Wheeling has a reputation for being a country music hub. So much so that along the way the city earned the nickname “Little Nashville.” I grew up two doors down from Wheeling’s country music legends Doc and Chickie Williams. I have many fond memories of visiting their house where they often hosted visiting musicians to jam, make recordings, and feast on Chickie’s delicious food. The Capitol Music Hall was frequented by me and the couple’s grandson and my childhood buddy Andy McKenzie. There we witnessed the thriving music scene first hand. Many years later while driving in Wheeling I was pleased to see the stretch of I-70 in Elm Grove named after the royal music couple in tribute to them and their contributions. As a jazz musician and enthusiast I thought to myself, “does Wheeling have any jazz musicians from our past that deserve to be celebrated and remembered in this way?” As it turned out, we definitely do!

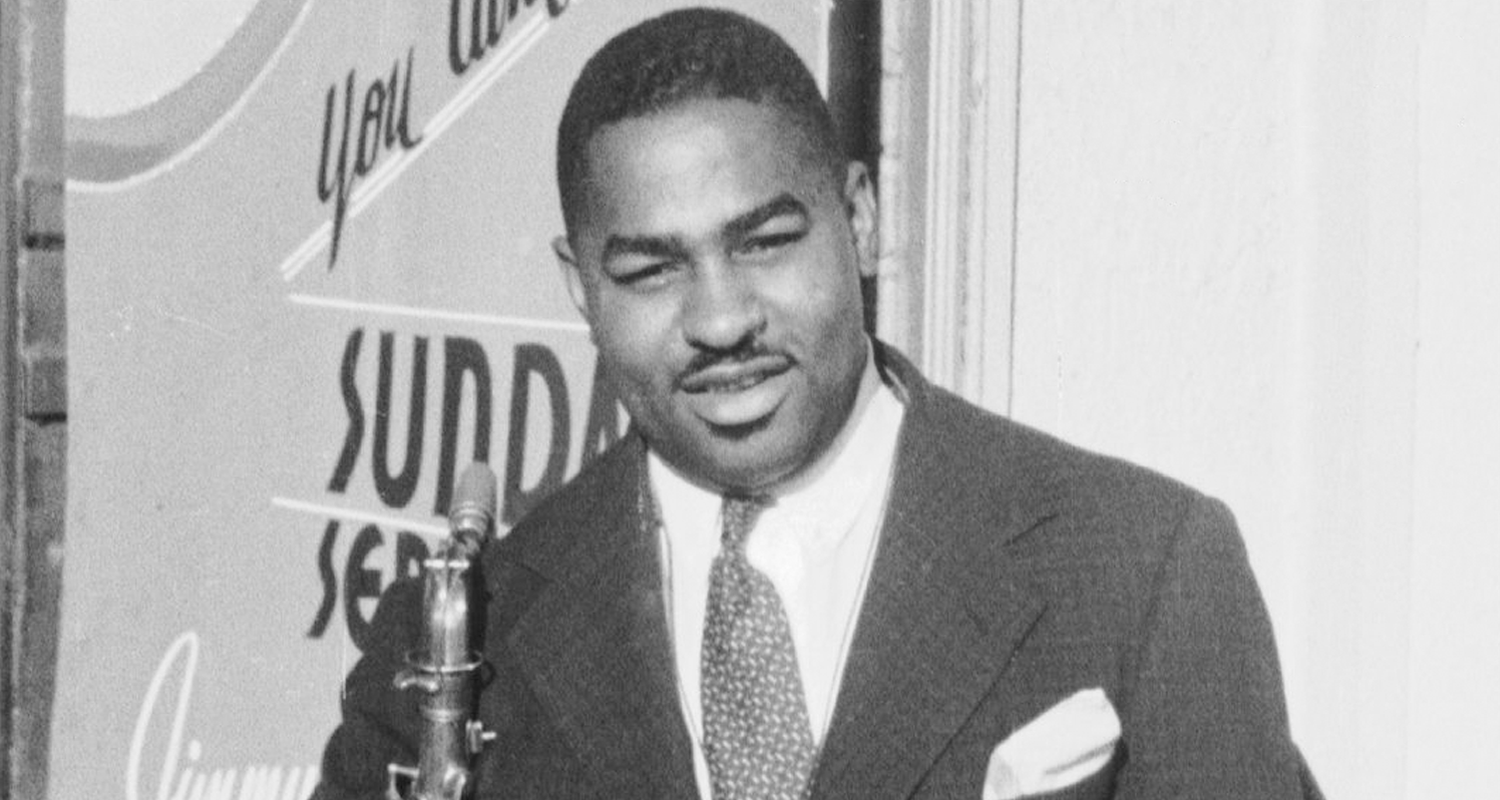

One of the most important and outstanding tenor saxophonists of the swing era of jazz music was Wheeling’s own Leon “Chu” Berry. Berry took up the saxophone at a young age after being inspired by the great tenor man Coleman Hawkins. Berry went on to model his own playing after Hawkins. Hawkins would later be quoted as saying “Chu was about the best.” Consider also that alto saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker, father of 20th century modern jazz, named his first child Leon in tribute to Berry who was 14 years his senior. Bebop pioneers like Charlie Parker and his pal trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie would most certainly have heard Berry up close and personal in the early 1940s at the now legendary Monday night jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse in New York City which led to the development of bebop.

A graduate of Lincoln High School, Berry made his mark and name as a top-tier tenor player and featured soloist with the cream of the crop of the 1930s and 1940s big bands. He was featured in the bands alongside many legendary jazz luminaries such as Benny Carter, Fletcher Henderson, Mildred Bailey, Teddy Wilson, Billie Holiday, Lionel Hampton, and Cab Calloway. Berry, like the other standout tenor players of the era, was a masterful ballad interpreter, but he was also known for his virtuosic technique and ability to play at fast tempos. Berry also made important contributions to the genre as a composer; most notable with the 1936 hit song Christopher Columbus which he wrote for the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra and was the band’s last major hit. The riffs and themes of the song were later used in the Benny Goodman showstopper Sing Sing Sing.

