Editor’s note: Last week, Anne Hazlett Foreman shared Echoes … Of Life Below Violet Hill. Today, we read about life on top of Violet Hill.

Of course, the first game of kick the can was too tempting for me not to spill the beans. I pointed to the house above Birch Avenue and said, “I’m going to live there soon.”

No one believed me. Three weeks later, we spent our first night in the house on the hill.

There were seven houses in Echo Point Circle at the time. Most were grand Queen Anne Victorian in style and were arranged around the edge of a huge green space in the middle. Originally the Dewey property, the oldest home had been built in the middle of the circle and, at some point, moved to the edge and became No. 6 Echo Point. It was right next door to us. We had the “youngest” house, built around 1910; it was stucco with a red tile roof, very exotic — even European — compared to the others.

My grandmother, aunts and uncles owned homes there as well. Our purchase rounded out the family “circle,” so to speak. We were as thick as thieves and resembled the legendary compounds in Jersey mafia lore, without the bodyguards or guns. We lived within feet of everyone in the family. Five cousins lived next door. Sunday dinners, all year ’round, at our grandmother’s home were a given.

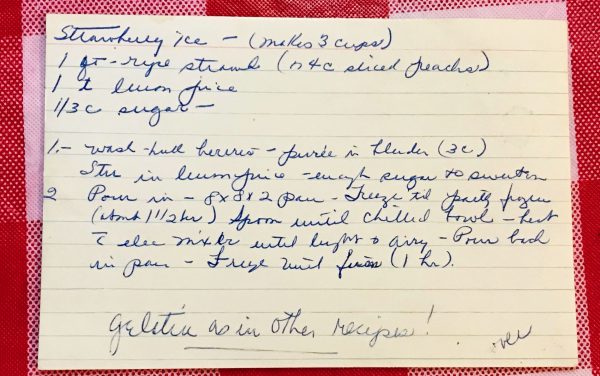

In the summers, we had softball games with all ages running the bases. Homebase was in the big field across from my grandmother’s house at No. 3. Most of us hit balls that stayed in the bounds of our grassy area, but occasionally, they would be lost on the hillside on the other side of the road, and the game would be over. After the games, we gathered on Mimi’s front porch to have a traditional favorite, her famous “ices.” They were made from fresh fruit and could be strawberry, pineapple or peach. Deliciously and unabashedly sweet, they were neither sherbet nor ice cream.

DARK SHADOWS

I don’t remember packing anything for the big move a block away. I may have been farmed out for that process, but I do remember the musty smells and the echoes in the empty rooms that met us as we entered the large front hall for the first time.

It was fall, and dark shadows added to the eerie quality of the whole house and grounds. The steam heat coming on in the first cool days alarmed us with the knocking and banging as the iron radiators heated up. I never really got used to that sound.

My sister and I had our own bedrooms, but we were too afraid to be apart, so we huddled in my room at the front of the house for weeks after moving in. We heard noises in the night — night after night. Reassurances from mom that they were just traffic sounds from cars on Chicken Neck Hill didn’t help too much. However, eventually, we became used to the car sounds or soulful pleas from spirits right outside our window, whichever. I think we remained convinced the house was haunted, even when we got older. No one could explain the footfalls we all heard on the big staircase at night. Old houses make noises, and the steps were not carpeted, but no one could convince us there were not ghosts about.

The house was designed in a sort of rambling manner that clung to the top of the hill and looked a bit like an Italian villa or a beached warship, if viewed from below. It was long and narrow with a great hall and staircase that wandered up the left-hand side. To the right of the downstairs hall, in a gracious open floor plan, were three rooms in a line — the front living room, middle room and dining room. The kitchen and breakfast room were in the back of the house, and my father’s library adjoined the middle room. There was a lovely terra cotta terrace that ran from the front of the house to the very back. Mother kept the formality of the downstairs intact.

