Originally published July 22, 2019

There are only two kinds of pizza, good pizza and very good pizza.

— Peter Reinhart, author of “American Pie, My Search for the Perfect Pizza”

Ask just about any Ohio Valley resident, and they will affirm DiCarlo’s falls into the very good pizza category. They may quibble over which location they prefer and the nuances of crust and cheese at particular locations. However, there is no doubt that DiCarlo’s is an iconic symbol of Wheeling culture.

Wheeling residents have nearly as much pride for the hometown pizza as they do for their hometown itself. As our city celebrates its 250th anniversary, Original DiCarlo’s Pizza celebrates 70 years of business in Wheeling, and the original location in Steubenville celebrates 74 years. This year also marks the 100th birthday of Galdo DiCarlo, patriarch of the franchise and co-inventor of the recipe. Galdo passed away in 1994, but his legacy continues through the work of the family and the legendary pizza he and his brother Primo created.

The DiCarlo’s story is a familiar American pizza story. Primo, the older brother, served in the military during World War II and was stationed in Italy. When he took his first bite of thin Italian bread covered in sauce and cheese, he likely had no idea where it would take his family in the future.

The DiCarlo family had emigrated from Sora, Italy, in the late 19th century, eventually settling in Steubenville. By the time Primo left to serve in the war, the DiCarlo family bakery was a popular spot in the community. They handcrafted everything from loaf bread to cakes to cookies to donuts — everything except pizza.

Neither brother was keen to join the family business, according to Galdo’s daughter Anna DiCarlo. “It’s grueling work, up at 3 a.m. every day of the year. It takes a special passion for that kind of work, and Dad wanted something different than to be a baker.” Primo saw pizza as a way to stay connected to the family tradition and pursue a business unlike anything else in the valley at the time. Galdo followed him in this venture.

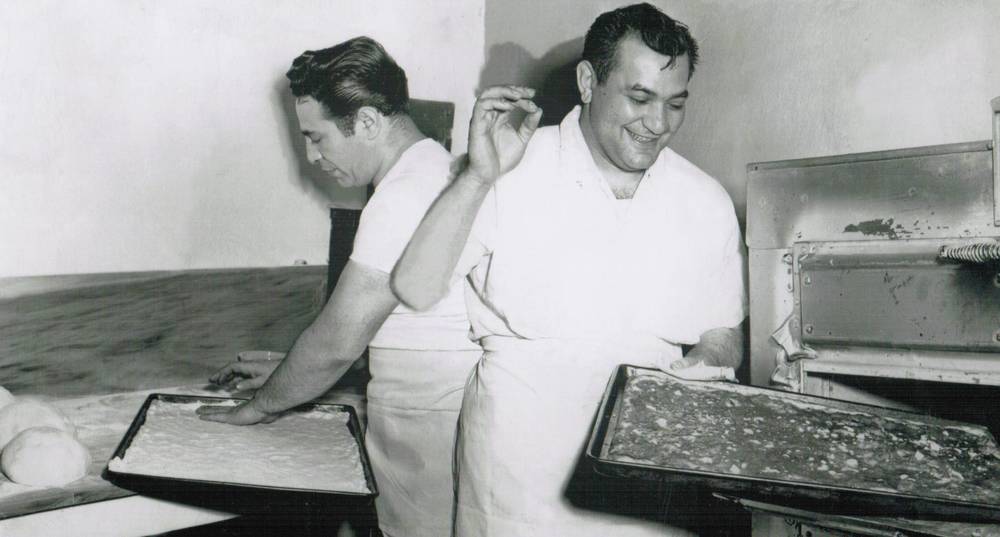

The recipe was perfected on borrowed cookie trays from the bakery. The cookie trays are critical to the story. Those trays are responsible for both the rectangular shape of the pie we enjoy and, more importantly, it led to serving the pizza with cold cheese and toppings.

“They used the family bread recipe for the dough; our family bakery had a reputation for great bread,” Anna said. “But when they baked it in the tray with the sauce and full cheese, the crust became too chewy, so the cheese and toppings came after the bake.” Cold cheese and that impeccably crunchy crust are the hallmarks of the DiCarlo’s pizza experience.

