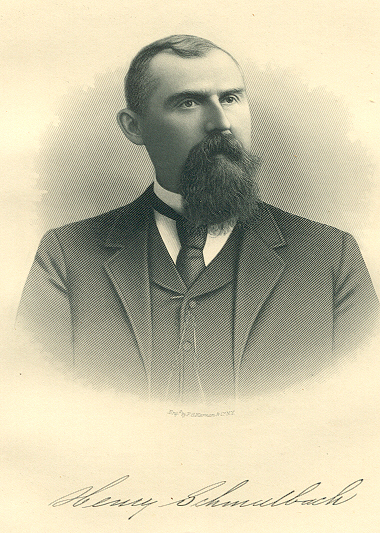

Henry Schmulbach: entrepreneur, beer baron, philanthropist and socialite. These are all words that describe one of Wheeling’s most influential and successful businessmen.

Schmulbach built an empire during an era when Wheeling was ripe for success. Many of his endeavors still can be found in Wheeling today. The legend of Schmulbach and his free-spirited lifestyle will forever be a part of Wheeling’s history. One hundred and forty years ago today, on Aug. 14th, a young Schmulbach was involved in an altercation at a tavern and was charged with a murder that threatened to break up all of the lucrative business interest he had achieved in such a short time. The goal of this post is to provide readers with a brief biography of Schmulbach, his accomplishments and to describe what happened on a tragic August night in 1878.

Henry Schmulbach was born in Germany on Nov. 12, 1844, during a time of turmoil in German history. During the late 1840s and early 1850s, Germany was experiencing a failed revolution that led to an uncertainty in social and political conditions. These unpredictable conditions forced many Germans to escape the inequalities of their homeland for the United States of America. The Schmulbach family decided to follow the passage of hope as thousands of other German families already had.

John Schmulbach and his wife Anna arrived in Baltimore, Md., on Sept. 4, 1852, with their two children Mary and Henry, and Henry Schmulbach’s aunt and grandfather. The family’s destination would ultimately be the bustling river metropolis of Wheeling, Va. Situated along the banks of the Ohio River, Wheeling was resting upon the banks of industry, commerce and technology. Wheeling, a city that worked hard for its prosperity, was earning the name “Gateway to the West” because America’s first highway, the National Road went through Wheeling. Also, the Wheeling Suspension Bridge served as a monument to ambition and assurance to immigrants; a symbol that anything could be accomplished in this land of opportunity.

When the Schmulbachs arrived in Wheeling, the town’s population was approximately 14,000 residents with a strong German community residing in the southern district. The town was thriving in the crafts of iron, glass and pottery because of the region’s abundant natural resources. To make Wheeling even more competitive, it received another transportation gift — a link to the B&O Railroad on Jan. 11, 1853. At age 10, Henry Schmulbach began taking advantage of Wheeling’s river traffic by securing positions on packet boats and learning at an early age the art of entrepreneurship. Packet boats were used to transport mail, passengers and various goods, and were quite frequent along the Ohio River. No evidence suggested Schmulbach received formal schooling. Instead, Schmulbach was educated on the river as a cabin boy on these boats.

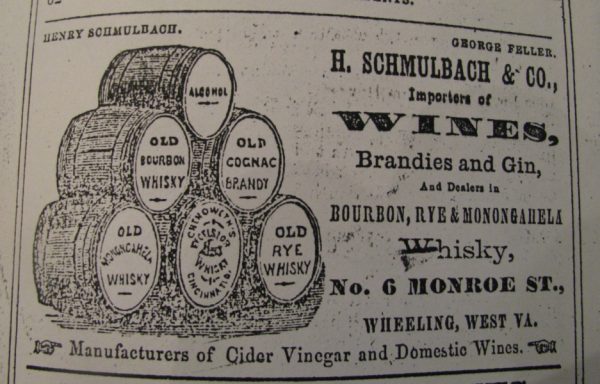

While not on the river, the church of the Schmulbach family was the First German Evangelical Lutheran Zion Church of Wheeling. Schmulbach was confirmed with the class of 1859, and he may have also attended classes that were held by the church to promote German heritage and language. As a youth, Schmulbach was also mentored by his uncle George Feller who owned riverboats and provided Henry with the foundation to start many of his own enterprises. The outbreak of the Civil War forced Schmulbach and Feller to stop working on the river because of the dangers of traveling. Although Schmulbach would never forget his river roots, in 1864 he started working as a clerk with Feller in the wholesale grocery business.

