Editor’s note: Of all the forms of spirituality practiced in Wheeling, perhaps the least understood is that of the various orders of nuns who have served in the city since the 1840s. The Sisters of St. Joseph, one of two remaining communities here, opened their archives and hearts to share glimpses of their story with Weelunk readers.

When the first rounds of Roman Catholic nuns arrived in Wheeling in the 1840s and 1850s, it was already an industrial boomtown full of great wealth, poor immigrants and an ever-widening political divide over the issue of slavery.The Civil War that soon began to rage didn’t make anything easier.

EARLY DAYS, LONG DAYS

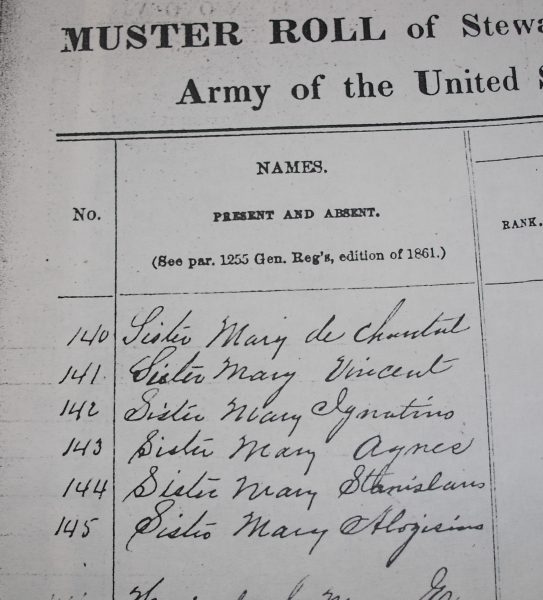

Little more than a decade into running the freshly chartered Wheeling Hospital, the Sisters of St. Joseph got an unexpected knock on the door in spring 1864. Officials from the city and the Union Army wanted to enlist them as military nurses and to rent their 15th Street facility as a full-blown military hospital.

Private patients and orphans were relocated as both prisoners of war and casualties began to arrive, some of them “prostrate with disease” and others gravely wounded, according to a community journal kept by Sr. Mary de Chantal Keating. (Journal entries are among several records provided for this article by Margaret Brennan, local historian and former Sister of St. Joseph.)

“There were so few of us, it was necessary to work almost without stopping,” de Chantal Keating wrote, noting she once left a long day in the operating room only to find the other sisters sleeping on the floor in the chapel with sacks of leaves for pillows. They had given their beds to soldiers.

The crisis reached its most difficult point on the evening of July 26, 1864, when the entire hospital was commandeered as 200 wounded and sick soldiers arrived without warning. “They were sent up as fast as ambulance could be provided for them,” de Chantal Keating wrote. “We laid them on the floor on rows of blankets, supplied them with immediate requirements and left them to repose as they might after a toilsome journey.

“Some among them are great sufferers; we are busy enough but can do a great deal to soothe their miseries.”

CHANGE, MORE CHANGE

Perhaps no one has a better perspective on how convent life has changed over the decades than Sr. Gabriella Wagner. At 101, the Mount St. Joseph resident is one of the oldest living nuns in the Sisters of St. Joseph community.

When Wagner entered convent life after her junior year of high school, nuns were still wearing full habits, had not even a dime of spending money and were summoned to morning prayers by a bell. Over the years, she reduced down to a modified habit in the 1960s, then no habit at all. She acquired two college degrees, an alarm clock and some serious skill at making stuffed animals for fundraisers.

And now, long retired from both her last math and science teaching position at Wheeling Central Catholic High School and the business office at Mount St. Joseph, she has a room of her own, with hand weights and a devotional stored close to her chair. She attends Mass most days on-site, even though her hearing is limited. She prays alone and whenever she likes.

“I don’t know why they want to build me up,” she joked of the weights, part of her physical therapy. “Do they want to make me live to 110?”

Not that she would necessarily mind. The Triadelphia-raised Wagner said a nun’s life was the right one for her, something she knew when she was in second grade.

“I went to St. Vincent’s to school and often the parish priests were there, and they would say, ‘How many are going to be sisters? How many are going to be priests?’ and I just raised my hand.

“If I had to do it all over again, I would do it, and I would be happy,” Wagner said.

HOLDING STEADY

She’s not the only one. Sr. Jennifer Berridge, formerly a medical and social worker from Cleveland, felt the same call. Just later in life.

