In the early 1900s, the United States was in the midst of the second industrial revolution. People flocked to cities like Wheeling to find employment in the many mines, mills, and factories. This work held the promise of opportunity, but it brought much uncertainty as well. Long hours, inadequate pay, unsafe work conditions, and cramped living quarters often awaited people coming to cities to work, and in many cases, it was what must be done in order to survive.

Despite Wheeling having many amenities that made it a modern city, such as paved roads, recreation facilities and good schools, the laboring classes of Wheeling were unable to enjoy these features to the same degree that their middle and upper-class neighbors could. Working-class children began entering the workforce at young ages to help support their families, and as a result, cut their time in school short. Shifts were long, both for children and adult workers, the workweek averaged from 60 to 72 hours. As one can imagine, this left little time for leisure.1

READ MORE: Uncovered in Photographs: The Children Who Worked Wheeling’s Factories

Laborers were acutely aware of the disparity between workers and the wealthier classes. They watched “robber barons” like Andrew Carnegie profit from advancements in industrial technology and market manipulation.2 The benefits of new labor-saving equipment, processes, and improved transportation meant increased production; more things made faster. However, workers were not benefitting from these advancements, financially or otherwise.

Additionally, labor practices that are regarded as standard today were not yet protected by law. The 8-hour shift, prohibition of child labor, and general workplace safety measures were among some of the ideas being hotly discussed. Looking for a way to consolidate its power, the Ohio Valley Trades and Labor Assembly (OVTLA), the country’s first central labor organization– was first organized in 1882.3,4 As the OVTLA gained momentum, they looked for ways to reach a wider audience with their ideas.

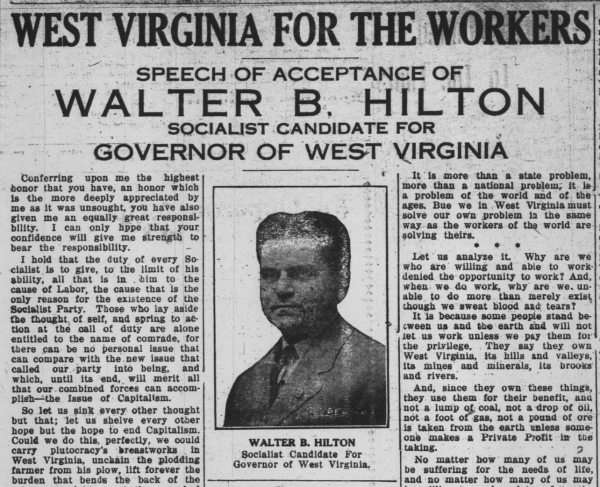

Enter: The Wheeling Majority, “the only Wheeling paper that can afford to tell the Truth– for those who plod with a plow, pick, or pen.” 5 The Wheeling Majority was a paper written by workers for workers and was meant to be a place to speak plainly about any issue concerning the readership. Founded by Walter B. Hilton, the Majority shared the offices of the OVTLA in the 1500 block of Market Street.6 Workers’ concerns ran on the front page and were not shy about naming employers engaging in unfair labor practices. The Majority also printed columns in support of women’s suffrage, equal pay, poetry, syndicated labor news, and advertisements for local union-friendly businesses.

Eugene, Walter, and the Big “S”

Then, as it does now, the term “socialism” often elicits strong emotions in people. The term, like many other political buzzwords, is often applied generally and inaccurately. At its core, Socialism is concerned with public ownership and governing of property and natural resources. Because individuals do not live or work in isolation, but rather are in cooperation, the goods they produce should be held in cooperation as well, to the benefit of all members of society. 7 Given what we know about the lives of laboring Wheelingites during the early 20th century, it’s easy to see how they were drawn to these ideals to create better– and fairer– living conditions. Can you blame them?

