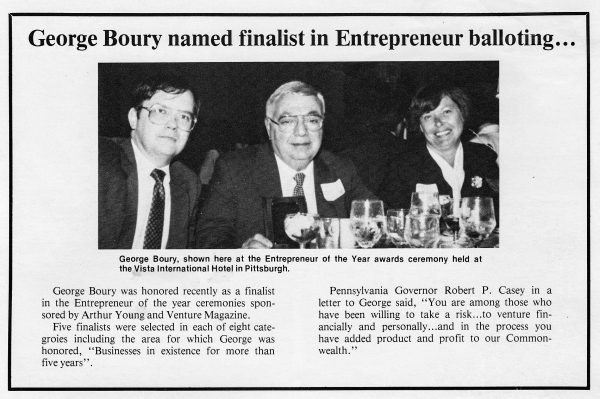

(Writer’s Note: This is the sixth in a series of stories that will concentrate on the history of one of the most storied restaurant franchises in Wheeling since the 1950s.)

What most people were jealous about was the fact they could have as many pieces of strawberry pie as they wanted. They owned it, after all.

There were three brothers, sure, who showed up in most of the promotional photographs; that was the brand – three immigrant kids who had done well in America. Michael Boury was simply the food genius, and brother Ellis was the one seldom seen unless he was purposely acting out the part of the not-so-secret “shopper” by eating at whichever Elby’s he’d targeted because of customer reviews.

And then there was George, a gambler in both his professional and personal life who took enormous chances in and out of the office that were all part of his inveterate nature. George loved sports betting, and most days he believed he’d collected enough insider information to make him unbeatable against whatever odds.

And he did win, sometimes big, but gamblers always lose, too.

The brothers all drove the latest Cadillacs while living in spectacular houses in the best neighborhoods in the city, and they had vacation homes; they wore monogramed button-downs, and all three attracted celebrity-like attention when appearing in the community they dutifully adopted.

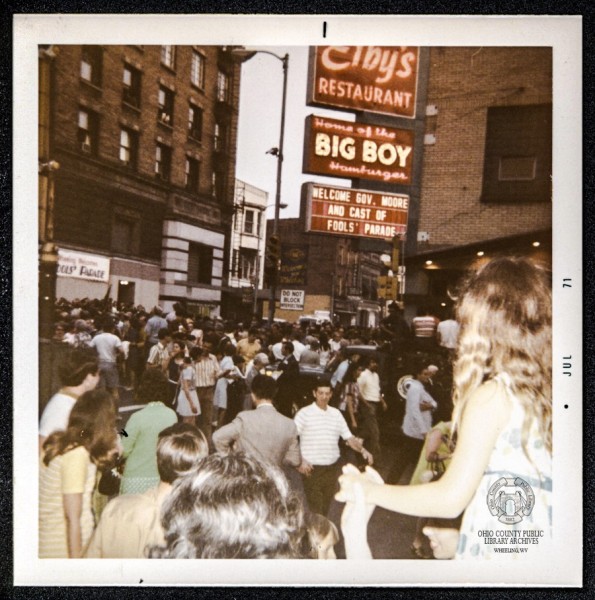

“At one time Elby’s and Boury Enterprises was a huge part of this community from a business standpoint, and any business of that size, they believed, needed to be a part of the community, too,” said Gregg Boury, the youngest son of George. “At one time it was the biggest, or close to the biggest, company in Wheeling for a while, and it was important to them to pay their community back for their support.

“I can’t tell you how many people who have come up to me through the years and have told me that they wouldn’t be in business today if my dad had not floated them a loan,” he said. “Most people don’t know that part.”

And while millennials may not remember Elby’s well, those above the age of 35 do, and many former employees admit they wish they could return to what they refer to as the “Golden Years.”

“I absolutely miss that job, and if we could go back in time I would do it all over again,” admitted former Service Supervisor Donna Holmberg. “And I wouldn’t do anything differently. I met and worked with the greatest people, and people really cared about their job. It was a different era back then.

“It’s totally different today than the way it was then. The work ethic is night-and-day; it really is,” she insisted. “These days many people don’t seem to want to work hard to earn what they earn. I just don’t get that. I was brought up the hard way, and I had to work for everything I had, but the work ethic today makes me cringe.”

