Originally published July 19, 2021

Taking a first pass through Wheeling’s history, you would certainly notice the prevalence of industries such as glass, nails, stogies, and steel. Dozens of books have been written about the city’s factories and there is a reason why Wheeling’s nickname, the “Nail Capital of the World,” still persists. Locals and visitors alike love to discover old Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel trash cans and Marsh Wheeling stogie boxes at nearby antique stores.

However, most people don’t realize that Wheeling was also home to a powerhouse pharmaceutical company, one that became the owner of one of the most popular medications in the world…Bayer Aspirin.

Two High School Friends and a Buggy

At the beginning of the 20th century, William E. Weiss and Albert H. Diebold went into business together to sell their patent medicine, Neuralgine. Weiss and Diebold had been friends in high school in Canton, Ohio before Weiss attended and graduated from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Diebold worked as a druggist in Sistersville, West Virginia.1

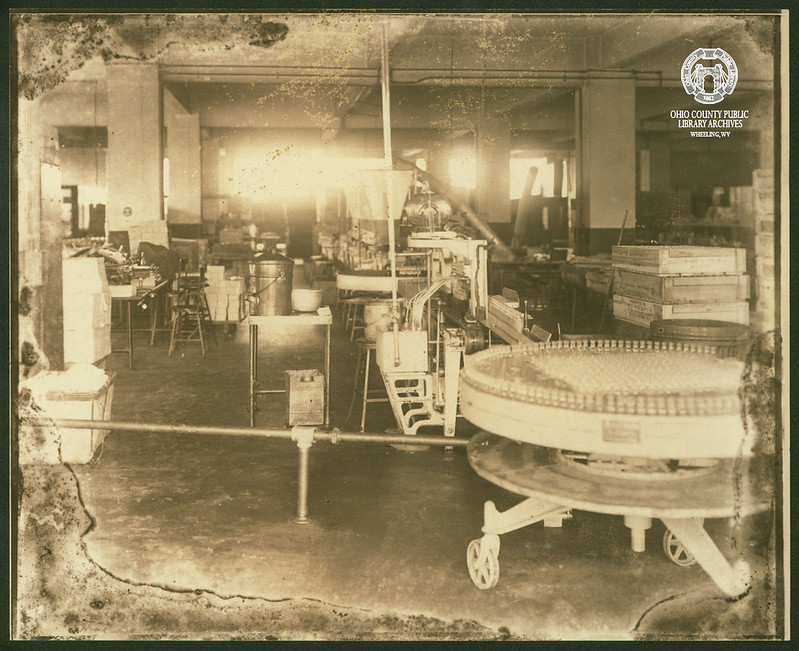

In 1901, Weiss and Diebold formed the Neuralgyline Company in Wheeling with three local partners and began to drive around the local area in a buggy, selling their sole product and nailing advertisements to roadside trees and fences.2 Curiously, to this day, other than being a general pain reliever, no one knows for certain what the ingredients of Neuralgine were—the best guess is that it was probably an acetanilid or a different coal-tar analgesic.3 At the start, their business operated out of only two rooms on the second floor of a Wheeling building at 1128 Market St. Their first year of sales produced $10,000, but by their second year, that number increased six-fold to approximately $60,000 (a little less than $1.9 million today).4

After their success became apparent, Weiss and Diebold realized their limitations with only one product, so they decided to expand the company by purchasing and acquiring more product lines. They bought other patent medicine firms, such as the Knowlton Danderine Company, Sterling Remedy, the California Fig Syrup Company and more. The acquisition of these companies allowed them to add a variety of medicines to their product lines, such as laxatives, a dandruff remedy and a nicotine “cure” that had an unfortunate constipation side effect.5

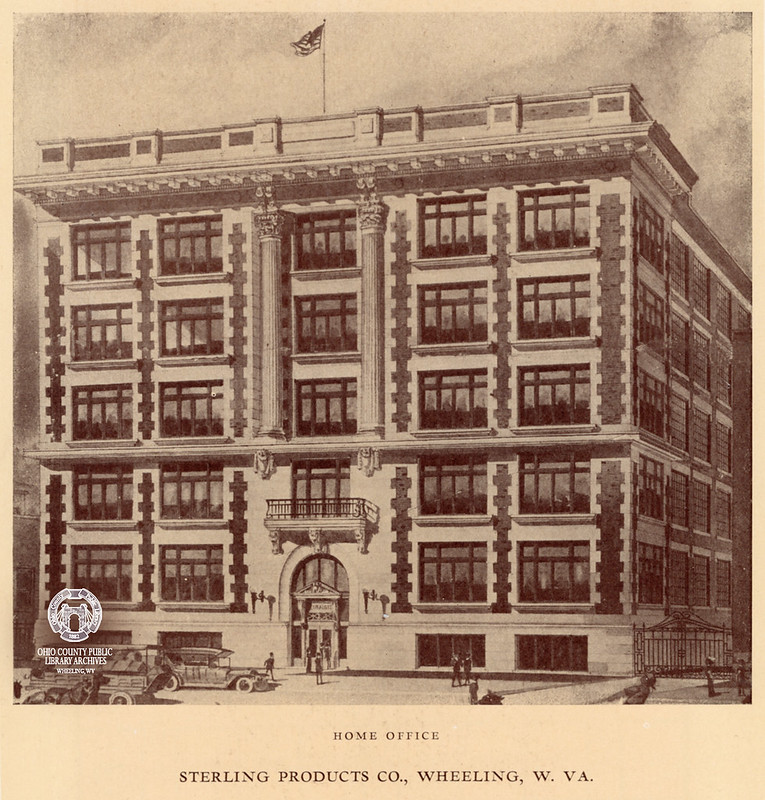

The expansion of the company prompted opening a brand-new building on 19th Street in Wheeling in 1914. The relatively ornate multi-level building was designed by the famous local architect, Charles W. Bates, who was also responsible for other Wheeling landmarks such as the Capitol Theatre and Edemar (now the Stifel Fine Arts Center).6