Berridge, now 45, entered the convent in 2016. She is on the way to making her first, temporary vows this summer. Permanent vows would come three years after that.

While her devotion is similar to Wagner’s, her life has unfolded very differently. One of only two siblings — as opposed to Wagner’s 13 brothers and sisters — Berridge lived a typical American existence until mid-life.

While working at an Ohio hospital, she was approached about the possibility of convent life and something clicked for the cradle Catholic. After a year of thinking about it, she left her secular job and solo apartment to head to Wheeling.

She now lives with sisters who are decades older than she, joining them for nightly meals and prayer, but otherwise living a life that isn’t entirely removed from the one she left behind.

The downtown-based sisters — who live in a portion of the same building that once housed the Civil War soldiers — keep their own daytime schedules and do their own morning prayers, for example. Berridge uses her social work training to work in pastoral care at Serenity Hills Life Center, an addiction-recovery site for women.

They wear street clothes. Indeed, on the day of this interview, Berridge was wearing a T-shirt with a scriptural reference, pants and riding boots.

They check in with each other via texts and WhatsApp.

Not everything is the same, though.

“I didn’t really have to report to anyone about how I spent my time,” Berridge said of her secular life. “(Now,) we’re very intentional about community life, living out our lives together much like a family. … The same frustrations families have, we have. We just talk about it.”

Also, while today’s nuns do have some personal money should they want to have coffee with friends or such, it comes from a monthly budget. “We have one checkbook for the house,” Berridge said. “We’re conscious about what’s coming in and what’s going out.”

She has also become acutely aware of who is coming in and going out.

“There’ve been quite a few deaths since I’ve been here,” Berridge said. “I read a book that said young nuns get good at grieving. I didn’t want to get good at grieving, but I have.”

Berridge, who believes the community will look very different in even five to 10 years, said they are in the process of “right-sizing buildings” and looking critically at what they have to work with and what they actually need. This is a continuation of a decades-long process of turning many facets of community life — such as teaching and hospital duties — over to secular employees who share the order’s values.

“Our goal is to do what we can with whoever and whatever we have,” Berridge said.

A CITY WITH NO NUNS?

Brennan the historian agrees with Berridge that this long history of both constant presence and change will shift again in the next decade or so. It’s a question of numbers. With few American women taking religious vows in recent decades, Wheeling is running out of nuns.

“I would think that (no remaining sisters) would be a possibility down the road because of the trend locally and nationally,” Brennan said, noting most area priests are now from either India or Africa.

There is also a precedent for community comings and goings, she said. Nuns from the Visitation order, which most recently ran Mount de Chantal Academy, came in the 1840s and stayed until that school closed in 2008.

The few remaining Visitation sisters then relocated to Georgetown Visitation Academy in Washington, D.C., Brennan said. That community includes a “great infirmary” that Brennan noted at least some of the sisters soon needed.

Wheeling was also home for a time for a Carmelite order of nuns who operated a cloistered monastery near the current St. Michael complex. Dwindling community population also caused their disappearance, Brennan said.

Today, in addition to 35 or so Sisters of St. Joseph still living in downtown Wheeling and at Mount St. Joseph in the city’s outskirts, Brennan said there are a handful of sisters from yet another order — Good Shepherd — in Woodsdale/Edgwood.

While the Good Shepherd sisters could follow the Visitation sisters’ example and eventually join with another community, the Sisters of St. Joseph are still taking in sisters from other parts of their multi-state order. While these imported sisters are generally coming into Mount St. Joseph’s infirmary, there is still a Wheeling presence, noted Rose Mathes, coordinator of community life at Mount St. Joseph.

“Even though the median age of the Wheeling sisters is high, the mission of the Congregation of St. Joseph — loving unity and outreach to neighbors in need — will continue via (the) sisters, associates and employees who will continue to fund important projects through several foundations,” Mathes said.

Brennan believes all of the various sisters’ work will carry out in a less tangible way, as well.

“These women who helped build the fabric of Wheeling starting in the 1840s and 1850s have provided a dimension of spirituality,” Brennan said, calling them the city’s “designated pray-ers.”

“Prayer is always good.”

• A long-time journalist, Nora Edinger also blogs at noraedinger.com and Facebook and writes books. Her Christian chick lit and faith-related non-fiction are available on Amazon. She lives in Wheeling, where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household.