Spooky season is upon us. Pumpkins are just waiting to be carved, horror movies are playing on Netflix, and candy corn is cool again. For some, this season is more than fall fun and games. The autumnal season is very meaningful for practitioners of the Pagan faith – from which many of our Halloween traditions have evolved.

The fall hosts Mabon and Samhain. Mabon, the autumnal equinox, is the celebration of the second harvest, with tributes made to the sun and the earth. Samhain marks the beginning of the winter season and the midpoint between the fall equinox and winter solstice. Preparations are made for the winter months, fires are lit to help guide spirits, and offerings are made to gods, goddesses, and ancestors. It is believed that the veil between worlds is at its thinnest on Samhain. That idea is just one of the traditions borrowed to create Halloween as we know it.1,2

Another tradition is the carving of turnips to create Jack-o-Lanterns, though later Irish tradition saw this changed to pumpkins. There was also a “Dumb Supper” where ancestors were invited to join a celebratory meal, where adults updated the dead on the year’s events and children played games with them. Furthermore, trick-or-treating can be traced back to an Irish practice of Murmuring, where costumes were dawned, and people traveled door-to-door singing songs to the dead in exchange for cakes.3

If all of this has you wanting to get a little witchy – you are in luck! Modern-day witches in Wheeling have a bounty of places to aid in their practice.

Wheeling’s Modern Witches

From Dyagon Alley, a longstanding shop operating on 24 Bridge Street since 2005, to the newer Card and Soul Tarot on Main Street, to the healing services you can find at Under the Elder Tree in Centre Market. There’s a place for whatever facet of witchcraft you want to explore.

READ MORE: Under The Elder Tree, Wheeling’s Modern-Day Apothecary

Dragon Alley’s owners, Brian and Jacque Daugherty, spoke about their store and their practice. The inside of their shop is packed with everything one could need to discover their own path to practice Witchcraft. “We have over 100 bulk herbs, hand-dipped incense, essential oils, candles, crystals, and books on Paganism.” Said Brian, who practices Norse and Ancestral-focused Witchcraft.

Jacque, who practices Shamanism and Earth Magic, made it clear how she wants their store to be “a sanctuary for anybody who walks through it”.

As Brain and Jacque practice different branches of Witchcraft, they are well-suited to help people find tools for their individual beliefs. They are also sure to dedicate time and research to helping people, even when they aren’t experts in the thing themselves. “There are things that we don’t practice, but if somebody wants to practice, we’ll help them anyway we can,” said Jacque. She wants to encourage people to find what best suits them. “If you believe strongly enough in something, it’s going to help you.”

She encourages people to think about the question “What is the difference between magic and miracles?” The answer is simple, she says: “Nothing.” Jacque believes that “everybody has a little witch in them.” To emphasize just how commonplace Witchcraft can be, she says that even old wives’ tales can be considered a form of Witchcraft.

Appalachian Folk Magic

Geographically speaking, it makes sense why Wheeling is a little witchy. The history of magic in West Virginia goes back decades. Folk magic, a loose combination of practices, has a long-standing hold in Appalachia. Folk practices in this region certainly take roots from the Celtic Pagans, but also incorporate herbal remedies learned from the Indigenous Peoples.

One form of folk magic that seems to particularly thrive in the mountains is the power of “water witches” who use dowsing rods to locate underground water sources. These powers were extremely helpful to those moving into new lands throughout Appalachia.4

Appalachian folk magic shows up more than one may think. Ever heard someone talk about leaves turning upward to predict rain? That’s rooted in folk magic! The sign that a red sky at dawn heralds bad weather while a red sky at dusk calls for good weather, that’s folk magic too. (As my Great-Grandfather would say, “Red sky at night, sailor’s delight, red sky in the morning sailor’s warning”.)

Folk magic can even be found in many of our self-care and hygiene practices. For example, chamomile tea for sleep can be considered folk magic, and sipping a combination of moonshine and honey is often seen as cure-all. There is also the more elaborate act of cutting a potato in half, rubbing against the ill-affected area, putting it back together with a nail, and burying it as far away from home as you can.

It isn’t all healing and prediction of weather, folk magic also has a keen sense of interpretation of omens. Leaving your shoes on the bed, while unsanitary, also predicts misfortune (or death, if you ask my mother). Spilling milk means an evil influence, or curse, has settled over the home, so maybe it actually is worth crying over. 5,6

Jacque Daugherty gave a perfect example of how folk remedies, or magic as we call it, have been the basis for many common items we use today. “Appalachia has really been strong in herbal medicines. Without herbal medicines, many regular medicines would have never been constructed. White willow bark is what they made Aspirin out of. They would peel the bark, boil it down, and take the water off of it.”