As their brand began to grow, Weiss and Diebold confronted the reality that their company’s name, Neuralgyline, didn’t exactly roll off the tongue. In 1917, they changed their name to the easier-to-remember “Sterling Products,” one of the trademarks they already owned from one of their many acquisitions.7 Later, after the consolidation of Sterling Products and United Drug in 1928, the company would be known as Sterling Drug, Inc.8 Even as Sterling Products moved their headquarters to New York City, it continued to operate its location in Wheeling and Weiss’s family remained based in the Friendly City.9

From Small Town Wheeling to Pharmaceutical Giant

Right as Sterling Products began to become a pharmaceutical powerhouse in the second decade of the 20th century, unrest and turmoil began to brew in Europe as World War I loomed and eventually erupted in mid-1914. A few months after the US officially declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, the newly-created Office of Alien Property Custodian began to seize the assets of German companies operating in the US.10

Acetylsalicylic acid—commonly known as aspirin—was first marketed starting in 1899 by The Bayer Company, a firm established in 1863.11 It became the world’s most popular drug, recognizable by the iconic “BAYER” cross stamped on the pills, packaging, and other ephemera.

However, unfortunately for them, Bayer was a German company.

Bayer’s assets in the US were seized on January 10, 1918 and sold at auction to Sterling Products in December of the same year for $5.3 million (almost $86.5 million in today’s currency). This included their factory and machinery in Rensselaer, New York, but most importantly, it covered the US patent for Bayer Aspirin.12

According to the book The Aspirin Wars, “Farbenfabriken Bayer had spent more than fifty years building the Bayer name into a global emblem of probity, quality, and technological prowess,” but due to the circumstances of the wartime business seizure, Sterling Products could swoop in and “would be able to sell many of the same products under the same name, using the same symbols, in the most important markets outside continental Europe.”13

Stuck Between a Rock and a Hard Place

While a world war made it possible for Sterling to acquire Bayer and its assets in the US, another world war threatened its empire. Even though Sterling had bought Bayer at auction after its assets were seized by the US government, during the interwar period, Sterling and I.G. Farben (Bayer’s new parent conglomerate company) entered into certain contracts and agreements.14 Sterling didn’t have personnel with the skill and expertise to run the specific machines or understand the patents for the new drugs it had acquired.15

These agreements would later come back to haunt Sterling—Weiss in particular. As World War II approached and the US and Germany ended up on the opposite sides of the conflict yet again, Sterling was stuck in the uncomfortable position between cooperating with an enemy’s company and needing that company to survive as a business. Ultimately, in 1939, Weiss decided to align Sterling even closer to I.G. Farben—offering to manufacture I.G.’s products to send to Latin America.16

In December 1941, after Sterling was found in breach of US anti-trust laws for its contracts with I.G. Farben, both Weiss and Diebold were forced to resign. Less than a year later, Weiss died in a car accident while on vacation in Michigan.17 I.G. Farben ended up directly supporting and cooperating with Nazi Germany. They intentionally infected and tested their experimental drugs on concentration camp prisoners, particularly at Auschwitz and Birkenau. The company and its employees’ crimes resulted in the IG Farben Trial, which was part of the larger Nuremberg trials against Nazi war criminals.18

Sterling Drug, Inc. would continue for another four decades before being acquired by Eastman Kodak in 1988, but Wheeling’s time as the birthplace of one of the largest pharmaceutical conglomerates came to an end.19 Almost a century after being built, the 19th Street Sterling building was demolished between 2011 and 2012—architectural remnants can still be seen in the Capitol Theatre.20 Today, Bayer Aspirin continues to be one of the most recognizable over-the-counter medications—thanks to a company that got its start with two men and a buggy in Wheeling.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “Wheeling Hall of Fame: William E. Weiss,” Ohio County Public Library, 1980, accessed June 7, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/-wheeling-hall-of-fame-william-e.-weiss-/414; “Albert Diebold, Drug Leader, Dies; Was Co-Founder of Company That Became Sterling Drug,” The New York Times, February 18, 1964, p. 35, accessed July 1, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/02/18/archives/albert-diebold-drug-leader-dies-was-cofounder-of-company-that.html

2 Joseph C. Collins and John R. Gwitt, “The Life Cycle of Sterling Drug, Inc.,” Bulletin for the History of Chemistry 25, no. 1 (2000): 22.

3 Charles C. Mann and Mark L. Plummer, The Aspirin Wars: Money, Medicine, and 100 Years of Rampant Competition, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), 50.

4 Collins and Gwitt, 22.

5 Mann and Plummer, 51.

6 “Charles W. Bates,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed July 6, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/5890.

7 Collins and Gwitt, 23.

8 Ibid., 24-25.

9 Mann and Plummer, 97.

10 Collins and Gwitt, 23.

11 Ibid., 23.

12 Ibid., 23.

13 Mann and Plummer, 52.

14 Collins and Gwitt, 25.

15 Mann and Plummer, 52-53.

16 Ibid., 99-100.

17 “W.E. Weiss Dies Of Crash Injuries,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, September 3, 1942, p. 1.; “Sterling Products Co. | Sterling Drug,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed June 7, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/sterling-products-co.-sterling-drug/7140.

18 “Holocaust Encyclopedia: Bayer,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, June 13, 2019, accessed July 8, 2021, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/bayer.

19 Collins and Gwitt, 22.

20 “Sterling Products Co. | Sterling Drug,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed June 7, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/sterling-products-co.-sterling-drug/7140.; Bekah Karelis, July 8, 2021, text message.