As Schmulbach’s business sense was being defined at this time, so were his pleasures. Schmulbach gained the reputation of being a gambler.

By 1867 Feller and Schmulbach shifted their interest toward the wholesale liquor business. As partners, they set up shop on Monroe street.

In 1870, Feller retired, and for the next six to seven years Schmulbach prospered in the wholesale liquor business while also gaining interest in various stocks, riverboats and hotels that catered to river traffic. Of the hotels, the most notable was the James Hotel on Water Street and the Sprigg House on Main Street. In 1873 at age 29, Schmulbach moved into a Victorian style residence on 2311 Chapline St. where he would live for the better part of his life.

Remaining on the south side of Wheeling in the German section, this purchase signified the progressions Schmulbach made as a businessman. From a poor German immigrant boy who worked on the river to a man owning his own business, he served as an example of why Wheeling was becoming a “melting pot” of European immigrants.

In the 34th year of Schmulbach’s life, he would encounter a series of events that would add to his reputation. On Aug.14, 1878, between the hours of 9 and 10 p.m., Schmulbach and “Ham” Forsythe arrived at Frank Walters (president of Nail City Brewing) Two Mile House.

According to Walters, Schmulbach was driving a two-horse buggy when he pulled up to the tavern with his companion. Entering the tavern with Forsythe, Schmulbach asked for some wine and inquired to Walters if a man sitting nearby was Mr. Rush. Upon replying yes, Schmulbach and Mr. Rush shared a drink and conversation. Meanwhile, heavily under the influence of alcohol, Forsythe began swearing in a disorderly fashion and started to boast that he could whip any Dutch turner in the room. He was soon advised that he should stop talking in that manner. Forsythe later made efforts to interrupt the conversation between Schmulbach and Rush. Irritated, Schmulbach told Forsythe to go outside and sit down. Forsythe went outside, but he did not sit down. Instead, he took off with Schmulbach’s buggy and horses. Schmulbach, an avid fan of horses, thought of these animals as his pets, and at that moment, they were being raced east on the National Road by Forsythe.

After Schmulbach and Mr. Rush finished their drinks, Schmulbach invited him for a ride in his buggy. Agreeing, both men went outside, only to discover that Schmulbach’s buggy and horses were missing. Schmulbach remarked, “That is mean. I would like to know who did it.” Schmulbach would make inquiries to people on the pike, and borrow a team to retrieve his own, which was said to be near Stamm’s Tavern (across from Wheeling Park).

The first sight of Forsythe at Stamm’s Tavern was by William Fendt who noticed a buggy driving at a rapid pace toward the inn. Fearing that his own horse may scare, Fendt made an attempt to slow down Forsythe who replied, “I can drive this team.” Forsythe took off a short distance only to return again and shout, “I will show you how I can drive,” and took off yet again. Meanwhile, William Stamm and a group of ladies were sitting near the entrance of the Stamm House when Forsythe drove past them in one of his rapid dashes. Startling the women, they thought it safer to move inside the tavern. Forsythe then pulled up to the hitching post and stated, “This is Henry Schmulbach’s team, and my name is Ham Forsythe.” During another mad gallop, onlookers Ed Mendel and William Fendt successfully captured the team from Forsythe at a location referred to as Pryor’s Hill near Stamm’s stables.

Mendel provided the following testimony that appeared in the Wheeling News Register on Aug.16, 1878.

