Editor’s note: Our series, Working Our Way Back to You, profiles Ohio Valley natives who have left town but returned to the community that created them. In today’s story, writer Phil Gable introduces us to Gerry Reilly — who isn’t actually a native, but maybe he should have been.

Editor’s note: Our series, Working Our Way Back to You, profiles Ohio Valley natives who have left town but returned to the community that created them. In today’s story, writer Phil Gable introduces us to Gerry Reilly — who isn’t actually a native, but maybe he should have been.

Stay with me. Here’s a slight cosmic irony. If my recollections of local history are correct, growing mining interests led a certain Earl W. Oglebay to move to Cleveland in 1881. Oglebay would continue to divide his time between Cleveland and Wheeling, but he would periodically return to Waddington Farm to experiment with the latest in scientific farming methods.

The inverse was true of Gerry Reilly. Born in Cleveland in 1956, Reilly’s professional development would lead him to call Wheeling home very early on in his life. And even after he moved away, he would still return. (I’m getting ahead of myself again.)

The point is this: often, the place where you hang your hat and the place where you leave your heart might be two different places. And if your home is Wheeling, then your home is often complicated.

So how did Gerry Reilly find his heart in Wheeling? I thought you’d never ask!

INTERTWINING PASTS

Reilly’s connection to the town came early. Born and raised in Cleveland, Reilly graduated from John Carroll University in 1978 and quickly moved on to graduate studies at Case Western Reserve, where he completed his master’s degree in history and museum studies.

Even there, while working as a curatorial assistant, the history around Reilly was pointing to his future — his time spent working in the Cleveland History Center familiarized him with the story of Earl Oglebay’s rise to fame as one of the region’s leading mining industry magnates.

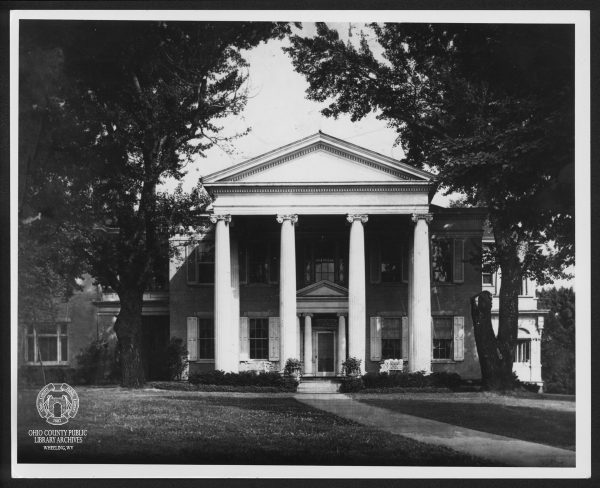

Shortly afterward, Reilly hired on as curator of collections for the Oglebay Institute Mansion Museum.

In recalling his first day on the job, Reilly chuckles. Courtney Burton, Oglebay’s grandson, arrived unannounced to the museum that day, intent on locating a portrait of Earl Oglebay’s first wife in art storage.

As Reilly frantically scrambled around an unfamiliar environment to find the painting, a perplexed Burton probed, “Why don’t you know all this?” To which Reilly explained, “I just started!”

If Reilly initially seemed a tad overwhelmed, the predicament was understandable. The museum held over 20,000 objects at that time.

“My job was to organize that,” Reilly explained. “When I started, we had mostly exhibits that we would rent.” These rented exhibits also needed to make sense in the context of the collections that the Mansion Museum owned, which included large quantities of glass and pottery.

As the museum grew and developed, so did Reilly. In 1993, when the Carriage House Glass Museum was created, Reilly oversaw the transfer of thousands of pieces of glass to the new location. Premier amongst these pieces was the Sweeney punch bowl — a 5-foot-tall, 225-pound punch bowl known to be the largest piece of cut lead crystal in the world. Reilly’s eyes twinkle as he describes how his team lugged the bowl into its new location on a Sunday morning to avoid the intrusion of rubberneckers.

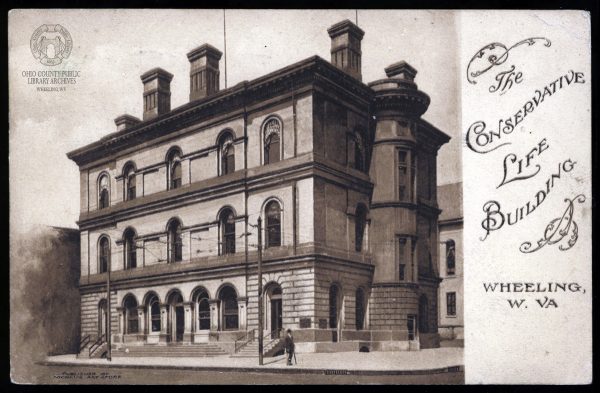

As time went on, another career move immersed Reilly even more deeply in Wheeling history. In 1996, Reilly would become the director of West Virginia Independence Hall, a position he would hold for 10 years. Reilly reflects, observing that “at the time, there wasn’t a whole lot of programming there … one thing we didn’t have at the time was an exhibit that explained West Virginia statehood.” And so, for a solid decade, Reilly labored to change all of that too.

