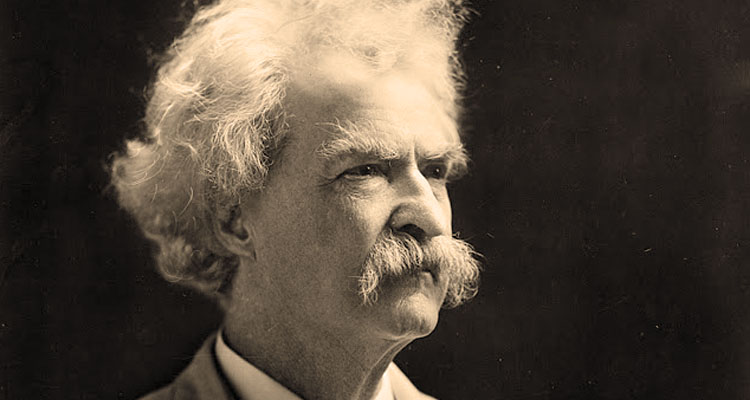

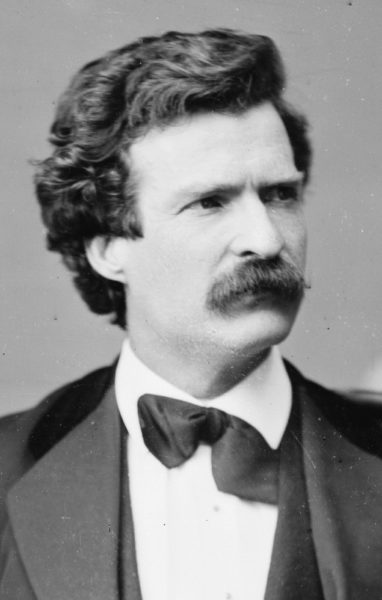

On Jan. 10, 1872, one of America’s most celebrated storytellers took the stage at Wheeling’s Washington Hall. An Intelligencer reporter described him as “a youngish-looking man of somewhere about thirty-five, not handsome, but having a bright and intelligent look … He was dressed very neatly in a black suit … He is clean shaven except with a heavy dark moustache; and his manner of wearing his hair, which is very abundant, shows that he is his own tonsorial artist.” Although his birth name was Samuel Clemens, most readers know this famous writer best as Mark Twain, and his humorous lecture in Wheeling that cold January night nearly 150 years ago is not his only connection to the Friendly City.

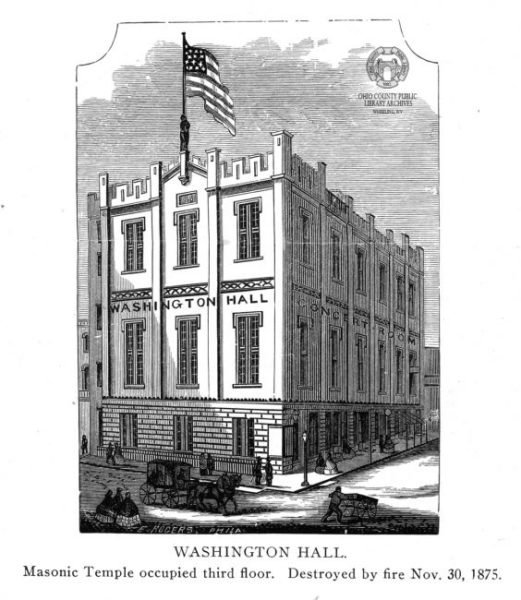

By the time Twain took the stage that night, West Virginia had celebrated its eighth statehood anniversary, Twain his second published travel book and Washington Hall its 20th year as a place for public assemblies. In fact, Washington Hall is best known as the site of the first Wheeling Convention of the people of North Western Virginia in May 1861, which eventually led to West Virginia’s secession from Virginia during the Civil War. Although the first Washington Hall burned in 1875, it was rebuilt in 1877 and opened its doors to the public with a production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1878. Records in the Ohio County Public Library’s archives record that the German Bank of Wheeling bought and extensively remodeled the structure in 1898. Washington Hall still stands in Wheeling today at the northeast corner of 12th and Market streets and is known as the Laconia Building.

“Roughing It”

Twain came to town to read from his newly published semi-autobiographical book, Roughing It, which took a humorous look at his adventures in what was then the Wild West of Nevada. He toured several states that year to read from the work, which The Intelligencer reporter noted was enjoyed by the audience of “the most intelligent and refined people of the city [of Wheeling] … if we may judge from the almost continuous laughter and applause that greeted it.” Twain enchanted his audience with tales of gold mining, horse wrangling and real estate speculation during his six-year trip starting in the early 1860s with his brother Orion Clemens, who had been appointed Secretary of the Nevada Territory.

