Editor’s note: On July 16, the Ohio County Public Library hosted two experts at its Lunch with Books series. Dr. Matthew Mehalik, Ph.D., and Dr. Ned Ketyer, M.D., spoke to a crowd of over 100 about the environmental and health effects of cracker plants. In this piece, we’ll look at Dr. Mehalik’s research.

The Ohio Valley is preparing for completion of the Beaver County, Pennsylvania, ethane cracker plant and the possible construction of a second cracker plant in Dilles Bottom, in Belmont County, Ohio. Shell Chemical Appalachia LLC expects the Beaver County cracker plant to be operational in the early 2020s. The facility is located on the banks of the Ohio River in Potter Township, about 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. The Belmont County cracker plant is being proposed by PTT Global Chemical, a Thailand-based chemical company.The gas industry intends to make the Ohio Valley a petrochemical hub, with more cracker plants proposed in our region for the future. While the industry argues that this will benefit our area economically, many environmental scientists and health experts are concerned about the effects such development will have on the region and the people who live here.

WHAT EXACTLY IS A CRACKER PLANT?

We all know our area is home to Marcellus and Utica shales that contain natural gas reserves. Through hydraulic fracturing (fracking), gas — both wet and dry* — is extracted from the shale. An ethane cracker facility takes the ethane out of the wet gas and processes it into ethylene. This is accomplished by heating the ethane up to extreme temperatures and “cracking” the molecular bonds that hold it together. Ethylene is the root chemical for plastics; everything from resins and adhesives to PVC, plastic food wrap/containers and pharmaceuticals is born of ethylene.

*Dry gas is used to heat homes and cook food, while wet gas contains the building blocks of petrochemicals.

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

In addition to teaching at Carnegie Mellon University and Heinz College, Dr. Matthew Mehalik is the executive director of the Breathe Project, a Pittsburgh-based group of 32 organizations working together to improve airshed quality. Though much of his data focuses on southwestern Pennsylvania, he stressed that we share an airshed and a watershed with Pittsburgh. Thus, their problems tend to be our problems.

In the last 100 years, Pittsburgh’s air quality suffered from the effects of industry. Many people remember the skies turning black with smoke and polluted rivers. Thanks to environmental regulation, Pittsburgh and the Ohio Valley are cleaner than they used to be (though the Ohio River ranks as the most polluted in the nation). Nevertheless, Pittsburgh’s air quality is still poor. In fact, the American Lung Association gave Allegheny County straight Fs for air quality. (That includes both ozone and particle pollution. The latter includes but isn’t limited to sulfuric acid, ammonium nitrate, soot, metals, dust, pollen and mold spores, all of which can enter your home from the outside.) The only other place in the country to receive Fs is California.

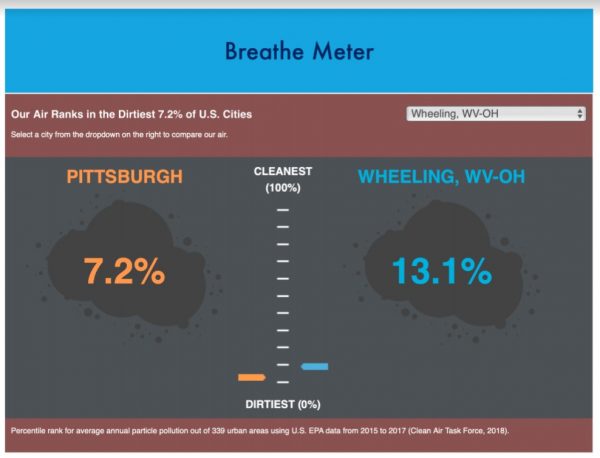

Ohio County received a C for ozone and a B for particle pollution. In 2017, a study showed that the air in the Weirton-Steubenville area was considered “not good” 181 days out of the year (half the time). Similarly, data from 2018 ranked cities with the worst air, with one being the dirtiest and 100 being the cleanest. Wheeling landed at 13.1, while Pittsburgh’s score was an abysmal 7.2.

We’re already struggling, and Mehalik said those scores will decrease if a cracker plant goes into operation in Dilles Bottom.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Wheeling is in an unfortunate position when it comes to the construction of both existing and proposed cracker plants. We are downstream from Shell’s Beaver County plant; Mehalik warns that the water used in the Pennsylvania plant will flow east to west, right past Wheeling’s intake pipes. Meanwhile, should the PTT plant come to fruition, its air emissions will flow east, over Wheeling and on toward Pittsburgh.

“You are emerging as the center bullseye of the growth of the petrochemicals,” he said to the Wheeling crowd. “The footprint of this industry is already pretty huge. And it’s getting bigger.”

In Pennsylvania, that footprint currently includes 11,682 gas wells which, in total, have incurred 13,656 violations. On average, that’s about one violation per well. (West Virginia statistics are difficult to obtain.) Mehalik cited the example of the Revolution Pipeline, which exploded in a residential neighborhood within one day of being turned on.

“There was a series of homes on the hill there,” he said, referencing a photograph of a charred landscape. “They basically were torched. Fortunately, no one was killed. But this neighborhood is gone. It’s just wiped out.”