I got into the buggy with Forsythe and he asked who I was. I replied “No Difference.” I sat on the right side of the buggy. Forsythe asked if I were going to drive the horses, I said watch and see me. We talked of several things. He was going to trot a match with Spaulding Wallace for $500, and Schmulbach had put up a check. I told him that I had saved $500 for Mr. Schmulbach.

By this time, Schmulbach had appeared and demanded his team. Mendel replied that he had the team and that Schmulbach could take them away. Schmulbach approached his buggy and said, “I will teach you to take or steal my team.” He then attached his foot to the right hub of the buggy and attempted to strike Forsythe over the knee of Mendel, after which Mendel held off Schmulbach. This action provoked Forsythe to say, “I will meet him,” and he jumped off the buggy. Schmulbach ran to the other side and collided with Forsythe. At this point, the two men were entangled. Initially, Schmulbach was underneath Forsythe, but testimony states that Schmulbach quickly rolled over on Forsythe and began to strike him several times. Mendal intervened by pulling Schmulbach off Forsythe, which prompted Schmulbach to ask if he was against him, too.

Reports state that, after the incident, Schmulbach left with his buggy and returned to Walters Two Mile House where he approached the gate and asked Walters for some water to cool his horses. With froth covering the horses, Walters said they were too overheated and thought it best to let the horses rest before watering them. Schmulbach commented to Walters that he had given Forsythe a good licking and that, in the process, his shirt collar was torn. As the two men were talking, a wagon drove up to the tavern. By candlelight, Walters went outside with Schmulbach to see that Forsythe was lying in the back of a light spring wagon driven by Mr. Stamm. Although bruised, bleeding and unconscious, Forsythe was still alive. Walters suggested to Schmulbach that he, “ought not to take such a man riding with him.” Schmulbach replied, “Forsythe is a poor man and wanted a ride.” Schmulbach appeared sorry for his brutality against Forsythe and said, “I did not think I hurt him; let him stay here for the night.”

Instead, Mr. Stamm drove to the unconscious body of Forsythe to the courthouse in Wheeling. Soon after his arrival, a crowd gathered around with curiosity as Mr. Stamm told the spectators of the happenings at his tavern. Bystanders were shocked by the current state of Forsythe. Shortly after his arrival to the courthouse, Forsythe died. Those who had seen Forsythe earlier in evening reported that he appeared to be “in the enjoyment of excellent health.”

Soon afterward, a coroner’s jury was summoned, and after about of day of gathering evidence and testimony, the jury came to the following verdict: “That Hamilton Forsythe came to his death from concussion of the brain, resulting from blows from the fist of Henry Schmulbach, on the National Road, near the Four Mile House. …” Schmulbach then gave himself up to the law and was arrested, after which he posted $10,000 bail.

One question that occurs while examining this incident is: Why was Forsythe with Henry Schmulbach? Horse racing may be the obvious answer and ironically, Forsythe would have inherited $2,500 from his father’s estate in a few days.

The trial was originally scheduled for November, but after delay, the trial finally took place in February of 1879. After normal trial procedures, and much of the same testimony that was given in August, the jury deliberated a half hour, and upon re-entering the courtroom, the sheriff had to give several notices to the packed courtroom to maintain order. The jury’s final verdict was that Henry Schmulbach was innocent of murder. Most likely the jury took into consideration Forsythe’s actions, Schmulbach’s act of self-defense and the fact that Forsythe may have hit his head on rough stones upon colliding with Schmulbach that caused to concussion of the brain. One would also have to consider Schmulbach’s financial standing in the community and his wide network of friends and associates. Schmulbach would probably gain social opponents, but he did not seem to mind. He was quite comfortable living at 2311 Chapline St. with his sister Mary and a brother and sister who had been born in the states, Conrad and Elizabeth.

