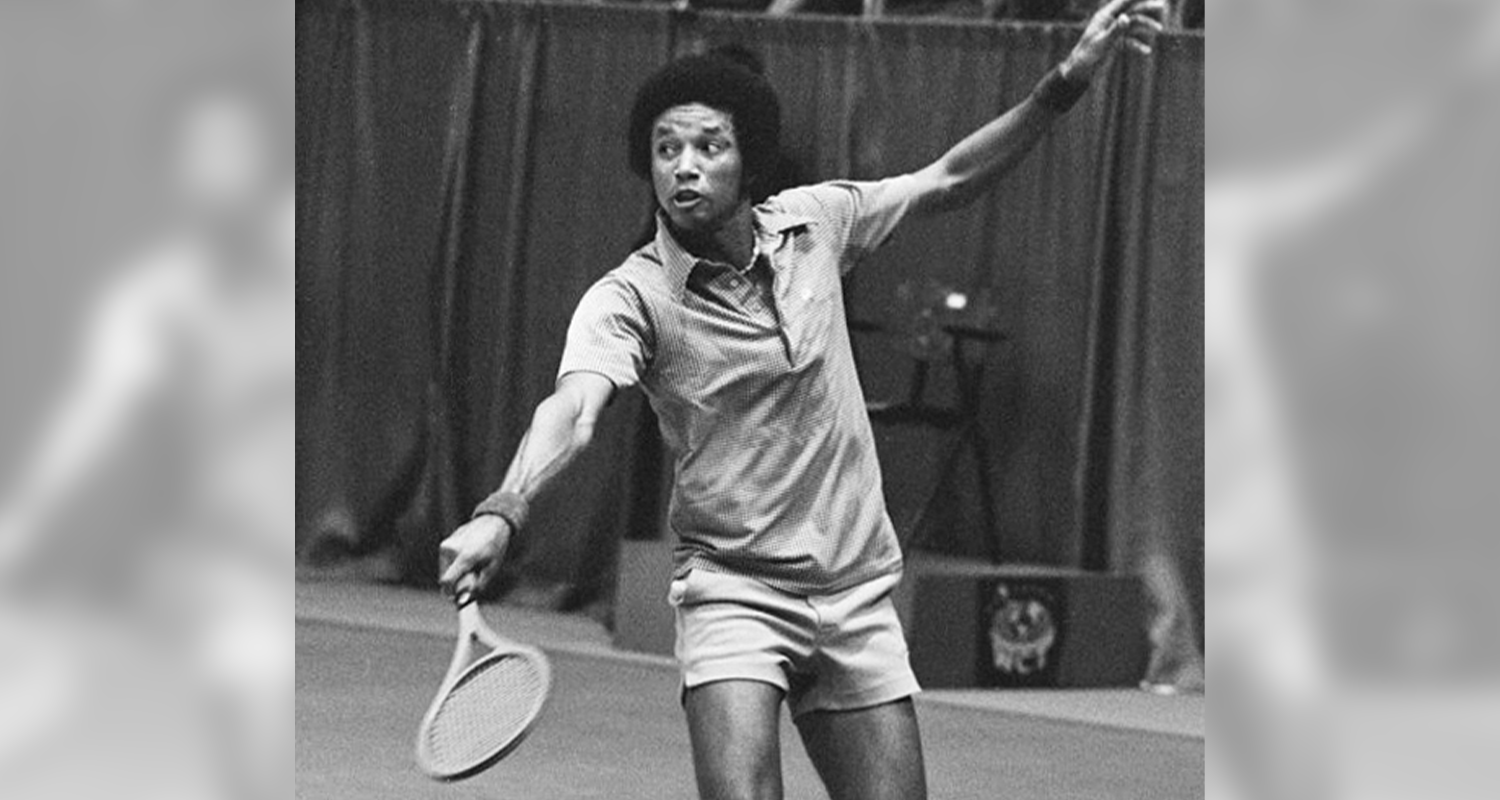

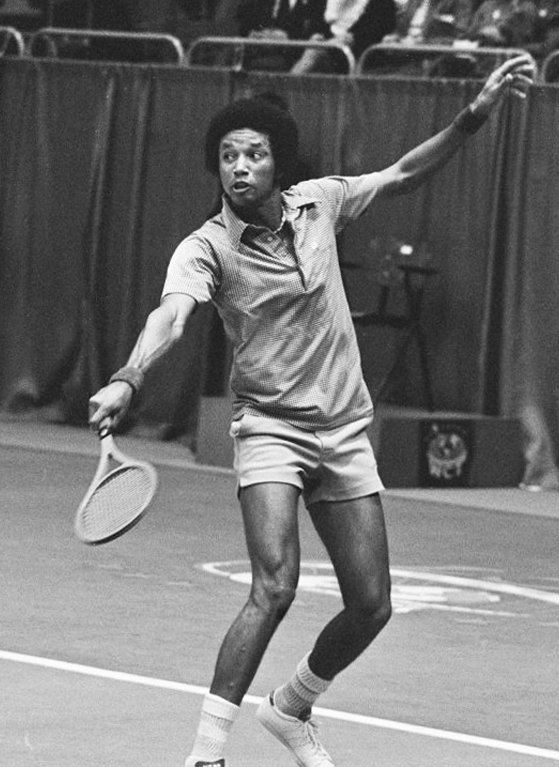

In July 1960, Wheeling had a 16-year-old visitor to the tennis courts of Oglebay. Few knew that this young African American boy would become one of the greatest American tennis players of all time. His name was Arthur Ashe.

Who was Arthur Ashe?

Arthur Ashe (1943-1993) was a professional tennis player and civil rights activist who is remembered for breaking down race barriers, on and off the court. Ashe grew up in Richmond, Virginia learning to play tennis on segregated courts; he was forbidden from practicing on white city courts and competing in city tournaments.

Despite being shut out of the white tennis circles in Richmond, Ashe’s skills and talent were noticed and he began training during the summers as a teenager with Walter “Whirlwind” Johnson in Lynchburg, VA. Dr. Johnson had created the first formal Junior Development program for the American Tennis Association (ATA), which is the oldest African American sports organization in the US, training other tennis greats like Althea Gibson—the first African American to ever win a Grand Slam title.1

Ashe eventually went on to play tennis at UCLA, graduating with a business degree. In 1963, in the middle of his time at UCLA, Ashe became the first Black player to become part of the US Davis Cup team and was eventually named captain.2 While serving in the US Army for two years, in 1968, Ashe won the US Open; he was the first Black man to win the title.3 Later that year, he also became the first Black man to be ranked No. 1 by the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA).4 Later in his career, Ashe won two other Grand Slam titles at the Australian Open and Wimbledon. He ended his professional career in 1980 with 818 wins, 260 losses, and 51 titles.5

