It could be said that Wheeling is a town with theatrical flair and giving hearts. These days, Wheelingites gather funds to support worthy causes by hosting steak frys, raffles, and charity dinners, but in 1922 they had a different idea– hosting a Womanless Wedding! Hoping to raise money for childhood hunger, Wheelingites latched on to this trendy idea and made a huge splash. The success of the 1922 Womanless Wedding at the Court Theatre reverberated in the area, with copycat productions being staged for the benefit of various causes by groups on both sides of the river.1

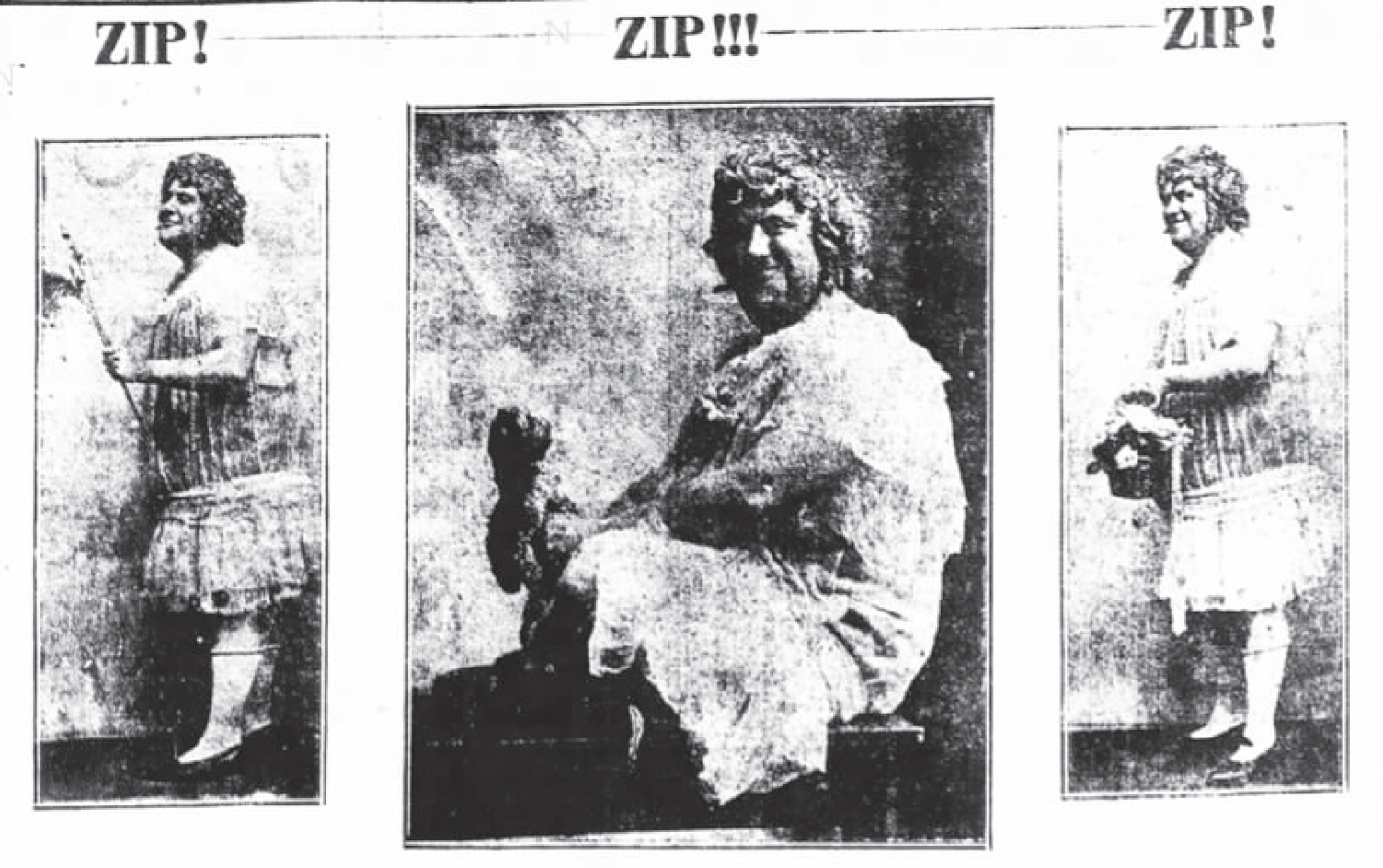

What is a Womanless Wedding, exactly? Womanless Weddings were theatrical productions in which men played all the parts. Sounds a bit like the days of Shakespeare, right? Kind of. Where women used to be forbidden from appearing on stage (hence men playing all parts in a Shakespeare-era play) the Womanless Wedding omitted women for the sake of comedy. The hilarity of the enterprise relied on a handful of Wheeling men who didn’t mind slipping into a dress for the good of the community. The players were usually prominent city residents, or members of social or civic organizations.