CONCERNS ABOUT THE PROCESS

It’s important to remember that, for the gas to reach the cracker plant, a well must be drilled, fracked and the contaminated water disposed of in an injection well. The gas proceeds via pipeline to the plant. There are many aspects of the gas industry that Mehalik worries about, including injection wells. He explained the process:

“So when you frack a well, they’ll drill up to four miles underground, laterally, put a lot of water and chemicals there to crack the rock, and then the gas comes back. But also, all that water comes back contaminated. And they need to do something with that. So right now, they’re mainly hauling it into Ohio and dumping it in Ohio.” Ohio, however, is running out of disposal wells, and Pennsylvania doesn’t allow them because of its specific geology. Thus, the industry is looking to Virginia and West Virginia.

“They’re taking highly contaminated water that contains radiological components from whatever was down in that fracking layer and then dumping it in a well and just sort of trying to walk away from it,” Mehalik said. The concern is that these chemicals may leach into the groundwater supply. In addition, the U.S. Geological Survey has found that injection wells can trigger earthquakes, as we saw in Youngstown on Dec. 21, 2011, when a magnitude 4.0 shook the area.

Our region can expect continued drilling, as a cracker plant cannot function without a steady supply of wet gas. Shell’s Beaver County plant will require 1,000 new wells every three to five years to maintain steady production. PTT’s plant would be roughly the same size, doubling the number of wells in our region.

THE PROMISE OF JOBS

The industry assures locals that cracker plants offer a glut of jobs. However, according to Mehalik, this is deceptive. While the Beaver County plant employs 6,000 during its construction phase, upon completion, it will employ only 400-600 full-time workers. Many of those jobs will become automated; many of the new hires will be from out of state, particularly from states where the petrochemical industry is already established.

What’s more, the plastic produced won’t be staying local, or even national, as there’s no demand.

“[The industry] plans on increasing plastic production capacity almost 60 percent by the year 2025,” Mehalik said. “The U.S. demand is only 1.5 percent per year. So where’s that going to go? Their projection is to sell it to China.” However, because of the trade war with China, none is currently being sent over.

Plastic has been found on the most remote island in the world. It doesn’t decompose; it only breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces. It’s been found in birds’ and whales’ stomachs; when we eat fish, we’re also eating plastic. The National Academy of Science found that only 14 percent of plastic is captured and recycled, and of that, only 2 percent is actually reused. The world is drowning in plastic.

IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

The United States is the second-largest emitter of carbon dioxide, behind China. CO2 is the greenhouse gas primarily responsible for the warming of our planet’s atmosphere. Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection has granted the Beaver County plant an emissions permit to release 2.2 million tons of CO2 each year. That’s the equivalent of 430,000 vehicles, roughly half the registered vehicles in Allegheny County. The plant will be doubling the carbon footprint of southwestern Pennsylvania’s transportation each year.

This comes in addition to the particulate matter that falls back to earth.

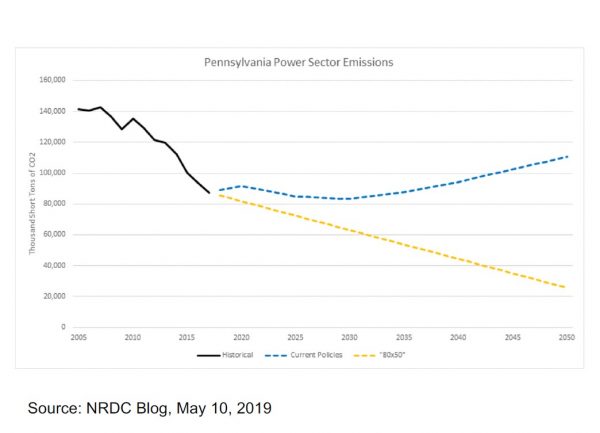

Carbon emissions in Pennsylvania have been trending downward with the conversion of coal-fired plants to renewables. Still, we’re nowhere near where we need to be to meet the climate change goals by the International Panel on Climate Change, and when the cracker plant begins operation, it will reverse that downward trend.

A STERN WARNING

Humanity has roughly 10 years to limit climate change catastrophe, and Mehalik’s research indicates the gas industry is leading us in the wrong direction.

“The climate change implications of this industry are disastrous,” he said. “Our grandkids will look back at these decisions and say, ‘What is wrong with you if you don’t do something to stop this?’, because the infrastructure we build now will be here for 50 or 60 years. Growing up in the Mon Valley in southwestern Pennsylvania, those steel plants in Homestead … were 80 or 90 years old before they stopped working. So that’s the type of investment that we’re talking about. Three generations from now, we’ll be dealing with the consequences of the decision.”

He concluded by reminding the crowd how deeply connected we are to each other and the world around us. We share the same resources. He believes this area is worth fighting for.

Find more information on Dr. Mehalik’s research at www.breatheproject.org.

In the next installment of this series, we’ll look at the health effects of cracker plants as presented at Lunch With Books by Dr. Ned Ketyer, M.D.

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.