Throughout his career, Ashe endured racial slurs and taunts at matches, was denied entry into tournaments at segregated country clubs, tennis associations refused to rank him, and even local newspapers elected to feature only white competitors.6 Even as the No. 1 ranked US men’s player at the time, Ashe was denied a visa by the strictly segregated Apartheid South Africa to compete in the South African Open in 1969.7

In addition to his impressive tennis career as a player, Ashe is also greatly lauded for his civil rights activism and work in improving lives in his community. He founded and supported numerous programs for youth and minorities, often aimed at connecting sports, education, and opportunities. After his retirement from tennis, Ashe worked and protested to raise awareness against the South African government’s Apartheid policies.8 According to the American Tennis Association, “Ashe’s success as a Davis Cup player and his US Open and Wimbledon titles are legendary. But, his recognition at tennis became the tool that he would use to challenge society to end the racial injustice that plagued the planet.”9

Arthur Ashe at Oglebay

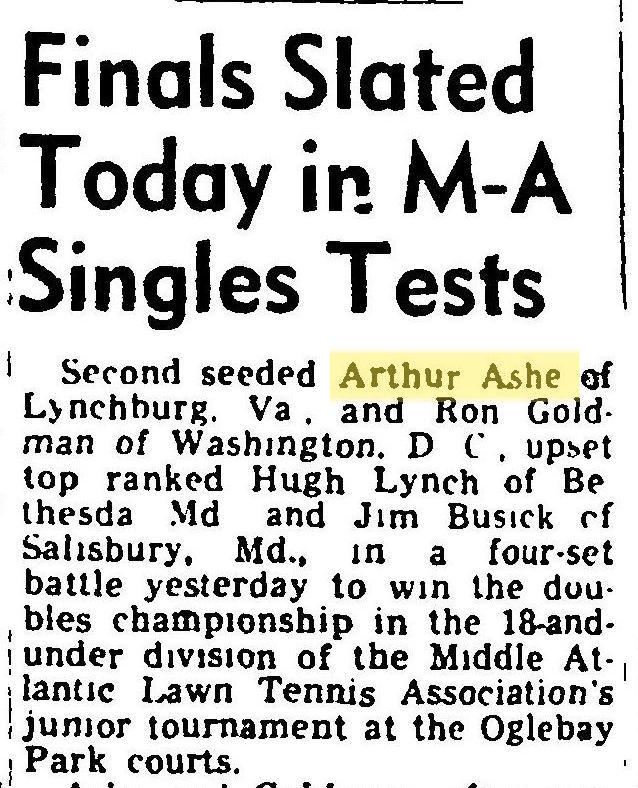

Years before his fame, the day before his 17th birthday, Arthur Ashe took to the court at Oglebay at 10am on July 9th, 1960 to compete in the 18-and-under singles finals. His competitor, Hugh Lynch of Bethesda, Maryland was seeded first. Ashe had beat Lynch the day before during the doubles championship with his partner Ron Goldman.10