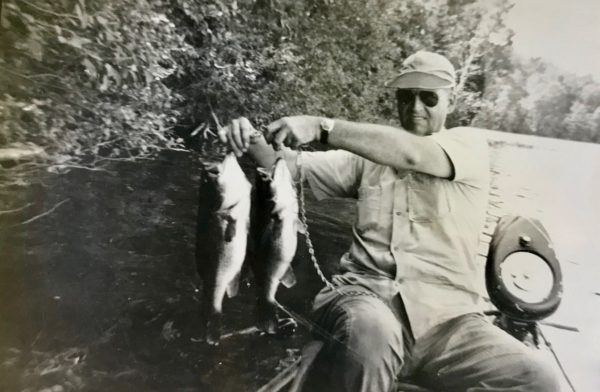

We used one of the many bedrooms upstairs as a family room. There was the TV, dad’s drafting table where he tied his own flies for his fishing habit and lots of comfortable chairs.

My father dove into anything he undertook with an enthusiasm and energy that was legendary. When he tied his fishing flies, he used deer hide from Herter’s catalog, which came in pieces with fur attached and got quite “ripe” if not used right away. His flies were ornate and well-researched. He loved to cast a line and practiced in the large grassy meadow in the middle of the Circle, as it was known. He used one of our Hula Hoops to practice and became quite good at hitting the inside of the round plastic target. His movements were graceful and fluid. Favorite fishing spots were Deep Creek Lake (before the powerboats took over), the Trough in the South Branch and sometimes Canada.

Our home had been built around the turn of the last century and was gracious in a Gatsby sort of way. I have seen old photos of a wedding reception on the terraces — I think it was a member of the Round family, who lived there at the time.

There were five large bedrooms on the second floor that opened onto a hallway that ran the entire length of the house. The front three bedrooms overlooked the stairs and hall below. There was a bank of stained-glass windows and a window seat halfway up the stairs and, hanging from the high ceiling over all, was a black wrought iron light fixture. In the bat summers, which was every summer, the winged creatures would circle that huge lamp, looking for all the world like a Charles Adams pen-and-ink cartoon.

The servants’ quarters were on the third floor. There were three large bedrooms and a bath up there and plenty of storage for the linens and anything else not kept on the second floor. The in-house firehoses were fascinating. They were kept on each floor, wrapped like a coiled snake on the walls. They were old rotten canvas things with brass nozzles. Then there was the whole-house vacuum system that we never used. Intercoms on every floor — even the basement — were evidence of the presence of a large staff when the house was in its glory. The dumbwaiter running from the third floor to the basement was big enough to ride in. For many reasons, including the fact that my father was a physician and mom a nurse, it was off-limits to us. Their visions of one or all of us falling three stories down the shaft, large enough to hold us all, was enough to squelch our fun. It did make an awesome clothes chute.

DOWN UNDER

The basement was terrifying — at least some of it. Half of it was a typical basement, but with very high ceilings — laundry room, storage room and changing room for the swimming pool. Part of the “normal” basement was a garage that was located below the back terrace. It was huge, as was the scale of everything else in the house, and had a gasoline tank and grease pit in it … all the comforts and accessories of a home with a chauffeur on staff.

Then there was the dungeon. To the right at the bottom of the steps, opposite the normal side, which was to the left, past the root cellar was a door. Behind it stretched a series of dark rooms and, at the end, was the furnace room. It was everything one has heard about the Bastille, only worse. Single light bulbs dangling from the ceilings in cavernous rooms provided the only light. There was a cement pathway that led to that last room. The floors otherwise were dirt.

In our adolescent minds, we were sure that torture and possible murder had taken place in that furnace room with its huge boiler. No doubt about it. The incredibly high, two-story ceilings in the basement only added to the “ ambiance.” Everything was dark red brick. Only the chains with manacles attached and flaming torches driven into the walls were missing.

In our adolescent minds, we were sure that torture and possible murder had taken place in that furnace room with its huge boiler. No doubt about it. … Only the chains with manacles attached and flaming torches driven into the walls were missing.