The Woman Behind It All

It’s understood that the phenomenon of the Womanless Wedding appears to have started in the south, with productions being staged as early as 1917 in Houston, but the craze soon spread.2 But who was responsible for importing this theatrical delight to the Friendly City?

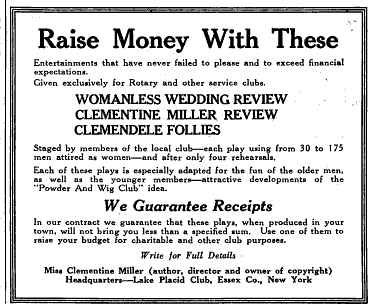

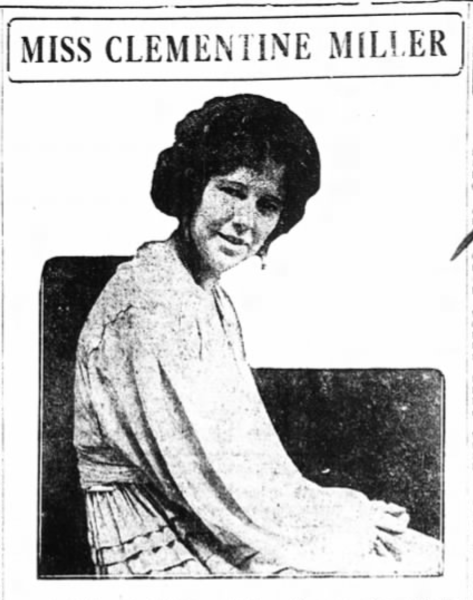

Enter: Clementine Miller. The play’s author, Clementine Miller even came to Wheeling to assist in the costuming, direction, and staging of the men’s valiant efforts. The group only practiced twice before their debut! A “true daughter of the sunny south,” Miller “won a hearty endorsement from the Wheeling people” in her short stay in the city.

The reviews in the local papers were whole-heartedly positive, with reporters dwelling on the details of the lavish costumes and lively musical numbers “of unusual merit.” While it appears that some actors pitched their own voices up to sing a song or two, a case of covert lip-synching caught the audience by surprise– Fred Fox’s “beautiful soprano solo” was actually sung by Miss Anita Wagner, who was hidden from the audience’s view. 3

“Once on the stage, there is no way to escape” quips the Wheeling Register’s reporter. The one-act comedy had no change of scenes or curtain. The majority of the production consisted of actors being introduced to the audience and ushered onto the stage. Once the befrocked men made their debut, “each girl was there for the night.” The reporter marveled at the lengths the actors went to commit to the bit. It was noted that the mustache of at least one man had disappeared for the sake of the production– whether it was shaved off or simply concealed with theatrical makeup was not revealed.4

The culmination of the brief yet raucous production was, of course, the wedding ceremony. “The wedding ceremony was pulled off as a grand finale, the company unmasked– or to be exact– unwigged.” The Womanless Wedding was so successful the reporter mused that it was “doubtful [that] a Wheeling crowd has enjoyed itself so hilariously since the day the armistice was signed.”5

The Rise and Fall of Womanless Weddings

The success of Wheeling’s first Womanless Wedding did not go unnoticed by the surrounding community. Just five days after the curtain fell on the Court Theatre stage, the Americus Club of Bellaire announced their intention to hold one. The revue was a popular fundraising model for local organizations into the 1930s and beyond, with various churches holding their own weddings. Local Women got into the wedding business, too. Women’s groups like the Warwood Ladies’ Aid and the Elm Grove Dames of Malta tried their hand at “Manless Weddings” in the 1930s.

Over the years, the popularity of the “Womanless Wedding” tapered off. This could be a result of a combination of factors– the rise of alternative fundraising strategies (hello, tip boards), the decline of the theatre as a primary entertainment source, and the acceptance of same-sex marriage. The humor of Womanless and Manless weddings hinges on the fact that they are “rituals of inversion.” Like Mardi Gras or Halloween, costumes are donned which allows the individual to transcend their “everyday” identity. This playful environment allows for a critique of social norms in a way that still shows how important they are. Rituals of inversion are not a threat to everyday life, but rather a unique way of celebrating it. In fact, they often highlight what is most important to a community by lampooning it.6

References

1 “Bellaire to Have Womanless Wedding,” The Wheeling Register, June 22 1922, page 8. Wheeling, West Virginia.

2 Linton Weeks, “When ‘Womanless Weddings’ Were Trendy,” NPR History Dept., June 16, 2015,https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/06/16/413633022/when-womanless-weddings-were-trendy

3 “Boys Will Be Girls When The Womanless Wedding Takes Place,” the Wheeling Register, June 16, 1922. Page 6. Wheeling, West Virginia.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Weeks

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.