By Earl Nicodemus

Weelunk Contributor

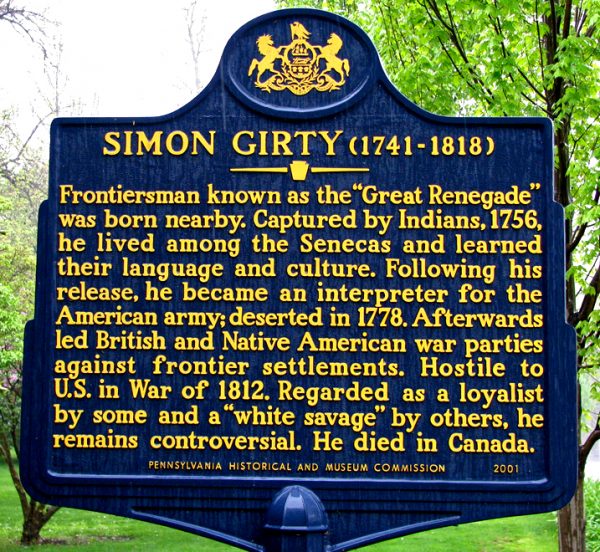

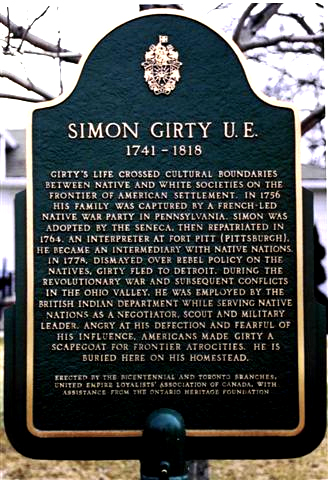

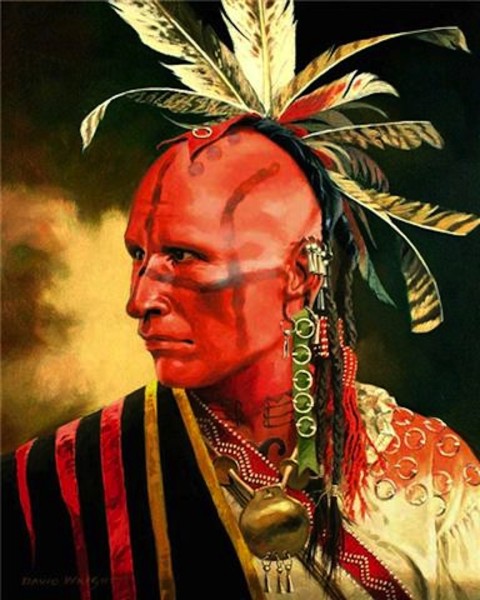

Even though I am a storyteller rather than a historian, I have attempted to find out the real story of Simon Girty. Other than Benedict Arnold, no other individual associated with America’s struggle for independence has been as maligned as Simon Girty, who was known as “The White Savage,” “The White Renegade,” and “Dirty Girty.”

Places in three states and Canada are named after Simon Girty, including Girty’s Point Road near West Liberty. Some of the eyewitnesses who were present during the Indian and British attack on Fort Henry on Sept. 1, 1777, reported that Simon Girty had led that attack even though he was serving in the Pennsylvania Militia at Fort Pitt at the time! I hope you enjoy this mostly true storyteller’s version of the life and times of Simon Girty.

Simon Girty Jr. was born in Harrisburg, Pa., in 1741. He was one of four brothers. Mary, their mother, was English. Their father, Simon Girty Senior, was a Scotch-Irish pack horse driver and Indian trader. In those days, the trails were not good enough for wagons, so anyone who wanted to move freight had to haul it on the backs of pack animals. Pack-horse drivers were a hard-working, hard-drinking, hard-fighting breed of men. Girty Senior fit that mold perfectly. Girty Senior was on the road for long periods of time, so his wife, Mary, and the boys were often left to look after themselves.

Sometimes, the Indian trading encounters were drunken events during which fists were also traded. During one such drunken brawl, Girty Senior finished second in a knife fight with an Indian named Fish. The death of Simon Senior left Mary widowed with four young boys. Things were rough, and they often went to bed hungry. After a couple of very lean years, Mary married an older man named John Turner.

A Mad Dog.

Turner provided for the family, but he was meaner than a mad dog. He often got drunk or angry about something and beat the boys or Mary. The boys hated their stepfather. During that time, the French and Indian War was going on. Fearing for his safety, Turner moved the family to a location near to Fort Granville so that they could seek safety in the fort in case of an attack.

On July 30, 1756, a combined force of French and Indians overran Fort Granville and burned it to the ground. Fifteen-year-old Simon and his stepfather were taken captive by the Senecas. His mother and brothers were taken by the Shawnees and Delawares. The Senecas tortured old man Turner to death in front of Simon. However, it is unlikely that Simon shed very many tears because he hated his stepfather.

