The tale of Streetcar No. 639 began almost a century ago and is one rife with twists and turns; adventure and neglect; discovery and dedication, notoriety and exaltation. This story begins in Wheeling in 1924 and ends in Maine in 2023. It starts with a streetcar that was quite unique in nature and ends with that same streetcar being the last of its kind. The sole survivor.

When I first heard that a Wheeling trolley was in Maine, my initial reaction was to (obviously) go rescue her from the clutches of the East Coast and bring her back home. Then I read log books, journal entries, Dispatch articles by the Seashore Trolley Museum, and a book that was essentially a love letter to No. 639 and the crew that worked on her.

Hundreds of pages later, I have come to realize that No. 639 belongs where she is, with the people who sacrificed decades of their lives, and tens of thousands of dollars, just to see her whole again. But just because she isn’t in Wheeling, doesn’t make her any less of Wheeling.

As I delved into the history of No. 639, I couldn’t help but notice the incredible parallels between the streetcar and the city herself: the weird, wonderful, and neglectful influence of human nature, combined with the patience, perseverance, and tenacity that eventually reclaimed the car from the crush of time.

No. 639’s Origin Story

Streetcars had been the preferred method of transportation in Wheeling since 1888, when the first electric streetcar embarked on its inaugural voyage from Main St. and 27th1. Since then, trolley design had evolved with manufacturers developing increasingly more efficient models, which is where No. 639 comes in.

The year was 1924. The Cincinnati Car Co. built 21 cars (Nos. 631-651) which had the new, distinctive curved-side design. The curved steel plates were designed to bear most of the weight load, meaning that floor supports were rendered obsolete. These trolleys were a forerunner of later streamlined cars.2

In short, life for No. 639 was good: it was a top-of-the-line streetcar, trolleys were the way of transportation during the time, and Wheeling had plenty of business to supply it. However, as time passed, an enormous curveball was thrown at the trolley system by way of automobile and public transportation development; automobiles became more accessible to the general population, and for those who couldn’t afford one, buses were becoming a more popular mode of public transportation since they were both cheaper and easier to operate and construct. By 1948, life took a sharp left turn for old No. 639 – the trolley has effectively branded a thing of the past, and the city had no more need for it. 3

Fear not, dear reader, this is not the end of No. 639’s story. It is, however, the beginning of a rather strange adventure.

How a Trolley Became a Doctors Office

After No. 639 was officially retired as a mode of public transportation, it was purchased by Dr. Allison K. Walker of Little Hocking, OH around 1950. It was here in Little Hocking that Trolley No. 639 would begin a new journey serving as a medical unit. This chapter of No. 639’s journey is another whirlwind tale, which we will save for another day.

After Dr. Walker died, the trolley “suffered from a decade of benign neglect.”4 In 1957, a member traveling through the Ohio countryside just happened to catch a glimpse of the elusive trolley nestled in the hills. The museum wasted no time in purchasing it from the doctor’s daughter.

Wheeling’s Trolley Saved, Again

After being spotted in the hills of Little Hocking, the Seashore Museum purchased No. 639 and set about the task of bringing her home to Kennebuckport, Maine. The crew organized to carry out the longest over-the-road move for the museum were members Lester H. Stephenson Jr., Ben Minnich, and The Highway Monster, Seashore’s Mack truck-turned-trailer.

Lester documented the entire process in his journal, which is available in this edition of the Seashore’s Dispatch. The dispatch describes the daunting trip to get No. 639 to Maine that began on Thursday, November 21, 1957, and ended over a week later on Wednesday the 27th. During this time Ben, Lester, and The Highway Monster had one hell of a week. It began with cleaning out all the medical supplies left behind in the truck (and one organ – yes, like the kind in church), and was followed by:

A quick and dirty paint job because “the car [was] so awful-looking that those at the museum would reject it immediately if its appearance was not improved”

Dealing with the Highway Monster’s jerry-rigged radiator and air compressor “about 4 times during [the] trip, [the air compressor] plug dropped out and it was a mad dash to stop, secure vehicle and set glove over hole while Ben went back to find [the] plug.”