The trial was originally scheduled for November, but after delay, the trial finally took place in February of 1879. After normal trial procedures, and much of the same testimony that was given in August, the jury deliberated a half hour, and upon re-entering the courtroom, the sheriff had to give several notices to the packed courtroom to maintain order. The jury’s final verdict was that Henry Schmulbach was innocent of murder. Most likely the jury took into consideration Forsythe’s actions, Schmulbach’s act of self-defense and the fact that Forsythe may have hit his head on rough stones upon colliding with Schmulbach that caused to concussion of the brain. One would also have to consider Schmulbach’s financial standing in the community and his wide network of friends and associates. Schmulbach would probably gain social opponents, but he did not seem to mind. He was quite comfortable living at 2311 Chapline St. with his sister Mary and a brother and sister who had been born in the states, Conrad and Elizabeth.

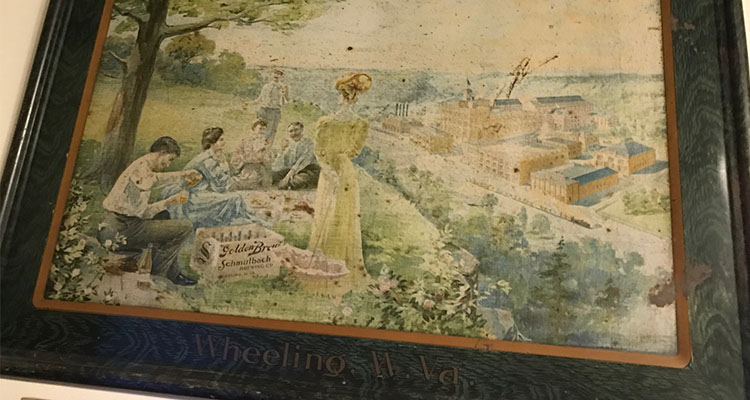

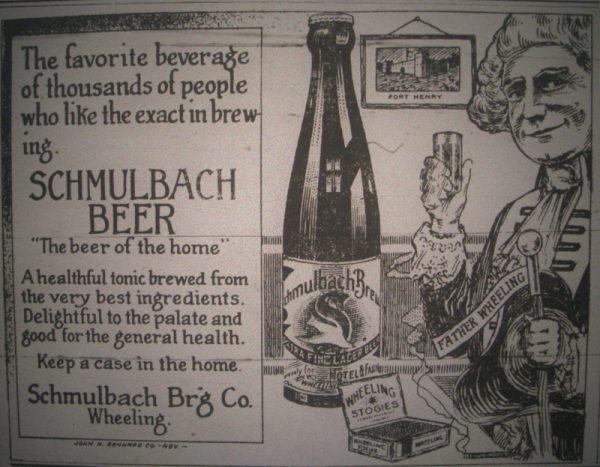

With a keen business sense, Schmulbach had been acquiring shares of various stocks, and in 1881, he was the leading stockholder of the Nail City Brewing Company and was named president in the same year. Serving as president for one year, he proposed that the brewery’s name be changed to the Schmulbach Brewing Company. Stockholders agreed, and from that point on, Schmulbach would expand the brewery that would become one of the largest and well-known in the tri-state area.

Aside from the brewing industry, Schmulbach also was involved in various other interest. In 1890, the book, Prominent Men of West Virginia, described Schmulbach as a man “possessing many elements of solid popularity” and “one of Wheeling’s most enterprising, public-spirited citizens.” Throughout his business career, he was involved in the following enterprises:

- Wheeling Iron and Nail Company

- Junction Iron and Nail Company

- Aetna Iron and Nail Company

- Director of the Top Mill Company — later Wheeling Steel

- Wheeling — Cincinnati Steam Boat Company

- Fairmont and Clarksburg Railroad

- President of the Lime and Cement Company

- President of the Ohio Valley Fire Insurance Company

- A stockholder and director of the Hobbs Glassworks

- Director and treasurer of the Washington Hall Association — later known as the Grand Opera House

- Built Mozart Park and the famous railway incline

- Director and then president of the German Bank

- President of the Schmulbach Brewing Company

- President of the Wheeling Bridge Company

- President of the Board of Public Works

- President of the National Telephone Company

- Owned the Schmulbach stock farm on Wheeling Island

- Owned a stock farm in Kentucky

- Member of the school board

Schmulbach could also be described as a philanthropist. In the year 1900, he created and donated the Riverside Park monument in dedication to all who have served their county in the time of war.