The Senecas adopted Simon, and he lived with them for the next eight years during which time he became very well liked among the Indians. He learned their languages and customs and was able to interact with Indians from several of the other tribes in the region and also learn their languages. Girty had a very friendly and outgoing personality which helped him to make a lot of close friends among the Indian tribes.

When French and Indian War ended in 1763, Chief Guyasuta negotiated the peace agreement on behalf of the Iroquois Confederacy. The treaty provided that all white captives would to be returned, so Simon was reunited with his mother and brothers at Fort Pitt in 1764. Because of his knowledge of the Indian languages and customs and his friendships among the Indians, the British Indian Department at Fort Pitt immediately offered him a job as an interpreter and negotiator and liaison with the Indians.

Simon served in that capacity for 11 years. At this point it is worth noting that some historical accounts describe Girty as a loner who had few or no friends. Actually, that is far from the truth. Simon was very well liked by the whites and the Indians. He had a lot of friends among both groups. If he had a best friend, it was Simon Kenton who was a prominent figure during the American Revolution.

By 1772, the British had decided that Fort Pitt was not needed and removed their troops leaving the fort empty. However, Girty continued to serve the British Indian Department in the Pittsburgh area until 1775, when the Pennsylvania Militia under the command of General Wood took over Fort Pitt. Wood offered Girty a lieutenant’s commission in the Pennsylvania militia if he would continue to serve as a liaison with the Indians for the militia. Girty wanted a Captain’s commission, but he agreed to take the lieutenant’s commission based on the promise of General Wood that he would be raised to the rank of Captain within two years.

However, Girty never got his promotion to captain.

In the spring of 1777, General Edward Hand took over command of Fort Henry with orders to establish a western command for the Continental Army at the fort. General Hand disliked Girty immediately and became extremely upset when he found out that Lieutenant Girty was giving anatomy lessons to the general’s 15-year-old daughter who wanted to marry Girty. General Hand did not want his grandchildren to be named Girty, so he invented a treason charge against Girty and had him arrested.

Making Sense of Girty’s Life.

This is a point in the story where a major diversion is necessary so that all of the events in Girty’s life will make sense. It will seem like a crazy non-sequitur, but you will understand it later. (By the way, most of my friends will be impressed that I even know the term “non-sequitur!”)

You will recall that a Moravian Christian missionary named David Zeisberger established settlements of Christian Indians in Ohio at Salem, Shoenbrunn, and Gnaddenhutten, where a British Missionary named John Heckenwelder later joined him as his assistant. During the summer of 1777, Zeisberger learned that the British were recruiting a force of Indians for an attack on Fort Henry.

Although the Christian Indians were committed to remaining neutral in the war, Zeisberger sent a messenger to Fort Pitt to inform General Hand of the impending attack on Fort Henry.

Hand ordered several Militia units to go to Fort Henry to reinforce the Garrison there. He also ordered Col. Andrew Swearingon at Holliday’s Fort (where Weirton is today) to take some provisions to Fort Henry by canoe. The attack on Fort Henry took place on Sept. 1, 1777, but the combined force of British and Indians failed to take the fort.

Somehow, the British learned that Zeisberger had informed General Hand about the plans for the attack. A few years later (1781), the British sent a combined force of Indians and British regulars to the three Christian towns and removed the Christian Indians. Zeisberger and Heckenwelder were taken to Fort Detroit and put on trial for treason, and all of the Christian Indians were relocated to a settlement, which became known as “Captive Town,” on the Sandusky River near Lake Erie. The move left Shoenbrunn and Gnaddenhutten abandoned.

It was well known around Fort Pitt that Simon Girty did not agree with the plans that the American side had to erase the Indian problem by eliminating them. General Hand used this general knowledge to accuse Girty of being a British spy and informing the British that Zeisberger had warned the American side about the Fort Henry attack plans. Hand conjured up a reason to have to make a trip back east for a couple of weeks. He left instructions that Girty would be arrested and charged with treason after he left and made it very clear that he wanted Girty to be found guilty and executed.

During the time that he was away, Hand expected that a quick trial and execution would take place. By making sure that he was not involved in the trial and execution, Hand was sure that he could avoid alienating his daughter. However, the plan failed because Girty had too many friends, some of whom were on the jury. Girty was acquitted of the charge.

Girty decided to get out of Pittsburgh, so he and his three brothers, along with a dozen of their friends, packed up and headed to Fort Detroit. On the way, they encountered a good-sized group of Indians who recognized Simon. A number of the Indians accompanied the party to Fort Detroit to ensure that they arrived safely. The group arrived at Fort Detroit in the late spring of 1778.

At Fort Detroit, Simon was immediately greeted by several British officers whom he knew from Fort Pitt. He was welcomed and offered his old job back with the British Indian Department. His assignment was to work with the Indians to obtain their support for the British during the war. While he was at Fort Detroit, Simon met a girl named Catherine Malott, who had been taken captive by the Delawares and turned over to the British at Fort Detroit. She was considered to be the prettiest girl in Detroit. Girty married her in 1784, and they eventually had four children.