Three Brothers, Three Roles

The three sons all became husbands and fathers, and many of those family members became involved in the family business in one way or another. Some were managers, franchise owners, and commissary employees, while the others pursued different careers away from the Wheeling area.

Mike and his wife, Mickie, had two children, one of whom (Bonnie) is co-owner of T.J.s Sports Garden today while their son, Robert, is an accomplished composer who has won worldwide acclaim. Mike passed away at the age of 80 in November 2000.

Ellis fathered nine children with his wife, Jacqueline, following his service in the U.S. Navy during World War II. The 1942 graduate of Wheeling High School was the last of the three to pass away when he died in May 2013.

And George, a 1936 graduate of Triadelphia High School, had four children with his first wife, Betty Jo, and they all were involved with Boury Enterprises during their professional careers. It was George who returned to Wheeling from Miami in the late 1930s upon learning both of his parents had been hospitalized. He found his father’s confectionary business in ruins with the telephone disconnected and the electrical power turned off, and it was George who united with his two brothers to revive it and transform it into a multi-million dollar corporation.

George passed away in June 2009 at the age of 91.

“George was definitely the CEO of the company, and he made that clear to everyone,” recalled Bill Bryson, the company’s former marketing director who now owns and operates UniGlobe Travel in downtown Wheeling.

“Mike did the food and he was incredibly good at it. The way he operated the commissary was simply amazing to everyone. He was always looking for the best products to make the food better and better, and he would also challenge the price increases that took place over the years.

“And Ellis took care of the atmosphere in the stores, and he was constantly looking for new locations when the expansion period was taking place,” he continued. “He also paid a lot of attention to our advertising whether it was TV, the newspaper, or one of the billboards.”

It worked, and it worked very well for many years.

“When they opened that very first store, I doubt they really expected as much growth and expansion that took place,” Holmberg said. “How would they have even imagined they would someday have 76 Elby’s restaurants?

“That’s why I believe the Boury brothers exceeded their goals. I think they did a great job; I really do,” she said. “I am still in contact with a lot of former employees, and they all tell me that they really enjoyed working at Elby’s for the Boury brothers. I believe that says a lot about how they touched everyone’s lives in the areas where they had their stores.”

The growth did leverage the brothers into the millions, but one Elby’s after another was opening in Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania at a rapid pace in the 1970s and 1980s. At its height Boury Enterprises employed more than 6,500 people, and most of them were working at one of the restaurants.

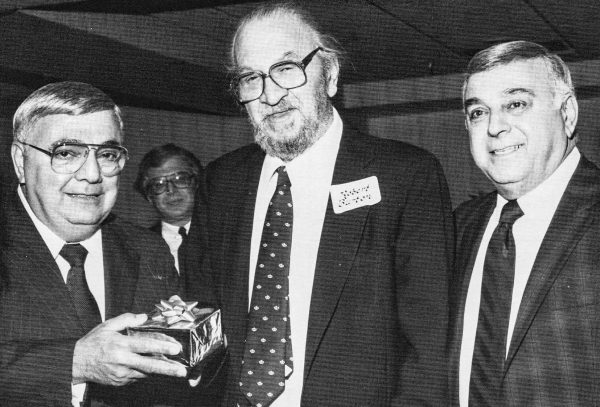

“The brothers understood that the quality of the final product was in the hands of their employees, and they decided that those people had to be recognized for living up to the expectations of Elby’s,” Boury explained. “The employees were the most imperative part of what the Elby’s experience was.

“That translated into longevity of employment for many, many of our employees. We had a lot of employees work for the company for longer than 20 years,” he said. “When we had the award banquets, it was really breathtaking to see how many we had for 10, 15, 20, even 25 years. It really became one big family for all of us who were with that company that long.”

Families, though, do fight. In the beginning, and even through the early 1980s, the three brothers worked well together, according to Bryson, while collaborating on nearly every aspect of each business under the enterprise’s broad umbrella.