Wheeling’s Witchy History

While it’s easy to assume that witchcraft in Wheeling has largely flown under the radar, local news articles dating back more than a century suggest otherwise. Though it was far from a witch trial, there are two articles documented in the Wheeling Intelligencer from 1918 that reported on a grand larceny case centered around Mrs. Mary Loveall’s practice of witchcraft. Loveall offered a cure for a woman from East Wheeling’s ill child and took $640 (an insane $12,956 in today’s money!) for that task.7 When the child passed, she was brought to trial. Mrs. Loveall stated that she “believed in witchery and had practiced it for some time on this and the Ohio side.” On the stand, the child’s mother accused her of witchcraft. She was sentenced to four years in the Moundsville prison. She had nothing to say to this sentence.8

Another Intelligencer article from 1922 speaks to the presence of witchcraft practitioners in the area, though in a not-so-favorable light. It speaks of the “element of danger” to witchcraft. It claims that “We have, here in Wheeling, a few persons who profess to be witch doctors who take advantage of […] believers in witches.”9

Seven years later, in 1929, it seems some distaste has faded. In a section of the Wheeling Sunday Register called Tessie’s Column, the author claims: “I really personally know people here in Wheeling who secretly believe in witchcraft. A woman of my acquaintance was carrying her baby in her arms in the lower Wheeling market some months ago and covered its face when an old woman came near, remaking. ‘That woman has the evil eye and I don’t want her to look at my child.’ I know of a man in the Wheeling district who was visited by hundreds of people who claimed to be the victim of spells put upon them by enemies and who sought charms to avert their ill luck. […] Personally, I do not believe in it.”10

Per The Intelligencer, in 1932, one Dr. Theodore Diller of Pittsburgh even gave a lecture at the Ohio Valley General Hospital on ‘The Human Credulity as Illustrated by Considerations of Witchcraft’. Dr. Diller continued to chronicle the history of witchcraft, emphasizing the prevailing presence of witches.11

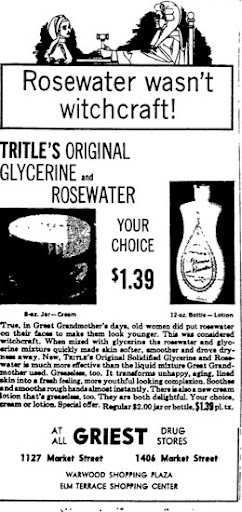

Jumping to 1965, we see witchcraft being riffed on, with a joke made about the stigma it’s received over the centuries in order to sell rosewater.

In 1972, we see a full defense for practitioners of Witchcraft. One Michael Kellar writes to the editor of The Intelligencer in defense of Witchcraft following a piece conflating witchcraft with Satanism. Keller says “Witchcraft is, as it always has been, a beautiful and sincere, though often maligned, religion. The god and goddess worshiped by its followers are very close to nature and have absolutely no connection with the Christian devil.” He laments how people “fear what they could not understand.” He ends his letter with, what is perhaps, the ultimate sentiment of witchcraft over time and in this region. “Today, these false associations are carried on out of fragmented history and ignorance. My friends wish only to be able to worship openly without being hated or feared, and this can only come about when ignorance has been eliminated.”12

While celebrating the fall season, carving pumpkins (or turnips), it’s important to remember where some of these traditions and beliefs come from. So, whether this kicks off a full-blown interest for you, or just scratched the curious itch, I hope you enjoyed learning just a little about the witches, past and present, of Wheeling.

References

1 “Samhain – Traditions, Halloween, Wicca | HISTORY.” HISTORY, https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/samhain. Accessed 26 Sept. 2023.

2Rajchel, Diana. Samhain: Rituals, Recipes & Lore for Halloween. Llewellyn Worldwide, 2015.

3 Ibid.

4 McCoy, Edain. Mountain Magick: Folk Wisdom from the Heart of Appalachia. Llewellyn Publications, 1997.

5 Ibid.

6 Richards, Jake. Backwoods Witchcraft: Conjure & Folk Magic From Appalachia. Weiser Books, 2019

7 “Alleged Witch Gets Four Years.” Wheeling Intelligencer, 16 July 1918, page 5. Wheeling, West Virginia.

8 “Alleged Witch Up In Court.” Wheeling Intelligencer, 10 July 1918, page 6. Wheeling, West Virginia.

9 “Witchcraft in Our Midst.” Wheeling Intelligencer, 9 Mar. 1922, page 4. Wheeling, West VIrginia.

10 “Tessie’s Column.” The Wheeling Sunday Register, 28 July 1929, page 38. Wheeling, West Virginia.

11 “Medicos Hear of Witchcraft.” Wheeling Intelligencer, 1932, page 3. Wheeling, West Virginia.

12 Kellar, Michael. “Witchcraft Is ‘Old Religion.’” The Intelligencer , 30 Sept. 1972, page 6. Wheeling, West Virginia.