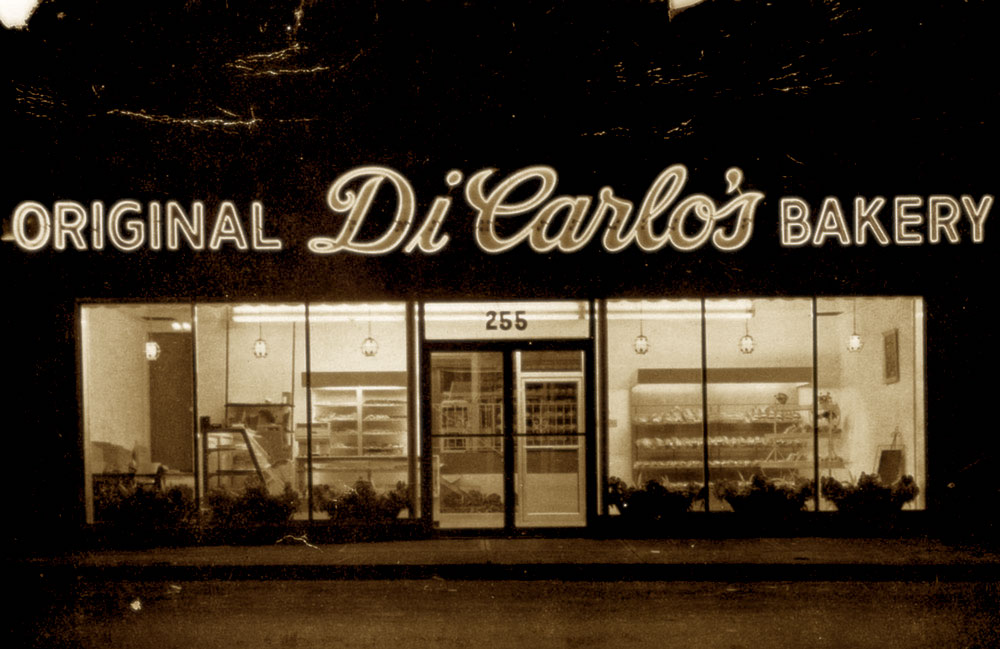

Primo launched the Steubenville location in 1945. A few years later, Galdo crossed the river and conquered “The Panhandle,” operating stores in Weirton, Wellsburg, Wheeling, Glen Dale and Elm Grove. It was the store on Main Street in Wheeling that came to be the flagship store locally, the one that created so many memories for Wheeling’s citizenry. Primo remained with the Ohio stores in the Steubenville area.

Today, the Wheeling area is operated by Galdo’s other daughter, Toni DiCarlo, and her son, Christopher. They operate the downtown store, and the Dallas Pike and Glen Dale locations. Anna operates the corporate stores and, along with her sons, David and Nick, she has overseen the expansion of the DiCarlo’s brand across four states and multiple locations. The Steubenville area is operated by Primo’s grandson who also bears his name.

IMITATION SINCEREST FORM OF FLATTERY

There are at least a half-dozen other pizza shops in the valley that serve an iteration of DiCarlo’s-style pizza. Anna attributes this in part to her father’s kindness and keen business sense.“He also ran a commissary for restaurants; he sold to other pizza shops the same tomatoes, cheese, flour that he used. It was part of his business model to be a supplier of high-quality ingredients,” she said.

At the height of Galdo’s run of the business, trademarking and franchise licensing weren’t so commonplace. It was easy for other shops to piggyback on the DiCarlo’s brand. A lot of those shops were operated by people who had worked in the DiCarlo’s kitchens at some point and moved on to start their own business.

A search for cold-cheese pizza on the Internet turns up only two other locations outside of the immediate Upper Ohio Valley. There is Tino’s, a shop in Oneonta, New York, that serves round pie with cold cheese, and Beto’s in Pittsburgh, which looks remarkably like DiCarlo’s. In 1951, DiCarlo’s opened one of its earliest locations on Saw Mill Run Boulevard in Pittsburgh.

STAYING TRUE TO RECIPE

Tim Morris began working at the Wellsburg DiCarlo’s in 1981 at the age of 16. Four years later, he bought the store and, in the 34 years since, he has taken 12 vacation days. Why only 12 days in 34 years? Because he is a zealot for making pizza the DiCarlo’s way.

He learned the recipe from Mike Travato, a contemporary of Galdo. When Galdo launched the Wellsburg location in 1973, Travato became the manager; he later bought the franchise. They have been slinging DiCarlo’s pizza in that same building ever since.

Each morning, Morris arrives and makes the sauce from scratch, kneads the dough and preps the rest of the toppings. “We make everything by hand, exactly the way I was taught by Mike. Nothing arrives at this store pre-made; we cut, we slice, we knead everything right here in the kitchen.”