“And when one of the brothers would reach a decision on something, all three of them had to sign off on it before anything happened. They would all taste the new products Mike would find, and they all would decide on the ads and the billboards and the interiors and exteriors of the restaurants,” Bryson recalled. “And in the end, the customers benefited from the best that those three brought to the table.”

But distance grew between Ellis and his two brothers, Mike and George, before the sale of Elby’s, and following the acquisition by Elias Bros. Ellis was no longer involved with the company.

“Early on I didn’t notice too much of a difference in the relationships among the three of them, but later on Ellis was not as involved. It did start to polarize that way,” Boury said. “I know my Uncle Ellis wasn’t involved with much after the stores were sold because that’s pretty much what he did for the company.

“There’s no question about it; Ellis didn’t like some of my dad’s decisions, and he didn’t approve of the way he conducted himself. And my dad didn’t appreciate Ellis very much because my dad felt he wasn’t a huge contributor to the whole thing.

“Ellis made some accusations, and the brothers really went at each other in the end. No question about it. But those things really aren’t that uncommon when things go south with a family business,” he continued. “There were the fights, and they were very personal because it was a family thing.”

“The George”

“George Boury was a giant among entrepreneurs in this part of the country. He was surly, abrasive, and cranky just as certainly as he was astute, shrewd, and clever. Along with his two brothers, he built an empire in the last half of the 20th century, and he lived long enough to see it collapse.”

Butch Maxwell composed those words near the beginning of an essay he wrote about his former boss soon after George had passed away. Maxwell began his employment following the sale of Elby’s but while George and Mike still owned several companies and were developing a new franchise idea called T.J.’s Sports Garden.

Maxwell was fired and rehired a few times when he and George would disagree on decisions, and Maxwell, who has worked in marketing and public relations for several years during his career, owns both positive and negative recollections.

“I think Butch bore the brunt of some of my dad’s frustrations after the sale of Elby’s,” said Boury. “I think he might have some inflammatory things to say about my dad, but that’s OK.”

Inflammatory? On the contrary, but he’s just being honest.

“George would drive people really crazy with some of the things he would do because had this science as far as exactly how everything had to be, and most people agreed that he was right most of the time. He had a great sense about those things,” Maxwell said. “But George, just like his brother Mike, had those neurotic qualities that would drive people crazy.

“He did a lot of the same things with me because I was his ad guy at the time. Every time I would work on a display ad, George would have to check everything, and he always changed something just for the sake of changing something,” he continued. “And then I would get it printed and give it to him, and he would get out his scissors and cut it up so he could move something an eighth of an inch. It was all to wet his post, I know, but that was the kind of control that he liked to have.”

In his six years Maxwell could recall three terminations.

“He got really mad at people, and he got really mad at me a lot after I would have to tell him something that I knew he wasn’t going to want to hear even though when he hired me, he told me that he didn’t want to hire a ‘Yes’ man,” Maxwell explained. “But what I found was that he would get really annoyed with me at those times, and he would just tell me to get out.

“When he would fire me, he would tell me to just get out, go home, and that I was done, and I’d get my check the next week. The first time I was pretty upset because I really thought I was going to have to find another job, but then he called me that afternoon and he apologized to me,” he continued. “That was one thing about George;e he would say he was sorry.”

George Boury was a flamboyant yet genius man who believed social status was important to the image of his empire. His suits were tailored, his shirts monogrammed, his shoes shiny, and his ensembles always made perfect sense.

And he loved gold.

“During the 1980s and 1990s gold was a status symbol back then, and I think he used it as such. Gold chains were all the rage back then, and so were the gold bracelets,” Boury recalled. “He also had a very impressive collection of cuff links and watches. He really had some spectacular watches.

“He cared about what other people thought of him. He really did,” he continued. “He had an affinity for the latest stuff and the features he had in that house, and the wiring it took to have all of those dimmers and light switches and the telephones was incredible. I really pity the family that bought that house after my dad lived there for so long.”

He was flashy, yes, but a part of George remained real to his roots as an immigrant kid who ran away to Miami to become a bellhop soon after graduating from high school. One of his closest confidantes was Marty Purpura, a master electrician who helped George make the amenities in his house the most modern in the city.

That was always George, the first to have the latest but blue-collar to the bone.