Our mother, always resourceful and practical, used the dirt floors in one of the darkest rooms to grow mushrooms. It was quite successful.

Then in the ’60s, the basement’s role changed, dramatically.

After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the extended family, who all lived in houses in the Circle, got together and decided to build a bomb shelter. In our basement. My family did things thoroughly. Research was done — wall thickness, baffles, number of water tanks, guidelines for what kind and how much canned food — everything was studied and tweaked to accommodate 20 people. Our basement was already a fortress, with walls 2-feet thick, and was the obvious place to construct the shelter guaranteed to protect from deadly radiation. The other family homes were wood Victorian treasures; ours was the newest and was brick and stucco. The success of this messy and expensive venture all hinged on not being at ground zero when the bomb dropped, but I digress.

What had looked good on paper soon took form in less than a year’s time. Dirt floors were covered with cement; concrete blocks and mortar added another required foot to the wall thickness. Aunts, uncles and parents proceeded to erect a state-of-the-art home fallout shelter. Two water tanks were installed, canned food and infant formula were stocked (no babies at the time but formula would sustain all if other food ran out), and cots were bought. It was done at last. Fearing instant incineration at any time or suffering the effects of radiation poisoning was not the best way to spend my teenage years, but 200 years before that, settlers on the very same land feared instant death as well. There’s always a “devil at the door,” just in different clothing. Uncomfortable questions posed to our parents, such as, “Would we let friends in?” would be dismissed after awkward pauses and, fortunately, didn’t have to be tested.

EVERYBODY IN … THE WATER’S FINE

The swimming pool was ancient — installed when the house was built. It had not been used for many years and had to be cleaned, painted and refitted with a modern filtration system, skimmers and a vacuum, the latter both kid-driven and had to be done before anyone got into the pool. Plastic liners didn’t exist then, and most pools were poured cement, paint having to be refreshed every year.

The very first such session took place on an unusually hot spring day. The sun was full on the pool, and mom, brother Jim and I attacked the job with rollers and aqua paint, which got all over everyone. The fumes from the oil paint plus the heat soon overcame us, but we persevered eagerly anticipating the very first swim, which happened the next week. I was in the pool whenever there was someone else to go with me, as, of course, we were never allowed to swim alone.

There were large spotlights mounted on the upper story of the house, which overlooked the pool, and were so high and so big the fire department had to come to change them. While they cast a lovely soft light on the water, they also put a damper on any skinny dipping. Apparently, years later, we learned that most of the Birch Lyn teenagers had breached the fences and enjoyed our pool in the wee hours of the night at one time or another.

It was decided that the pool needed some sort of area around it that would prevent grass from getting in the water every time someone jumped in. Foot rinsing basins near the ladder helped a bit but not much. Some genius in the family came up with the idea of using marble slabs that were being removed from Wheeling Dollar Bank downtown during a renovation. The beautiful blue-veined pieces were placed all around the edges of the pool and looked elegant. The only problem was the marble was like greased lightning when wet. Children running slipped and bumped heads. Cement was poured shortly after that.

Five steps led from the pool up to a garden. It was in shambles when we moved in, and my mother soon threw her love and skill into rehabilitating it. It was roughly divided into four inner beds by a Celtic Cross series of gravel paths. There were four larger beds that defined the outer circle shape. My sister and I helped her line the beds with red bricks and weeded, it which seemed to be a constant task. There were mostly spring flowers, Iris being mother’s favorite.

Five steps led from the pool up to a garden. It was in shambles when we moved in, and my mother soon threw her love and skill into rehabilitating it. It was roughly divided into four inner beds by a Celtic Cross series of gravel paths. There were four larger beds that defined the outer circle shape. My sister and I helped her line the beds with red bricks and weeded, it which seemed to be a constant task. There were mostly spring flowers, Iris being mother’s favorite.