THE BUSINESS OF HISTORY

So why did Reilly leave town after embedding himself in Wheeling so deeply? “If you want to move on, you have to leave,” Reilly explained.

Museum jobs are hard to find, regardless of where you are, which makes careers in this field rather tricky. And so, while Reilly recalls, “I can’t say that I was eager to go,” the demands of career development had him “looking for a change.”

A position opened up for a site manager at the Lanier Mansion State Historic Site in Lanier, Indiana, and Reilly took the leap. If he was looking for a change, he certainly got it.

“When I moved, it was a bigger anxiety moving to a new place,” Reilly recalls. There’s a psychological complexity to “leaving the place you’ve been for 20 years.”

Bigger professional challenges accompanied the geographical ones. Reilly became the eastern regional manager for state historic sites in addition to his role as the Lanier Mansion site manager.

“It wasn’t as prestigious as it sounds,” Reilly demurs. However, he soon found himself managing budgets, developing programs and becoming more involved in the community — no small task for a site that Reilly soon realized was “the largest tourist draw in Madison, Indiana.”

Reilly’s dual-hatted position required him to operate at multiple professional levels. First, there was the work of developing interpretive plans for exhibits — “What are the stories we’re going to tell, and how are we going to tell it … which room should we tell which story?” Reilly also found himself managing personnel issues; employee performance reviews soon became his wheelhouse, not his supervisor’s. And then there was the work of preserving exhibit integrity — no small source of frustration for Reilly.

“They took the ropes down, and people are able to walk wherever they want!”

“They took the ropes down, and people are able to walk wherever they want!” — Gerry Reilly

As we talk, the removal of the ropes at the Lanier Mansion come to symbolize frustrations Reilly had over the lack of professional scruples he found at the Lanier Mansion. You see, one doesn’t just “do” history. These relics, totems, writings, artifacts — all the fragile emblems of our ancestral story — they vanish or fade or crumble. Losing them means we lose a part of ourselves.

The problem was, that’s not how the team at Lanier Mansion saw it. Where Reilly saw a need to protect and preserve a perishable resource, the Lanier staff and leadership around him labored to “Disneyfy” the historical site into a cash cow — amusement now took priority over historical preservation. The logic, according to Reilly, was that “if they become more entertaining, they’ll be able to compete for the recreational dollar.”

For Reilly, it was time to move on. The department was reorganizing. Reilly resigned. Why stick around to watch them pave paradise to put up a parking lot?

CARING FOR HISTORY

When I ask Reilly why he came back to Wheeling in particular, the answer was simple — “The people were friendly!”

It turns out that Reilly’s new boss — Christin Byrum, director of museums for Oglebay Institute — was an intern at the Oglebay Mansion back when Reilly was around the first time. He already knew the team, and they knew him.

Professionally, Reilly really was coming home: “I knew everybody already, it was comfortable, it was still in the museum field.”

However, this time, Reilly — as assistant director of museums — was bringing new skills to the table, to include handling purchasing, managing the budget and all of the “day-to-day running of the place.”

The irony is that even when Reilly was living in Lanier, Indiana, he couldn’t quit Wheeling. “I come back every year for Oglebayfest,” recalls Reilly. Over time, these little pilgrimages expanded to include more and more extended family — siblings, their spouses, nieces, nephews. It was a very Wheeling thing to do, these periodic retreats to Waddington Farm.

There’s something unique about the friendly city that keeps Reilly here in the valley.

“I think Wheeling has one of the most interesting histories of any town in the country, especially for its size,” he muses. “Wheeling had all these unusual things happen.”

Reilly rattles off the shortlist. The battles of Fort Henry. The National Road. The B&O Railroad. The Wheeling Suspension Bridge. The Civil War. Walter Reuther. Joe McCarthy’s anti-Communist movement.

For Reilly, Wheeling doesn’t need to reinvent or Disneyfy itself to entertain others. When it comes to weird and wonderful history, Wheeling is flush. One simply needs to protect the artifacts and let those pieces tell you their story.

Having chatted with Reilly about Wheeling history, one question was left in my mind. What about Wheeling’s future? Reilly is optimistic.

“There are efforts to reinvigorate the town,” he enthusiastically observes. New leaders are getting involved. (Show of Hands, anyone?) “I’m looking forward to them reinvigorating the town and reinventing itself.”

What’s more, Wheeling’s rich history represents one of its greatest resources for the future — “all this great history, we can use those stories.” Without a doubt, Reilly’s history with Wheeling history brought him home.

And that is how Gerry Reilly worked his way back to you.

• Phil Gable is a psychologist, veteran and Army Reservist with a history of one deployment to Afghanistan. Despite growing up in Kennesaw, Georgia, he likes to think of himself as having “married into” the Ohio Valley where his wife grew up. He is a graduate of Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia State University and Fuller Theological Seminary, where he completed his doctor of philosophy in clinical psychology. When not shamelessly navel-gazing or sipping bourbon, he likes to pursue hobbies such as writing, reading and running.