Anna simply loves Tim’s commitment to the family recipe. “DiCarlo’s isn’t fast-food pizza. It is an art and craft. It requires attention to detail and appreciation for our family history. Tim has never strayed from the details.”

Morris says he buys the same tomatoes, same flour and prepares it the way it has always been made because the customers know when something is amiss. He recalls a number of years ago the pepperoni supplier he had used for decades went out of business, and he was forced to change. “The shop phone rang for weeks with people asking why we changed the pizza; it was the end of the world.” He says this style of pizza is special to the people of this valley and it can’t be tinkered with — even slightly.

SPECIAL DELIVERY

Joan Carrigan of Wheeling may hold the prize for longest delivery. She has delivered DiCarlo’s pizza around the world to her four children. Carrigan has carried it to Germany twice, shipped it to Alaska and just recently carried a tray of pizza in her luggage to her daughter and husband in San Francisco.

Her son, Rick, and his wife, Eileen, are an Air Force family and were stationed in Stuttgart, Germany, for a number of years. Carrigan says she froze the pizza, wrapped it in foil and stuffed it in her luggage. She said because the luggage went into the cargo compartment, it stayed mostly frozen until they arrived at her son’s home.

In Alaska, they don’t leave packages at mailboxes or doorsteps because of bears and moose; they just leave a note that the resident has a package. When the Carrigan’s pizza package arrived in Alaska, no one was home, so a note was left. Carrigan recalls needing to sternly encourage her daughter to go pick up the package the day it arrived. “I didn’t want to ruin the surprise, but didn’t want to ruin the pizza either; she was glad she went to pick it up that day.”

COLD CHEESE GOING MAINSTREAM

The beauty of pizza is its simplicity. Its core ingredients of bread and sauce allow for just about any culture to reimagine it into something that is purely local. In some instances, this local style of pizza becomes a regional or even national sensation.

Anyone who pays attention to pizza knows a New York slice when they see it. Chicago has its deep dish. Even Detroit-style pizza, with its little tray from the automotive industry, has become “a thing” in the culinary world. So, could Ohio Valley cold-cheese pizza become a thing, something the whole country comes to recognize when they see it and associate it with a place on the map?

According to David Sax, author of The Tastemakers, it’s not out of the question. He says there are certain foods for which we have a perennial appetite. “Pizza is one of those comfort foods that never goes out of style and, because it is perennially available, we are always looking for a new variation on it.”

He says it’s the constant availability of pizza that actually creates a space that allows a new variation to be sensationalized. To become not just dinner, but dinner conversation. He cautions there are a few key principles to keep in mind.

First, does it really taste good? CHECK. We know DiCarlo’s is rocking. We have 74 years of evidence as proof. Sax says in this age of Instagramming food there can be overnight social media sensations that people quickly find out don’t taste good (remember rainbow unicorn sparkle lattes? It’s better we don’t). We know DiCarlo’s has a “taste benefit” for the consumer and, Sax says, because it has been copied locally, it has the potential to catch fire in other places.

The second question in this trendsetting agenda is are the ingredients readily available? CHECK. CHECK. While DiCarlo’s prides itself on using high-quality ingredients, none is rare. It’s not goji berry pizza. What really makes their pizza different is the order in which it is assembled and that tray — remember that cookie sheet tray. Sax says readily available ingredients are key to creating a definable trend; there needs to be the ability to replicate the recipe year-round in various locales.

The third principle is breaking into a market where the national media might discover that “hey, this cold-cheese pizza is a thing, we better cover this.” He calls that the X-factor, the one that is nearly impossible to control. It could be a famous chef taking the idea and putting it on the menu in a swanky restaurant location. Or it could be that a local tourist destination (think Oglebay) becomes a super hot national vacation spot, and people from across the country develop a taste for the unique pizza and want it at home, year-round.

For DiCarlo’s, they are well on their way to finding a larger audience. The DiCarlo’s brand has an ever-expanding list of franchise locations. From York, Pennsylvania, to Columbus, Ohio, to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, “cold-cheese” pizza made the Ohio Valley way is inching its way around the country. Locations in Akron and The Short North in Columbus open later this year.

Sax says in the end, it’s really about a particular food having a great story. “The story is the real vehicle that can capture the imagination.” DiCarlo’s has the story: the family bakery, the war, the two brothers, now the two sisters and family, copy-cat pizza shops, around-the-world deliveries, that cookie sheet, cold cheese. The story is there — we as a community just need to keep telling it.

Photos courtesy of the DiCarlo family and franchisees