CHRISTMAS EVE MAGIC

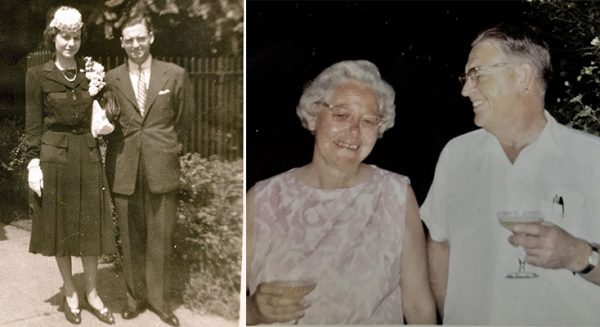

Christmas Eve was magic in the Circle. It had been my grandfather’s birthday and, even though he died in 1943 before I was born, my grandmother kept the tradition alive for us. The first celebration was the year she married my grandfather, 1909, and included the family as it was then.

In my time, she had the entire clan for a formal supper every Dec. 24. We all dressed up and gathered in the big, gracious house at No. 3. A family portrait was taken by a professional photographer, Mr. Schultz, whose patience was tested each year as he herded us into some sort of order. The tallest stood behind the couch, the oldest were on it, and everyone else gathered on either side, youngest on the floor.

The Old Fashioned cocktails were passed by the oldest male present — in my time, it was my grandmother’s brother, Thomas Cummins — and were carried on a huge metal painted tole tray. It marked a rite of passage when we were finally offered one. The Old Fashioned cocktails that my grandmother made were colorful and tasty, replete with crystal muddlers so the sugar cubes in the bottom of the glass could be crushed. They contained — besides the sugar cubes — bourbon, angostura bitters, orange liquor and maraschino cherries. It took two days for them to “ripen” — for the full flavor of the ingredients to develop.

The main dining room table was joined by smaller ones scattered throughout the livingroom and great hall. Turkey, with all the trimmings, and the family favorite, corn pudding, were on the buffet. Relish trays, salted almonds and buttermints were interspersed between the centerpiece and candles. Linens, silver and china graced all the tables, and everyone present had a full stocking hanging on the living room mantel.

In the 1950s, the family was smaller than it is now; my generation had not married and produced the next level of offspring. The tradition carries on today — thanks to my cousin Tom — not in a home because we’ve outgrown that, but at Oglebay’s Wilson Lodge, more than 100 years after the first birthday party.

As I grew up, the evening took on a different aura but never lost its magic. Fresh greens covered every doorway and mantel and filled the house with all the smells of an idyllic Christmas. The perfume my mother wore only on that night is my favorite one today and was aptly named Nuit de Noel.

My earliest memory was falling asleep on my father’s shoulder at the end of the evening, hearing voices blurring in the background and being carried out to the car. Years later, on Christmas Eve, I proudly showed my grandmother my engagement ring. I had accepted the proposal only days before. It was not a large stone by any means and, as if sensing my anxiety about that, my grandmother took my hand to admire it and said, “It has more fire than any diamond in the family.”

LOVES AND LOSSES

Most of the years spent at No. 7 were full of joy. We swam in the pool, had parties on the terrace, played ball, fell in love. We were blessed to have been surrounded by unconditional acceptance from a huge extended family. There were minor tiffs and the usual in-law nonsense, but overall, we were one.

There were fractures in this happy scenario, of course. My brother fell ill with “mono” —infectious mononucleosis — when he was a junior at Linsly. He was taken by ambulance to the Ohio Valley General Hospital and was admitted to the intensive care unit. This was in the mid-1960s. He was not expected to live. No one ever got that sick from mono. Prayers were said at his school, and my mother and father were at his bedside constantly. He pulled through with the grace of God, lost a year of school but managed to be second in his class nonetheless.

My mother fell ill with cancer in the mid-1960s. She started to slow down, to forget, to slip into a dementia sort of ritual that terrified us all. She had been the rock, the center, of our world. Mom was the caretaker of three difficult children, a devoted wife who encouraged my father to pursue not only his medical career but his many interests. She was sick, and we were lost. When dad started out in his medical practice, mom was his nurse when he couldn’t afford to hire someone. Later, she was his receptionist, then his bookkeeper and an office manager, in today’s language.