A significantly larger gift to the city of Wheeling would be the Schmulbach Building. Opening in 1907, it was the tallest and most advanced building in the state of West Virginia.

During this era, Schmulbach also became one of the most prominent racehorse owners in the U.S. He commonly visited the popular racetracks of the era and was a frequent visitor of Kentucky.

One example of his love for the trotters would be his purchase of the racehorse Baldy McGregor for $15,000. Schmulbach raced the horse once and sold him in a consignment sale for $16,000 in 1913, the same year he sold off all of his horses. The total amount received for the consignment sale was $32,000.

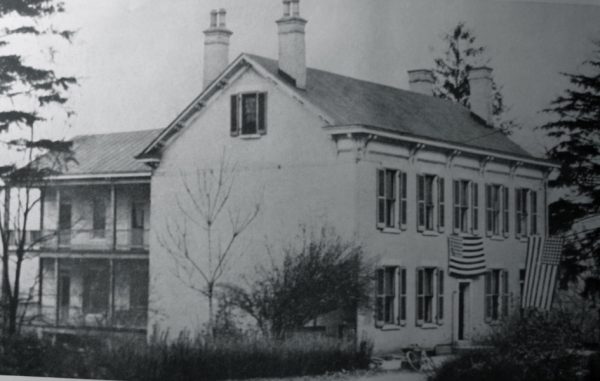

By 1913, though, Schmulbach began disposing of most of his business ventures to live a quiet life in retirement at his newly constructed mansion near Roney’s Point.

Still serving as president of the Schmulbach Brewing Company and the German Bank, he had settled down to quieter hobbies, his favorite being his greenhouse at Roney’s Point, the largest in the area.

The mansion was intended to be built for his sisters, but Elizabeth died in 1902, and Mary died 1912 before the mansion was finished. The 20-plus-room mansion would have seemed pretty lonely, and as the story goes, that’s what probably prompted Schmulbach to marry Eva Pauline Bertchy. Schmulbach was 69 years old, Pauline was 48, and she is said to have served as the hostess of the majestic Roney’s Point mansion.

Schmulbach would live there for two years, but in the early summer of 1915, just one year after his brewery closed because of prohibition in West Virginia, he became very ill and died on the evening of Aug. 12, 1915.

His funeral occurred on a Sunday afternoon at the mansion. Automobiles filled the fields and special streetcars were taken from Wheeling to Roney’s Point, and from there wagons and cars would take mourners on a scenic 4-mile trip to the mansion. Schmulbach was buried the next day at Greenwood Cemetery, and his funeral procession was the first in Wheeling to completely consist of automobiles.

Within a year, Pauline sold the mansion to the county for $125,000, and shortly afterward, the estate was turned into a poor farm. Then, in the 1930s and ’40s, the estate was also used as a TB sanitarium, and a wing was added to the mansion.

By 1961 the mansion was no longer being used, and in 1967, the property was sold to the state for $1. The state abandoned the mansion saying it was beyond repair, and they constructed a new mental health facility just down the road.

On the early morning of Oct. 2, 1975, the mansion burned, and only the shell remained.

While only the ruins of his mansion remain, the spirit and legend of Henry Schmulbach are alive and well in the study of Wheeling history, and throughout the town itself.

(Photos provided by Ryan Stanton)

• Ryan Stanton is a 2002 graduate of Wheeling Park High School. In 2006 he graduated from West Liberty State College with a bachelor’s degree in history and later earned a master’s degree in social studies education from West Virginia University. For nine years, Ryan has been a social studies teacher at Wheeling Park High School where he teaches AP U.S. government and politics and the history of Wheeling.