Braving hazardous road conditions during a Midwest snowstorm.

And even some run-ins with other motorists and local law enforcement.“[A] hot rod driver almost ran into the tail end of truck in Sisterville, WV. Coming like hell and didn’t see it till almost too late, but he ran up on sidewalk and avoided it. Got a motorcycle cop all excited in Weirton, W. Va… he told us to be sure and tell headquarters next time we thru with big load (Next Time??) Also got stopped by a New York State trooper who evidently had nothing better to do… He couldn’t find anything wrong with our papers so he dug deeper and finally read us out for not keeping a driver’s log on truck as required by NY State law (not ICC). All in all it was an interesting trip.”

After nearly a week of shenanigans, No. 639 finally made it to her new home, where she would become the first-ever steel trolley to be fully reconstructed inside a museum. 5

A Labor of Love

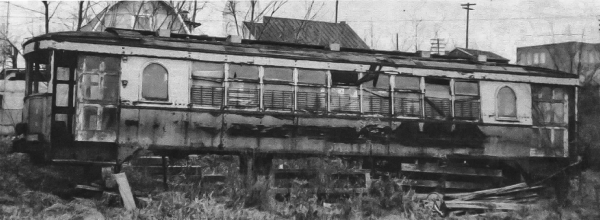

Although she was brought in during the winter of 1957, work did not begin in earnest on No. 639 until 1974. During this 17-year gap, parts were gathered throughout the country to replace and rebuild the body of the trolley, but No. 639 was largely regarded as “an eyesore… an old orange hulk with little or no future.” 6

Enter Jim Schantz, who “never lets the size of a project faze him.” 7 Jim collected photos of trolleys from 639’s fleet from Bill Gwinn a veteran Wheeling motorman who spent the better part of his career transporting the people of the Ohio Valley on his beloved trolleys. After studying the photos, Jim and the team began to start the incredibly arduous process of putting her back together.

Why arduous? Because although 639 was referred to as a ‘rubber stamp’ trolley, due to the prevalence of the curved-side design in the 920s – 1930s, our girl was different. One source explains that “most Cincinnati Curved-Sides were required with the firm’s own ‘arch bar’ trucks… for some unrecorded reason, the cars built for Wheeling were one of only two orders of Curved-side cars which deviated from this practice [resulting in] a rather rare and odd design.” 8

Using whatever he could salvage from No. 639, Jim began the most complete rebuild of a trolley the museum had ever undertook. Relying solely on volunteer hours, or ‘sweat equity’, and fundraising efforts, work began.

Over the next three decades, No. 639 would be a community service project for countless people, and a passion project for a handful of men. Jim Schantz, Donald Curry, Lester Stephenson Jr., Dave Garcia, and Danny Cohen were just a few who were absolutely committed to restoring No. 639 exactly as she was built, even if that meant working harder and not smarter – like recreating the chair frames from steel, the original material, instead of wood.9

The attention to detail that was paid to restoring No. 639 is truly astonishing; you can find information on the journey to her renaissance from 1974 – 2002 here, and 2003 – 2006 here. A very quick and incomplete rundown of the exhaustive process includes: finding the right linoleum (it was ‘Battleship’), creating new interior framework, completely re-wiring all the electrical components, scouring the country for parts (which came from Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and even England) to remake the engine and mechanical components, creating contoured heaters, custom-made window sills, seats, pulleys, push-buttons, finding the right fabric, etc. (9,10)

In addition to the laborious hunt for parts and physical restoration, sourcing funds was something that had to also be consistently done throughout the decades. There were several years where no work could be done, and no parts could be purchased, due to lack of funding. During these years Jim was a driving force to complete the work on No. 639, even writing a book in 1993, with 100% of the proceeds going towards funding the restoration. (9,10)

Schantz wrote another book in 2020, Traction in the Panhandle: Wheeling Transit in the Curved-Side Era, with Frederick J. Maloney. Schantz dedicated this work to Bill Gwinn, the Wheeling motorman whose photo collection of the curve-side trolley allowed Schantz and crew to re-create No. 639.11 Talk about a class act.