“I can remember when my dad got the first remote car starter in Wheeling. He had to buy it out of town, but Robinson’s put it in for him,” Boury recalled. “I used to take my friends to his house, and I would give one of them the remote so the others didn’t find it on me. I would tell one of them to tell the car verbally to start, and he would say, ‘Car start,’ and my other friend would hit the start button on the remote, and it would turn over.

“They were amazed because it was really mind blowing. But then I would tell my friend to tell the car to shut down,” he continued. “That was funny as hell to me back then, but now those remote starters are commonplace.”

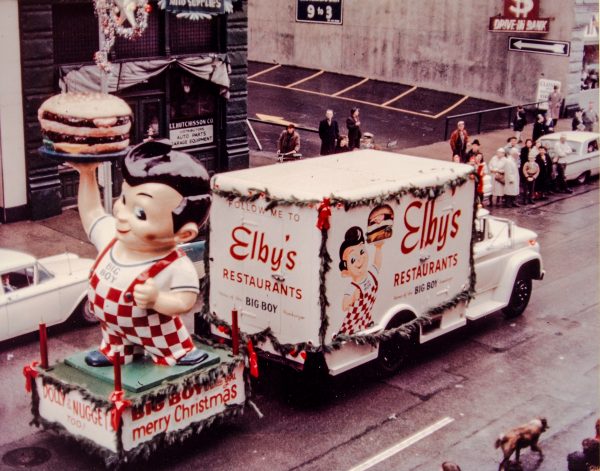

When the brothers opened their first Elby’s in 1956, the business plan was all about being the best, and that blueprint remained in place until the bitter end. At the time “Elby’s” was removed from the “Big Boy” signage, food quality took an immediate dip and constant complaints were received.

Just ask Bryson, who decided to accept a marketing position with Elias Bros. instead of staying on with what was left of Boury Enterprises.

“But in the end it was a ‘B’ company buying an ‘A’ company. That’s why they didn’t last much longer,” Bryson said. “And I learned so much from George, and I can tell you he considered himself an excellent businessman, and he was. He truly wanted everything to be the best it possibly could be, and he set the bar very, very high. There was a standard you had to meet, and everyone in that company knew where that bar was.

“Everything had to be as perfect as it could be because, honestly, he wanted to be able to brag about everything the brothers had – the restaurants and all of the other businesses,” he continued. “George pushed himself to meet his own standards and that’s why he was very, very successful for a long time.”

George Boury eventually sold his remaining assets and retreated away from the spotlight he had sought and chased for decades before. His gravesite, near his parents and other members of the Boury family at Mount Calvary in Wheeling, has no stone but does have a modest marker.

And it’s not gold.

“The sale and the financial struggles of Elby’s were really hard on him, and there was a huge change in him,” Boury explained. “And I believe he took some of the blame, but inwardly. I don’t think he was willing to do that outwardly.

Maxwell actually began his “Fallen Giant” piece with a quote from George Boury himself.

“I don’t know what all the fuss is about speaking well of the dead. He was an S.O.B. when he was alive. Now he’s a dead S.O.B.”

“That doesn’t sum him up completely, of course, but he was a son-of-a-bitch, and that was part of how he managed to get ahead in life. And he was a son-of-a-bitch to a lot of people he was closest with, like his family,” Maxwell said. “But I thought it was sad when he died because, as far as I knew after trying to find out, there was no memorial service or a wake, so there was no way of eulogizing him, so that’s what prompted me to want to write something about him.

“He was complicated. There were some wonderful things about him, and there were some really awful things about him. But he was a guy who made incredible waves in this community. My life is richer for having that experience even though, at times, it was painful,” he said with a laugh. “He was significant to me and I wrote what I wrote because I felt I wanted to memorialize him in some way, and I thought it might resonate with some people out there. That man reached and bettered a lot of lives.”

The Legends and Reality

The first time the news coverage turned negative involving the Boury brothers was very soon after the potential sale of the Elby’s franchise leaked outside the company. It was the late 1980s, and the employees admitted something was obviously wrong, and the local press wanted to get the scoop.