A younger competitor at the tournament, Tom Chewning, was also from Richmond, but had never met Ashe until they competed in Wheeling. In fact, Chewning initially thought that the tournament director had made a mistake, but when he met Ashe he “immediately saw that being an African American, the reason that I didn’t know him was because I hadn’t been permitted to know him. We hadn’t been permitted to be playing together.”11 Ashe had been denied entry into the same tournament in years before because it was held at segregated country clubs in Richmond and Washington, DC, but was finally allowed to enter in Wheeling.

Donald Dell and his family, a tennis player who was several years older than Ashe and would eventually become his manager, would often drive Ashe home from tennis tournaments (Dell’s younger brother, Richard, often competed in the same tournaments). Dell remembers that on the trip home from Oglebay in Wheeling, they would “drive all night. We all knew that if we stopped, Arthur and I couldn’t stay in the same motel.”12 During the era of racial segregation in the 20th century, traveling on the road often posed dangers for African Americans who were unfamiliar with the segregation laws or practices of certain locales. At the time, travel guides like The Green Book were popular with Black travelers to find safe hospitality and services when far from home—including in Wheeling. Many lodging options along the southern route between Wheeling and Richmond, VA were segregated and not an option for Ashe and the white Dell family.

Throughout the tournament, The Wheeling Intelligencer dedicated a small column of the Sports Section to the results of the semi-finals and doubles finals. However, the publication after the last—and arguably the most exciting—day when the singles final would be announced…there was no mention of Ashe’s victory. He was the first Black player to win that tournament.

Ashe’s Legacy Today

Today, there are numerous dedications, memorials, and monuments to Ashe’s service, such as Arthur Ashe Boulevard in Richmond and the Arthur Ashe Stadium in NY—the main stadium used at the US Open. The United States Tennis Association did not formally forbid discrimination in its sanctioned tournaments until 1993, the same year Arthur Ashe died of pneumonia due to AIDS complications—over three decades after he competed in Wheeling.13

For a famous tennis player, an amateur tournament played in Wheeling when he was 16 may feel like a blip on a longer competitive career—there were certainly more crucial matches, more challenging opponents, and more impressive locations. However, Ashe’s appearance at Oglebay is important because it pushes us to remember the segregated state of tennis and sports that, unfortunately, wasn’t that long ago and left deep scars.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “History,” American Tennis Association, accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.yourata.org/history.

2 Sundiata Djata, Blacks at the Net: Achievement in the History of Tennis, Volume One, (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 53.

3 “The Arthur Ashe Legacy: Life Story,” University of California at Los Angeles, accessed January 29, 2021, https://arthurashe.ucla.edu/life-story/.

4 Rhiannon Walker, “Arthur Ashe becomes first African-American male tennis player ranked No. 1 in the U.S.,” The Undefeated, December 14, 2016, accessed January 29, 2021, https://theundefeated.com/features/arthur-ashe-becomes-first-african-american-tennis-player-ranked-no-1-in-the-u-s/

5 “The Arthur Ashe Legacy: Life Story,” University of California at Los Angeles, accessed January 29, 2021, https://arthurashe.ucla.edu/life-story/.

6 Matt Blitz, “As The Citi Open Turns 50, We Have Arthur Ashe To Thank For The Tournament,” dcist, July 27, 2018, accessed January 18, 2021, https://dcist.com/story/18/07/27/citi-open-arthur-ashe-history-50th-anniversary/

7 “The Arthur Ashe Legacy: Life Story,” University of California at Los Angeles, accessed January 29, 2021, https://arthurashe.ucla.edu/life-story/.

8 “The Arthur Ashe Legacy: Life Story,” University of California at Los Angeles, accessed January 29, 2021, https://arthurashe.ucla.edu/life-story/.

9 “History,” American Tennis Association, accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.yourata.org/history

10 “Finals Slated Today in M-A Singles Tests,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 9, 1960, p. 11.

11 Kristin Norton, “I Am A Citizen of the World: Constructing the Public Memory of Arthur Ashe,” Master’s Thesis, The Florida State University, 2010, p. 52, accessed January 18, 2021, https://fsu.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fsu:180802/datastream/PDF/view.

12 Matt Blitz, “As The Citi Open Turns 50, We Have Arthur Ashe To Thank For The Tournament,”

13 Warren Kimball, “USTA Key Dates,” United States Tennis Association, accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.usta.com/en/home/about-usta/usta-history/national/usta-history.html.