READ MORE: The Streetcar Trolleys that Changed Wheeling

The Last One Standing

On August 22, 2009 No. 639 made her inaugural run on the Seashore Trolley Museum’s 1.5-mile track. And they made an event out of it. Commemorative tickets were given to everyone who worked on the trolley, and the public was invited to see the sole survivor of the Wheeling streetcar fleet make its debut. 12

Jim Schantz addressed the crowd during the ceremony, unveiling a brass plaque dedicated to two of the men who put their hearts and souls into finding and restoring No. 639. The first was Frederick J. Perry, “a talented steelworker and a mechanical wizard.”13 The other was Dwight Benton “Ben” Minnich, who picked up No. 639 from a hillside in Little Hocking in 1957 and continued to advocate for her restoration until his passing.

Although Ben was not around to see No. 639 restored to her former glory, his partner on that madcap journey, Lester H. Stephenson, Jr. was. 52 years later it was Lester behind the wheel when No. 639 was finally ready for her first ride around the mainline track.

The parallels between No. 639’s journey and the city of Wheeling are not lost on me. Regardless of where she spends her time, No. 639 is pure Wheeling through and through – once great, but she fell upon hard times until a myriad of dedicated people saw her worth and potential. And with their vision, passion, patience, and persistence she was rebuilt and is thriving.

If you, like me, now feel weirdly bonded to this trolley in particular, you can go visit her at the Seashore Trolley Museum (it re-opens on May 6). While the story of the Wheeling Streetcar No. 639 is unique, it can’t be the only piece of Wheeling history that landed in an unlikely place. If you know of any others, let us know about it in the comments. We’d love to share their stories as well.

• Haley Steed has lived in Wheeling for the past 9 years. Before moving to Wheeling, she lived in Columbus, OH where she graduated with a BA in Comparative Cultural Studies from Ohio State University. Haley also earned an MS in Marketing and Communications from Franklin University. She has held multiple marketing positions for 10+ years, with experience in PR/media relations, internal communications, marketing campaign strategy + execution, SEO, branding, content creation, digital analytics, and graphic design. Haley currently serves as an AmeriCorp member at Wheeling Heritage. Haley has one human named Vida, two cats named Hank and Squigs McAllister, and is currently manifesting that her one-day husband’s name will be Jeffrey Goldblum.

References

1 Emma Wiley, “All Aboard!: The Streetcar Trolleys that Changed Wheeling” Weelunk, April 14, 2021 https://weelunk.com/aboard-streetcar-trolleys-changed-wheeling/

2 James D. Schantz, Frederick J. Maloney “Traction in the Pan Handle: Wheeling Transit in the Curved-Side Era”, 2020.

3 Emma Wiley, “All Aboard!: The Streetcar Trolleys that Changed Wheeling” Weelunk, April 14, 2021 https://weelunk.com/aboard-streetcar-trolleys-changed-wheeling/

4 “West Virginia Day at Seashore” Press Herald, June 20,2021. Accessed January 18, 2023 https://www.pressherald.com/forecaster/forecaster-calendar/?_escaped_fragment_=/show/?start=2020-03-06#!/details/West-Virginia-Day-at-Seashore/9188661/2021-06-20T00

5 James D. Schantz, Frederick J. Maloney “Traction in the Pan Handle: Wheeling Transit in the Curved-Side Era”, 2020.

6 Unknown, “The Wheeling Car Needs Your Help!” Seashore Trolley Museum Dispatch, Jan/Feb 1967.

7 Donald G. Curry, Seashore Trolley Museum Dispatch, Sept/Oct 1974.

8 James D. Schantz, Frederick J. Maloney “Traction in the Pan Handle: Wheeling Transit in the Curved-Side Era”, 2020.

9 New England Electric Railway Historical Society, Seashore Trolley Museum Dispatch, 1993-2002

10 New England Electric Railway Historical Society, Seashore Trolley Museum Dispatch, 2003-2006

11 James D. Schantz, Frederick J. Maloney “Traction in the Pan Handle: Wheeling Transit in the Curved-Side Era”, 2020.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.