Twain was no stranger to Wheeling. Known far and wide as a cigar smoker, Twain enjoyed the Marsh Wheeling toby most of all. Founded in Wheeling in 1840 by Mifflin Marsh, in its early years, the company sold hand-rolled stogies out of market baskets to crews and captains on Ohio River steamboats as well as Conestoga wagon drivers making their way to the frontier. Eventually, the Marsh Wheeling Stogie was known around the country and enjoyed by many well-known Americans, including Abraham Lincoln, P. T. Barnum, Annie Oakley and, later, John Wayne. In his autobiography, Twain writes about his penchant for the well-known smoke, “Then once more, changed off so that I might acquire the subtler flavor of the [Marsh] Wheeling Toby … I discovered the worst cigars, so called, are the best for me, after all.”

Twain was alluding to the way in which the Wheeling Stogie was made. It was hand-rolled of good-quality, but inexpensive Kentucky tobacco and meant to be affordable for Conestoga drivers, who picked them up for as little as four for a penny. In fact, the Wheeling Stogie was such a big seller that other manufacturers tried to copy it. According to Archiving Wheeling, the United States Circuit Court decreed in 1895 that only stogies made in Wheeling, West Virginia, could be called “Wheeling Stogies.”

Dueling Cousins

The Wheeling Register reported that before leaving for his next lecture (in Pittsburgh), Twain spent a few hours with a large crowd of Wheeling citizens who were “anxious to make the acquaintance of the man whose pilgrimage had so delighted them.” During this social event, he also made reference to his cousin Sherrard Clemens and “other distant relatives in the city,” which further delighted the group.

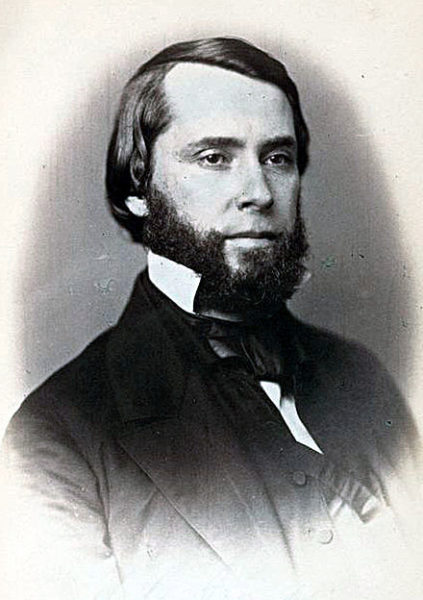

Sherrard Clemens was born, raised and later practiced law in Wheeling. He was elected to represent the Wheeling District of Virginia in the United States House of Representatives to fill a vacancy in 1852. He was later re-elected to the House in 1856, serving from 1857 to 1861. He disagreed with secession and made his position known at the Wheeling Convention at Washington Hall in May 1861. His stature and land ownership resulted in the town of Sherrard in Marshall County to be named after him.

Sherrard Clemens was part of a national scandal in 1858 when he was seriously injured in a duel with O. Jennings “Obie” Wise, newspaper editor and son of Virginia governor Henry Wise. Clemens had written an editorial that offended Wise, who was known to be a notorious duelist. After a volley of written exchanges, Clemens invited Wise to a duel. William A. Link reports in Roots of Secession, the two met on Sept. 17 at a racetrack near Richmond. They both missed their first three shots, but neither refused to compromise. Wise fired his fourth bullet and seriously wounded Clemens. Wise walked away unharmed. Although most reports of the duel state that Clemens was shot in his right testicle, other reports argue that the bullet entered his thigh. Either way, his injuries were significant and it was not long after that he moved to St. Louis where other members of his family had already settled.

According to his obituary in the May 31, 1880, St. Louis (Missouri) Post-Dispatch, Clemens died after a year-long battle with “a dropsical complaint,” likely congestive heart failure. He was destitute, and his friends were caring for his “daily necessities.” The writer extolls Clemens’ public speaking skills and political accomplishments but notes that he suffered with a lame foot as a result of the duel with Wise. In addition, the writer notes that Clemens had “a distant relationship” with the rest of the St. Louis Clemens clan.

Perhaps as a sardonic nod to his cousin’s misfortune, Twain ended his 1872 lecture in Wheeling by decrying dueling as a sin. In his autobiography, Twain writes, “I did not know what had become of Sherrard Clemens; but once I introduced Senator [Joseph Roswell] Hawley [of Connecticut] to a Republican mass meeting in New England, and then I got a bitter letter from Sherrard from St. Louis. He said that the Republicans of the North — no, the “mudsills of the North” — had swept away the old aristocracy of the South with fire and sword, and it ill became me, an aristocrat by blood, to train with that kind of swine.”

Did the Doctor Doctor the Tablet?