Girty’s work with the Indians took him into Indian villages throughout the region. During one such visit, some of the Indians rode into the village with a white captive. Their prisoner had been stripped naked and painted black with ashes from the fire which was an indication that he would be tortured to death. When Girty saw the prisoner, he immediately recognized his old friend, Simon Kenton. He rushed over, wrapped his arms around Kenton, told the Indians that the man was his good friend, and asked them not to harm him.

The chief and many of the braves were also Girty’s close friends, so Kenton was untied. His belongings, including his gun and horse, were returned to him, and he was released unharmed.

A Traitor?

The Americans hated Girty. They considered him to be a turncoat and a traitor. However, his reputation as a villain was sealed by the events surrounding the death of Col. William Crawford on June 11, 1782.

Before I recall that story for you, though, we need to finish the story about the Christian Indians from Ohio! When we discontinued that story a few paragraphs ago, the Indians had been relocated to Captive Town on the Sandusky River by the British during the late fall of 1781 leaving the towns of Shoenbrunn, and Gnaddenhutten abandoned. The winter of 1781-82 was very harsh.

By the spring of 1782, the Indians at Captive Town were starving, so around 100 of them decided to go down to Gnaddenhutten to harvest some corn.

Indian raiding parties had been using the abandoned towns as campsites during their travels. While the Christian Indians were there, a raiding party came through the area. Even though they were told not to do so, a couple of teen-aged girls from the Christian Indian group traded some food for a dress that was still stained with the blood of the girl who was wearing it when she was killed by the Raiding party.

Col. David Williamson and three companies of Pennsylvania Militia went from Fort Pitt to Ohio to burn the abandoned towns so that the raiding parties could not use them. When they arrived, they were surprised to find the Christian Indians. The militia discovered the teenaged Indian girl wearing the blood-stained dress and Col. Williamson immediately concluded that the Christian Indians were the raiding party who had slaughtered the girl who owned the dress and her family. He ordered the Indians to be confined in the chapel and sentenced them all to death.

Some of the militiamen refused to participate in the execution and left for home. The next day, March 8, 1782, Williamson’s men killed 96 innocent Christian Indian men, women, and children.

In 1781, Col. William Crawford retired from the military. He was asked to come out of retirement during the summer of 1782 to lead an army into the region surrounding the Sandusky River in Ohio to deal with the hostile Indians there. However, the British and Indians got word of the campaign and Crawford’s army was badly defeated by the Indians. During the chaotic retreat, Crawford was captured along with an army surgeon named Dr. Edward Knight and nine other men. Crawford and Knight were brought into the village of Chief Pipe. The other nine men were put to death. Chief Pipe remembered Col. Crawford from his interactions with the Colonel at Fort Pitt.

At that time Crawford was Capt. David Williamson’s superior officer. Pipe informed his people that Crawford was the commanding officer of the man who was responsible for the slaughter of the 96 Christian Indians at Gnaddenhutten and ordered that Crawford be stripped naked and painted black, signifying that he was to be tortured to death in revenge for the deaths of the innocent Christian Indians. Simon Girty happened to be in the village at the time and Crawford pleaded with him to intervene.

The torture of Crawford, on June 11, 1782, is well documented, so I will not describe the gruesome details, but several times, Crawford begged Girty to shoot him to end his suffering. However, Girty sat quietly next to Chief Pipe and did nothing. The historical accounts disagree about how Dr. Knight survived to tell the story. Some accounts say that he somehow escaped from the Indians, but that is very unlikely.

Other accounts say that Girty was able to convince Chief Pipe to turn Dr. Knight over to the British who eventually released him or ransomed him which is more likely. When he returned to Fort Pitt, Knight described how Girty did nothing while Crawford was slowly tortured to death thereby sealing Girty’s reputation as “Dirty Girty” the “White Savage.”

The truth is that Chief Pipe forbade Girty from intervening by telling Girty that he would take Crawford’s place if he interfered. So, Girty had no choice but to watch the torture. However, Pipe did agree to give Knight over to the British at Fort Detroit.

After the war ended, the British Crown gave Simon Girty a land grant in Ontario for his service to the Indian Department. A couple of documents mention Girty after the war ended. When William Clark was travelling through Indiana in preparation for the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804, he met Girty at an Indian camp. Clark recorded the encounter in his journal: “26 March, 1804 – Visited the Indian camps. In one camp found three squaws and three young ones, In another, 1 girl and a boy. In a 3rd, Simon Girty and two other family. Girty has the rheumatism very bad. William Clark.”

A couple of accounts describe Girty as participating actively in the war of 1812. However those accounts are probably not true since Girty would have been 71 years old with “rheumatism very bad” and failing eyesight. Girty was almost totally blind and could hardly walk when he died at his farm in Ontario in 1818.

The inscription on the large marker on Simon Girty’s grave at his farm in Ontario reads: “A faithful servant of the British Indian Department for twenty years.” A nearby historical marker describes Girty as “Serving native nations as interpreter, scout, and military leader.”

If I have some of the details of this story wrong, I invite the real historians to correct them. Remember, my motto: Never let the facts interfere with a good story!”