Editor’s note: On July 16, the Ohio County Public Library hosted two experts at its Lunch with Books series. Dr. Matthew Mehalik, Ph.D., and Dr. Ned Ketyer, M.D., spoke to a crowd of over 100 about the environmental and health effects of cracker plants. In this piece, we’ll look primarily at Dr. Ketyer’s research. Read Part 1 here.

Natural gas has transformed the Ohio Valley. As development continues to expand, both the gas industry and the federal government intend to establish an Appalachian petrochemical hub here. Per the gas industry, building cracker plants in our region will bring economic benefits. But according to two experts who spoke at the Ohio County Public Library’s Lunch with Books on July 16, the accompanying environmental and health effects may be dire.Dr. Matthew Mehalik, Ph.D., and Dr. Ned Ketyer, M.D., F.A.A.P., have been researching and speaking about Shell’s cracker plant in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Most of their data look at that plant. They explained that the Ohio Valley can expect similar effects if the cracker plant proposed by Thailand-based company PTT is built in Dilles Bottom, Belmont County.

AIRBORNE POLLUTION

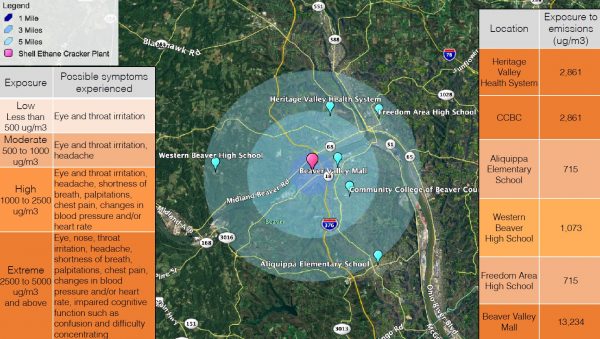

Ketyer is a pediatrician and a consultant for the Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project, which has been conducting research in the form of air modeling. The group looked at the health impacts of cracker plants using only 50 percent of the emissions allowed the Shell plant by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). They studied effects at one mile, three miles and five miles from the plant with regard to chemical emissions, nitrogen oxide, carbon monoxide and volatile organic compounds. They also looked at fine particulate matter and other hazardous air pollutants such as formaldehyde.

“The exposures are going to be significant,” Ketyer said of the findings. “If there’s low exposure, you’re just going to get some eye and throat irritation. … That ramps up the more exposure that you have. For extreme exposures, you get that upper respiratory irritation, but you also get headaches, shortness of breath, palpitations, chest pain, changes in blood pressure and impaired cognitive function.”

The Beaver Valley Mall sits due east of the Shell cracker plant. The mall is also home to a head start program and a senior center; its visitors will have extreme exposure. A nearby community college will also experience extreme exposures.

The Heritage Valley Health System is three miles away; patients visiting their doctors will be exposed, as will students in two nearby school districts.

“They’re going to have some moderate exposure,” Ketyer said. “So those students in high school will expect some throat irritation and headaches. Again, [that’s] just 50 percent of what’s permitted.”

Unlike coal and steel, emissions from cracker plants and gas wells are often invisible. The industry isn’t required by law to disclose what chemicals they’re using, but those chemicals do settle in low places.

“Pollution tends to travel along valleys and river valleys,” Ketyer said. “So the Ohio River is a conduit for the pollution that’s going to come from this cracker plant. The pollution is going to be significant.”

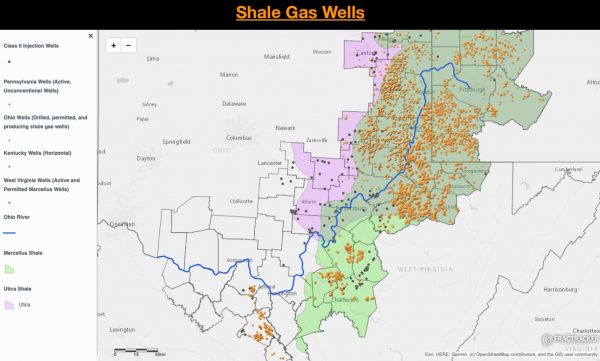

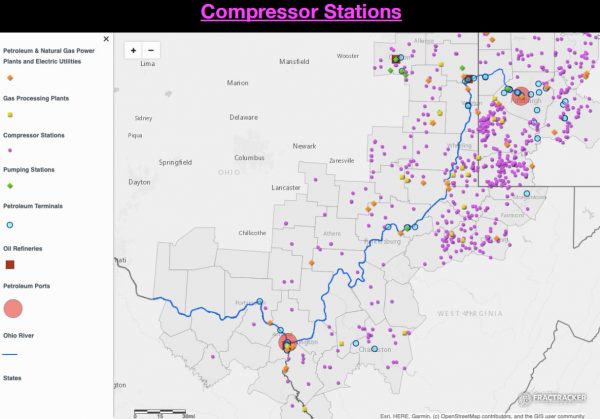

“I just want to point out that Wheeling is in the bullseye,” he added. Maps of gas wells, pipelines and compressor stations all have one thing in common: Ohio, Marshall and Belmont Counties are in the middle.