And here is where things get weird(er). Sherrard Clemens’ father, James Walton Clemens, is believed by some experts to have forged the Grave Creek tablet/stone. Clemens, a prominent Wheeling physician and inventor, helped bankroll the 1838 excavation of the Mound in Moundsville, just 11 miles from Wheeling. At 69 feet in height and 295 feet in diameter at the time of excavation, the Grave Creek Mound remains one of the largest conical burial mounds in the United States. The Adena Indian burial mound, built during the Woodland Period (around 1,000 BCE to 1 AD), was first spotted by European settlers in 1770. Joseph Tomlinson, founder of the city of Moundsville, was hunting deer when he saw the mound, which was then heavily forested. Tomlinson and many of his descendants were firmly against excavating the burial site, but all that changed in the 1830s with Jesse and Abelard Tomlinson, who believed the Mound was filled with exotic treasures to be unearthed.

Dr. Clemens was hoping to cash in on some of those discoveries, which is why he helped fund the dig. He was on site for two weeks of the excavation and meticulously recorded all findings and other details of the amateur dig. Regrettably, lack of knowledge of archaeological methods led to most of the important information about the Mound to be lost once the ground was opened.

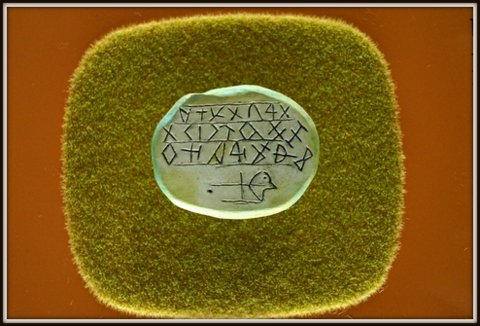

Although skeletons, beads, jewelry, pottery and other items were found inside the Mound, the major treasure Clemens was hoping to find did not reveal itself until laborers began working on the upper vault. An engraved sandstone tablet approximately 1 1/2 by 2 inches was reportedly found either on the floor of the upper vault or in a wheelbarrow load of dirt taken from the upper vault. At first, not much was made of this discovery, but the various published write-ups of the dig, including one by Clemens in Crania Americana (1839), encouraged anthropologists and other researchers to get involved in what would become West Virginia’s most controversial archeological find.

While Clemens did not recoup his investment in the dig, his write-up about the findings made his reputation as a public intellectual grow. Gibson Lamb Cranmer refers to Clemens in his 1902 book, History of Wheeling City and Ohio County, West Virginia and Representative Citizens, as “a ready writer and fluent speaker.” Of particular interest, though, are his descriptions of Dr. Clemens’ workshop “for the production of splints, thermometers, barometers and surgical instruments, besides other apparatus for scientific purposes.”

Knowledge of Clemens’ private workshop and mechanical abilities led David Oestreicher, an independent scholar from White Plains, N.Y., to surmise that Clemens forged the stone in his workshop and planted it on the dig site as an effort to increase interest in the Grave Creek Mound and to encourage prospectors to pay to do their own treasure hunting.

Central to Oestreicher’s hypothesis in a paper he presented to the West Virginia Archaeological Society in 2008 is the discovery of the 1752 book, An Essay on the Alphabets of Unknown Letters that are Found in the Most Ancient Coins and Monuments of Spain. Oestreicher claims that Clemens would have had this book in his library because he was such an engaged reader and thinker. Upon examination of the book, Oestreicher found that the same symbols and errors were found in the inscription on the Grave Creek Stone, which further supports his hypothesis that Clemens forged the stone.

While Oestreicher’s theories have not been substantiated by other scholars, it is commonly accepted by a majority of modern archaeologists that the stone is a hoax. Further complicating the argument, the stone itself has not been seen in decades. All that remains is a photo of the actual stone taken in 1878 located in a collection at the British Museum, four casts of the stone in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History archives and a wax impression of the stone in the National Anthropological Association’s collection.

Lore passed down through the Tomlinson family states that the stone was “given to the Indians” by Dr. Clemens. Tomlinson descendant, Phyllis Slater, “heard that the stone was taken to Arizona,” but so far, it has not publicly resurfaced, despite decades of searching.

“And Never the Twain Shall Meet”

Samuel Langhorn Clemens, who borrowed his pseudonym Mark Twain from riverboat culture (meaning the water was 12 feet deep and therefore safe for passage), was known far and wide as a brilliant teller of tall tales. Although his connections to Wheeling might seem minimal, they read in a sense like some of his stories: humorous, tangled and somewhat unbelievable.

One thing is certain, Wheeling left its mark on Mark Twain. In a letter to his beloved wife Olivia written on the night of his lecture at Washington Hall, he wrote, “Livy darling, it was perfectly splendid — no question about it — the livest, quickest audience I almost ever saw in my life.”

• Christina Fisanick, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English at California University of Pennsylvania, where she teaches expository writing, creative non-fiction and digital storytelling. She is the author of more than 30 books, including her most recent memoir, “The Optimistic Food Addict: Recovering from Binge Eating Disorder.” She has been a Weelunk contributing writer since 2015. Christina is a 1996 graduate of West Liberty University and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She lives in Wheeling with her family.