“The local media did start asking a lot of questions, but George really didn’t want to talk to anyone. He was very upset,” Bryson said. “But one time the people from WTRF called, so I went into George’s office, and I told him that he should probably address it. That’s when he told me that he would only speak with Mark Davis and that’s because he and Mark were friends, and he trusted Mark.

“But behind the scenes it got ugly. People started leaving. People in one of the companies were blaming the people in the other companies. The people at Boury Inc. were blaming the people at the Elby’s and the people at Elby’s were blaming people at the hotel,” he said. “It got real ugly.

“You could tell that there were money issues, family issues; there were fallouts that took place,” Bryson remembered. “I think it was when there were issues involving (vice president of operations) Tom Johnson that I really knew something was up for sure because Tom had been their main guy for so long, and then suddenly he had fallen out of their favor. And that’s about when it just unraveled in front of our eyes, and when it hit everyone that all of a sudden we weren’t No. 1. We weren’t the best.”

While he was still employed by the Boury brothers, he and others heard a plethora of rumors about the owners, but most centered on George and the man’s passion for risk.

“We all heard the rumors about the gambling, about the drugs,” Bryson said. “But it never reached the point where, in my position as marketing manager, that I had to defend anything.

“When I heard them, I ignored them because I couldn’t do anything about them. I just did my job, and we all worked hard to keep everything going as well as possible,” he added. “I didn’t know the specifics, and I didn’t want to know them. But when the time came when I had to choose if I wanted to stay with the other companies or start working with Elias, I chose Elias because the restaurants were what I was most interested in. I wanted to try to keep them going, but that didn’t end up working out either.”

Some have even asked George’s son, Gregg, about the tales they’ve heard whispered wherever about his father.

“I’m not confronted with the rumors very often because I think people tend to avoid bringing those issues up to me,” Boury said. “If they do, I set them straight. I tell them what I know, and I don’t make anything up. The past is the past, so I just tell them my understanding of the situation. My father was a tough man, but he was just as tough on himself as he was with everyone else.

“And my dad loved betting, and that was no secret. He loved gambling, and he was Lebanese, and he was the patriarch of the family so you really couldn’t tell him much about anything. He considered himself the ruler, and it was hard for a sibling to get respect from him,” he continued. “Whatever role gambling and drugs played in his life was a very minuscule part of it, and if it led to those rumors, it’s totally ridiculous, and they are strictly rumors. In his rise to being a business leader in this area there were people who got hurt in the process and those kinds of relationship breeds those kinds of rumors especially if there’s even the slightest truth to them.”

Tom Burgoyne, a special agent in Wheeling for the Federal Bureau of Investigation from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, has heard the rumors, too, but …

“I know there have been stories that George got arrested in Florida for drugs, but I’ve never been able to find any truth to it at all,” said Burgoyne. “And I know he was never arrested for drugs here in Wheeling. Never. I can’t tell you if he did drugs or not, but I can tell you he was never arrested for anything like that.

“Now, as far as gambling, I know he was going to head-to-head with Paul Hankish, and that they were pretty much using the same handicapper, and I’m sure that caused issues,” the former FBI agent recalled. “George was a compulsive gambler, and he had guys who got tips from all over the place. If the quarterback on a certain team stayed out late, he somehow knew about those things. He won a lot, but in the end, he lost. Didn’t he?”

George died in the house he built on Hawthorne Court, and soon after his burial the dwelling was sold at auction by the state of West Virginia for $200,000. Once royalty, George Boury passed away a defeated man.

“I don’t have a lot of insight into how he got into so many problems with his taxes. For me to look at it with an independent eye it’s difficult because when I heard things it was from him telling it,” Boury said. “And I knew there was another side of the story, but I never got to hear the other side of the story, so I’ve just listened and then gone about my business.

“My dad hid from the public eye during his last years because he was demoralized and depressed with everything that had transpired, so he didn’t want a lot of fanfare when he passed,” Boury remembered. “He wanted the later years to be forgotten. He did. But he didn’t want it all to be forgotten.”

And for those who were employees and consistent customers, Elby’s will forever be that place – home of the Big Boy and Brawny Lad and Slim Jim, yes, but also the empire the Bourys built.

(Cover photo archived by James Thornton)