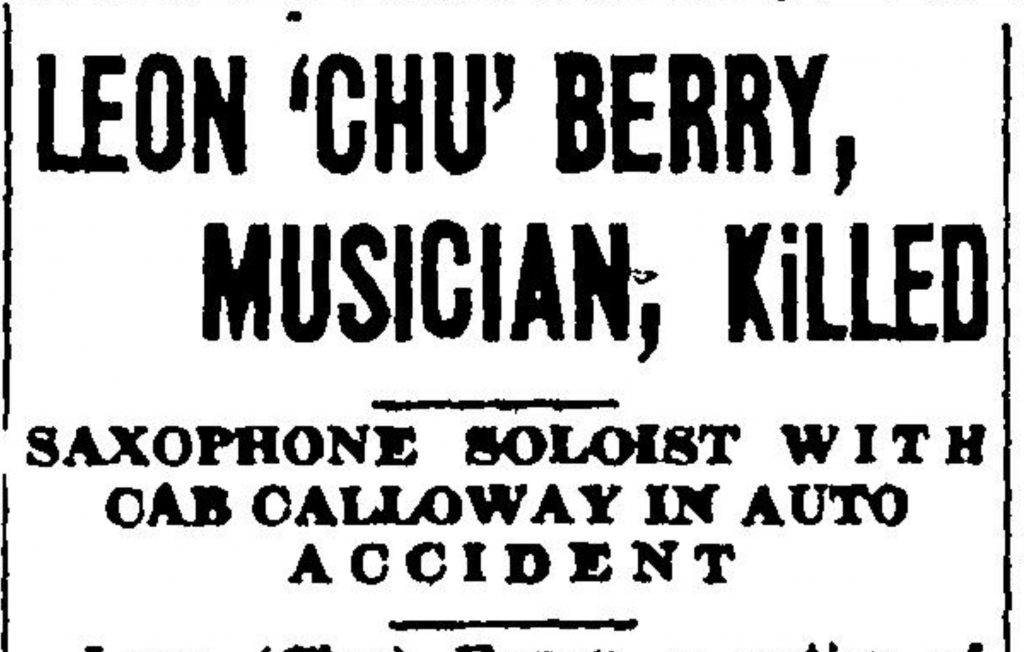

So why then isn’t Leon “Chu” Berry” a household name along with the other tenor sax giants of the era like Ben Webster, Lester Young, and Coleman Hawkins? Sadly the answer is that while touring with Cab Calloway’s band he was fatally injured in a car crash in Conneaut, Ohio. He passed away on Oct. 27, 1941 from injuries sustained in the accident. Berry and Calloway were close friends and Berry was considered the greatest musician in his orchestra. According to a 1941 article published in the Afro-American (Baltimore), “Cab received news of Berry’s death while playing before 5,000 people in Toronto, Canada, where the band was en route when the accident occurred. He worked four hours without letting the band know of Chu’s death. He stopped the band twenty minutes before the close of the engagement and made the announcement, after which the band played God Save the King.” Calloway flew to Wheeling from Rochester, NY for the funeral where over a thousand people were in attendance.

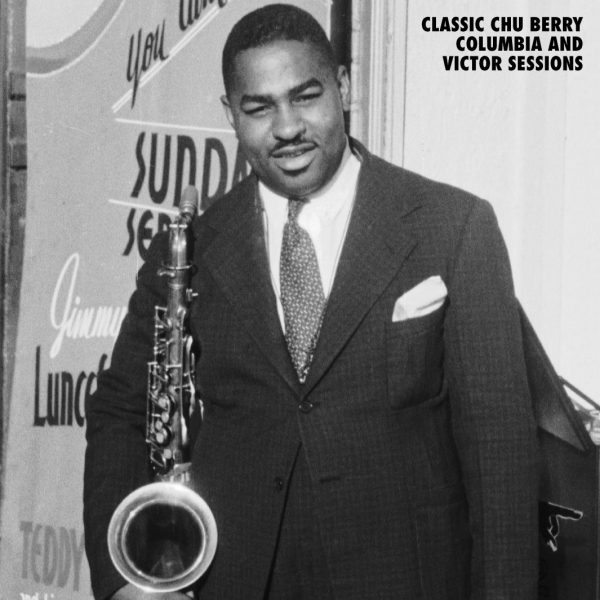

What would have been in store for Berry and his music if it were not for his untimely death? Would he have ascended to the pinnacle of jazz royalty next to his contemporaries Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young? Or given his connection and influence on the early development of bebop, might he have been even further celebrated as a creator of Bebop along with Gillespie and Parker? One can only wonder. What we do know is that his contributions to the music are vast and although we mourn his untimely departure, we can appreciate and experience the many recordings he left for the world. Lucky for us, Berry was incredibly active in the recording studio for the majority of his career and as a result, his music will endure forever.

