Editor’s Note: Since the City of Wheeling took ownership of the Clay School in 2022, there’s been a lot of discussion about the opportunities available for the redevelopment of this site. To help inform this decision, the City partnered with real estate development consultant Tipping Point to release a survey on June 1, 2023, asking residents to share their opinions and insights to help contribute to the decision-making process regarding the Clay School’s revitalization. Once this survey was made public, it elicited a lot of attention from current and former Wheeling residents. One former Clay School student, Patty Ciripompa, felt so passionately about the preservation of the Clay School that she shared an essay with Weelunk to help readers understand the role that Clay School has played in her life and the lives of many other former students. We appreciate Patty for reaching out and sharing her story with us.

This is her story:

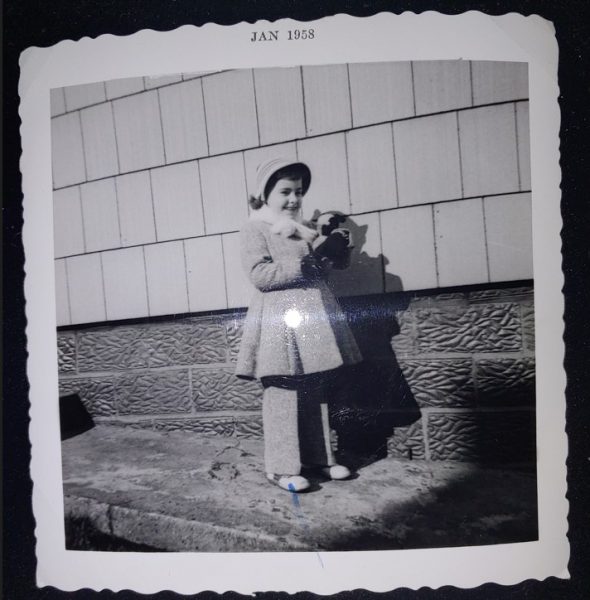

To a tiny five-year-old girl walking up 15th Street hill from McColloch Street, heading toward school for the first time in her life felt like an adventure. She walked with her right hand firmly gripped by her mother, cigarette smoke curling all around them through the crisp September morning air. She must have entertained at least a smidgen of a wish that they were headed downtown for that adventure instead of walking toward the great unknown. Doubtlessly, the butterflies she felt began to flutter more chaotically in her stomach as the massive yellow-white building came into sight. Bathed in early morning sunlight, the sprawling three-story giant must have seemed like one of those New York City skyscrapers she’d seen on TV. Her thoughts, being thoughts of a five-year-old, most likely did not make note that this glorious building would play such a pivotal role in shaping the woman she would become.

Clay School, the sunlit building that welcomed her on that first day, was conceived in a time of disorder and scarcity and born when a war was raging, and boys from the neighborhood were heading overseas in droves. For over fifty years, the Grande Dame of Fifteenth Street, with her sprawling girth that took up a city block, unpretentiously assumed the role of matriarch of East Wheeling. Her checkerboard-tile floors of burgundy and black welcomed the pounding of small feet from the moment her doors swung open and throughout her reign as a hub where hundreds of children from working-class families could come to learn and grow. Until her final bell rang, and her doors were opened for the last time, Clay School served as a loving steward for East Wheeling students.

Like ample arms spread wide, her honey-yellow block walls held wooden lockers that didn’t look like wood, their contents always a mishmash of forgotten lunches, crumpled papers, and hand-me-down books scrawled with every name who had held them throughout the years. Absorbing every voice of every decade, these same walls held the secrets that may have been whispered or wished, making her a keeper of the sacred passage of youth.

Her students were the children of her former students, who were often the children of students who came even before them – and her teachers stayed for years and became either worshiped or vilified, depending on who was asked. In the early 1950s, when the nation began to open minds and hearts to integration, she welcomed students of all races from all ethnic backgrounds. It was during my first-grade year that I was introduced to and became fast friends with other children whose skin color was darker than mine. As five and six-year-olds, we were blissfully unaware of any differences between us, enjoying instead the camaraderie of learning and playing together. In hindsight, these friendships that lasted beyond my grade school years shaped my view of the world, instilling within me the capacity to accept, embrace, and learn about others who may appear – but are not – different from me.

Our school’s playground was 15th Street, the entire block barricaded with wooden horses at either end. We thought it was the most wonderful playground in the world – a city street we could play on without worrying about getting run over. Every day, when the lunch bell rang, students headed to the spacious cafeteria, the ‘cold lunch’ room or, for some in junior high, down the street to Joe’s, where French fries eaten directly from a greasy brown paper bag tasted like Heaven. The cold-lunch room, located at the bottom of the first set of stairs off the entrance to the elementary grades smelled like bologna. Directly across from this room was the teachers’ lounge, so that when both doors were opened at the same time, the stairwell and hall smelled oddly like bologna smoking a cigarette. Despite the expected complaints and whines of children who rolled their eyes at what was served in the cafeteria on any given day, the hot lunches eaten there may likely have been the only warm meal of the day for some of the students. No child was turned away from eating in the cafeteria – free lunches looked exactly the same as those that were not free and no one knew the difference.

For reasons unknown to students at the time – but recognized in later life – most teachers who were attracted to jobs at Clay came with an authenticity and sincere desire to mentor and make a difference in the lives of the children they taught. I don’t remember all the math, or science, or geography in detail, but I have fond memories of many teachers, and how they made me feel seen, appreciated, capable, brave, valued and hopeful. These are the gifts I took with me into high school and beyond.

More than a building, Clay School has served as the protector of East Wheeling, watching over the neighborhood for over a quarter of a century. Her strong bones hold the essence of all the students who graced her halls, and her bricks bear the invisible imprints of all the hands that touched them. Selfless, she has given so much to us throughout the years. It’s her turn now to be honored and protected.

Patty attended Clay School from 1957 through 1965 and eventually went on to graduate from Triadelphia High School in 1969. While Patty no longer lives in Wheeling, she says her heart has never really left. She hopes to see the Clay School preserved and put back into use for the benefit of the community and encourages current Wheeling residents to have their voices heard by taking the Clay School Community Survey, which is open through June 30, 2023.