My sister was a freshman at Bethany College, I was living in a dorm at Linsly with my husband who was teaching there, my brother was at Ohio State getting his doctorate, and my father was facing this tragedy by himself in that big house. I went to sit with Mother every day. Dad would pick me up at 5 a.m., before his shift at the ER. I sat with Mother, day after day. She didn’t need nursing care at that point … she was pretty much bedridden, but I could take care of her needs until Dad got home.

One day, as I was sitting on a chair in her bedroom, sewing a button on a coat, my mother looked up at me, not really knowing who I was, and smiled sweetly. Hours later, she lapsed into a coma. Dr. Drinkard made the final house call and said there was nothing more to be done. The family members came one by one to hold her hand and say goodbye. As my grandmother left the house, she said to me that mom seemed to be at peace.

It was on Monday, Nov. 4, 1968, my mother took her last labored breath. Her children were all there, as was my father. A physician, he looked at the clock and pronounced death at 2:58 p.m. Her body was carried out of the home that she had loved and cherished late that afternoon.

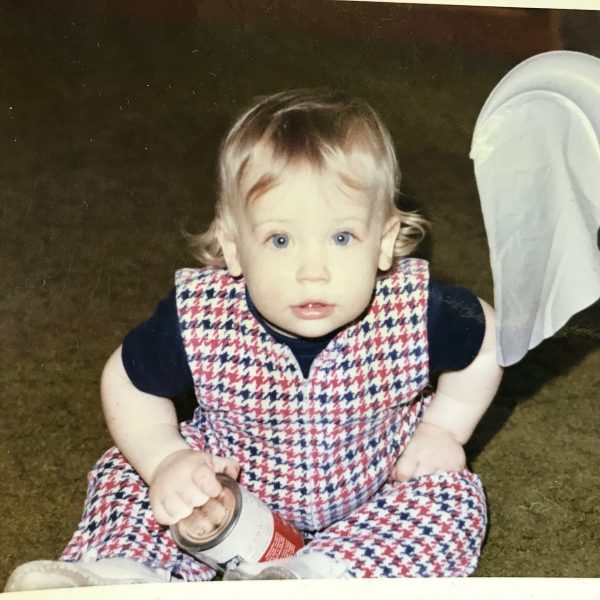

Almost a year later, also on a Monday, at exactly 2:58 p.m., Oct. 13, our first son, Sam, was born. After a week in the hospital, I came home to Echo Point with my baby.

It was a fall day, much like the first day I ever spent in that house many years before. My husband had gone back to Morgantown to law school, my father was on a 12-hour shift at the ER, and I was alone in that huge, empty home.

I was too afraid to go upstairs that night and spent the time between dusk and dawn in the little breakfast room off the kitchen.

Baby Sam and I cried together all night. I wept for my mother; he cried because babies cry. I did not know what to do. My grandmother, 83 at the time, had offered to come to sit with me. I was worried about her wellbeing and declined the gesture. To this day, I am sorry I didn’t let her.

I was 21 when I lost my mother. She never knew her grandchildren, and I never really knew her as an adult. It was a loss I have regretted all my life, but I realize I was blessed to have had her as long as I did.

• Anne Hazlett Foreman, an award-winning artist, has been a member of Artworks Around Town for 20 years, having been on the board for the first four years. She also has served as chairman of the Oglebay Institute Mansion Museum Committee; served two terms and was vice president of the West Virginia Independence Hall Foundation; served on the Oglebay Institute Board of Directors, the board of Fort Henry Days and the Wheeling Hall of Fame board; and is a member of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. Foreman is a graduate of Mount de Chantal Visitation Academy and attended Wheeling College and Chatham College. She is married to Robert Noel Foreman, and they have six children and several grandchildren.