PETROCHEMICAL HEALTH HAZARDS

We can look to Louisiana for an example of an established petrochemical hub. In the Lower Mississippi River Valley between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, over 100 cracker and petrochemical plants, plastics facilities and refineries are in operation.

“There’s another name for this area,” Ketyer said. “You’ve probably heard it before. It’s ‘Cancer Alley.’”

This includes the town of Reserve, located next to the Denka/Dupont neoprene plant. CBS news has reported that Reserve has a cancer rate nearly 50 times higher than the national average. In 2017, Pittsburgh Quarterly ran a piece titled “Petrochemical Alley”; it revealed that Louisiana and southwest Pennsylvania have some frightening commonalities.

Per the article, “The south Louisiana chemical corridor and parts of southwestern Pennsylvania share some of the highest rates of cancer risk due to toxic emissions in the nation, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s most recent National Air Toxics Assessment data.”

Southwest Pennsylvania has experienced an increase in the number of people diagnosed with rare cancers. As reported in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 27 cases of Ewing sarcoma, a rare bone cancer, have been diagnosed in the last 10 years in Westmoreland, Washington, Green and Fayette counties. (On average, about 200 cases are diagnosed annually in the U.S.) Forty cases of other rare cancers in infants, children, teenagers and adults were also diagnosed. In total, 67 rare cancers appeared in children, teens and young adults. Six cases of Ewing sarcoma were diagnosed in one Washington County school district alone.

The Pennsylvania Department of Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are investigating to determine whether these cases constitute a cancer cluster. Ewing sarcoma has no known cause, and there is no proven link between the diagnoses and the gas industry. Nevertheless, Ketyer, Mehalik and some parents of the children and young people who died would like to see it investigated, as there are sources of pollution, many well sites and compressor stations in the area.

“Compressor stations are highly toxic,” Ketyer said. “Data stemming from CHP (Concerned Health Professionals of New York) in 2017 showed that every compressor station routinely releases large volumes of chemicals associated with a variety of diseases and disorders.”

Problems include breathing issues as well. A 2017 peer-reviewed study by Allegheny Health Network pediatricians found that “eight school systems exposed to the highest levels of particulate pollution from industrial sources had 1.6 times the risk of an asthma diagnosis.”

GAS INDUSTRY POLLUTION

The gas industry as a whole is a source of pollution; pipelines, processing facilities and compressor stations all add to the environmental burden. Toxic emissions occur at every stage of the process. Ketyer spoke in depth about the health hazards associated with fracking waste, explaining that millions of gallons of freshwater chemicals and sand are pushed through the well to crack the shale. From these cracks, the gas is drawn. Additionally, other things come to the surface, too.

The solid drill cuttings — rocks and mud — come up contaminated with fracking chemicals, as does the water. Both must be disposed of. Ketyer explained that fracking chemicals can cause cancer and endocrine disruptions; they may also be irritating to the skin, gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system. In addition, natural elements including lead, arsenic and radioactive materials come up. The radon gas that returns causes lung cancer; methane is also toxic.

According to Ketyer, “What goes down is a lot of water, sand and chemicals. What comes up is that and more. And this is happening around where people live. It’s happening around where kids are going to school.”

A new study by researchers at the University of Colorado found that mothers who lived near oil and gas extraction activity were 40 to 70 percent more likely to give birth to babies with congenital heart defects. Seventeen million Americans live within a mile of an active well site.

IMPACTS ON PUBLIC HEALTH

Even those who maintain good health will be faced with a societal burden.

Dr. Mehalik addressed the health care impacts on our region should it become a petrochemical hub. With three plants eventually in operation, we can expect to see a significant jump in annual health care costs. Ohio County’s yearly costs will jump from $1.3 million to $3.1 million; Belmont County’s will increase from $5.7 million to $12.9 million. Notably, over a period of 30 years, Belmont County’s health care costs will rise from $172 million to $388 million. These projections are based solely on particulate matter and do not take hazardous air pollutants into consideration.

MANY AT RISK

As with most health hazards, pregnant women, fetuses, infants and children are most at risk. Similarly, the elderly and people with pre-existing conditions such as heart and lung disease and diabetes are vulnerable. Industry workers who will be exposed daily need to be concerned, as do people who work outdoors. Ketyer added that our first responders are also in danger.

“This is personal for me,” he said. “My middle son is a volunteer firefighter in Washington County. And I kind of resent that you can be called into an emergency and not know what you’re going to be exposed to. That’s just not right for first responders.”

THE BIG PICTURE

Any one of the health or environmental hazards associated with the gas industry could be calamitous; taken together, we’re faced with an overwhelming threat. Every step, every phase, exposes the population to toxins. Moreover, the overall impact on our climate is significant. Those who don’t live near a cracker plant still face the problems associated with climate change.

“Fracking accelerates climate change,” Ketyer said. “It is so important for people to understand that fracking natural gas is not a bridge fuel … to the future. It really is a breakdown on the highway to climate catastrophe. Forty years from now, children will live in a world shaped by our choices. And so the choice is very simple in this area of the country. Planet over plastic.”

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.