If it’s still unclear as to why workers would look for alternatives to the current socio-political binary of Democrats and Republicans, consider the Reuthers. In Victor Reuther’s memoir, The Brothers Reuther, he remarked how his father, Valentine, and other OVTLA members felt it was obvious that working people could not look for any help from the political parties of their employers. Instead, they felt it best to put their support behind a third option, the Socialist party.8 When the time came, Reuther and other OVTLA members put their support behind Eugene V. Debs’ multiple runs for president.9

READ MORE: Celebrating Wheeling’s Labor Heritage

Deb’s run for president was in earnest, but was also an exercise of consciousness-raising, and contributed to a political atmosphere where other socialist candidates felt comfortable throwing their hats in the political ring. Even Walter B. Hilton tried his hand at a political campaign, running for Governor of West Virginia in 1912. This was an especially interesting election year, with Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party as well as the Prohibition Party fielding a slate of candidates. While Hilton did not win, he earned around 11% of the vote in Ohio County, higher than his state average of 5%.10 Never defeated, in the week following the election Hilton wrote that political involvement is just one way to achieve better conditions, with union support being the other.

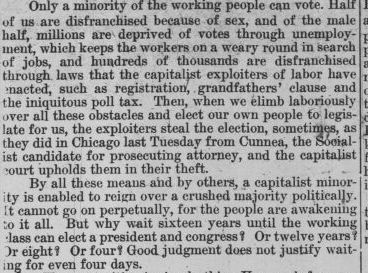

“Only a minority of the working people can vote. Half of us are disenfranchised because of sex, and of the male half, millions are deprived of votes through enmployent, which keeps the works on a weary round of search for jobs, and hundreds of thousand are disenfranchised through laws that the capitalist exploiters of labor have enacted, such as registration, grandfather’s clause, and the iniquitous poll tax.”

This was part of Hilton’s sober reminder that not everyone could vote. The 19th amendment guaranteeing women’s right to vote would not pass for another 8 years, and while the 15th amendment stated that voters would not be discriminated against on the basis of race, many states, as Hilton alluded, prevented African American men from voting through poll taxes, literacy tests, intimidation and violence. The passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ensured that all eligible citizens had the opportunity to vote.11

The Majority’s Last Run

By 1920, the Wheeling Majority folded. Walter Hilton was able to enter a second act in the finance world. One of his achievements was being involved in organizing the Wheeling Savings & Loan Association.12 Despite being involved in the “radical” paper trade, it didn’t seem to negatively affect his later career. His biography published by the West Virginia Biographical Association simply states that he was a “newspaperman, editor, and publisher until 1920.” 13

Not much is known about the last days of the Majority, apparently ceasing operations in 1920 after “landing on the shores of financial ruin.” 14 During its run, the Majority provided an invaluable outlet for the workers of Wheeling to hash out issues that concerned them. As the only labor paper of its time in the Ohio Valley, it was an important place for the growing labor movement to discuss voting rights, equal pay, and workplace protections– issues that are far from settled today.

References

1 David Javersak, The Ohio Valley Trades and Labor Assembly, the Formative years. 1882-1915 [unpublished PhD dissertation]. West Virginia University, History. 1977

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 “Ohio Valley Trades and Labor Assembly,” The West Virginia Encyclopedia. October 22, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1744

5 The Wheeling Majority. January 14, 1909. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86092530/1909-01-14/ed-1/seq-1/

6 Callin’s City Directory, Wheeling West Virginia, 1909. Pg. 721

7 Ball, Terence and Dagger, Richard. “socialism”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 11 Apr. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/socialism. Accessed 3 May 2022.

8 Victor G. Reuther. The Brothers Reuther and the Story of the Uaw. United Automobile Workers a Memoir. , 1976. Print.

9 “Eugene Debs: Topics in Chronicling America.” Library of Congress. Accessed May 3, 2022.https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-eugene-debs

10 1912 Gubernatorial General Election Results– West Virginia https://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?fips=54&year=1912&f=0&off=5

11 Milestone Documents: 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Voting Rights (1870). National Archives. Accessed May 4, 2022 https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/15th-amendment#:~:text=Passed%20by%20Congress%20February%2026,men%20the%20right%20to%20vote.

12 “Walter Burton Hilton.” WV GenWeb Project. Transcription by Linda Fluharty of entry from West Virginians, published by the West Virginia Biographical Association, 1928.https://www.wvgenweb.org/ohio/hilton.htm

13 Ibid.

14 Otto Hupp, Pioneer Newspapers: Historical Sketch on Founding of the Press in Wheeling, 1940. Quoted in Javersak, The Ohio Valley Trades and Labor Assembly, the Formative Years. 1882 -1915 [unpublished PhD dissertation]. West Virginia University, History. 1977

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.