I truly hope that music lovers in the Ohio Valley and throughout the world will discover or re-discover the many musical masterpieces left to the world by Wheeling’s own Leon “Chu” Berry. Who knows, maybe one day a statue of the hometown saxophone legend might be erected here, like the Charlie “Bird” Parker memorial statue in Kansas City, as a tribute to one of the greatest of all time.

Suggested Listening:

Christopher Columbus – Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, 1936

This first example is one of the most popular riff tunes from the Swing Era.

Chuberry Jam – Chu Berry and his Stompy Stevedores, 1937

A really fun track with lots of soloing and a tongue-in-cheek nod to Ragtime.

Maelstrom – Chu Berry and his Stompy Stevedore. Sept., 10 1937

This piece is another obvious precursor to Benny Goodman’s Sing Sing Sing.

I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You – Cab Calloway Orchestra, 1940

Berry plays beautifully on this 1940 ballad recording. Dizzy Gillespie sits in the trumpet section of the orchestra.

This speedy number is what the musicians call a “burner.” You can hear Berry’s fluency and technical prowess on this up-tempo number.

References

1. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/biographies-leon-chu-berry/2683

2. Scott Yanow allmusic.com Charlie Parker Biography https://www.allmusic.com/artist/charlie-parker-mn0000211758/biography

3. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/biographies-leon-chu-berry/2683