In the early 1960s, every lawyer, judge, politician and policeman in the city of Wheeling knew Chris Cerone. He was the blind man who, from his busy snack stand at the Wheeling Ohio County Courthouse, served up Lance crackers, coffee, cold bottles of Coke, candy bars, potato chips and cookies, along with witty conversation – punctuated with a New York City accent — that touched on everything from sports to West Virginia politics. But Chris was much more than that, especially to the Griffith family.

To every politically active blind person in West Virginia, he was president of the West Virginia Federation of the Blind – a leader, spokesman and hero in fights against discrimination and narrow-mindedness. He used an uncanny knowledge of the Roberts Rules of Order to get things done in formal meetings of the Federation and an aggressive personality to represent the organization in the halls of the legislature.

To every teenager who loitered, loafed and danced weekend nights away in Tom Minns’ South Wheeling confectionaries in the 1930s, he was remembered for his musical talent, jolly demeanor and willingness to offer life advice.

To people who kept a well-tuned piano in their Wheeling parlors in the 1940s, he was the man who kept their instruments in tip-top shape.

To my family, he was loved as a wise mentor, gentle friend, supporter of dreams and surrogate grandfather to my brother, Terry and me.

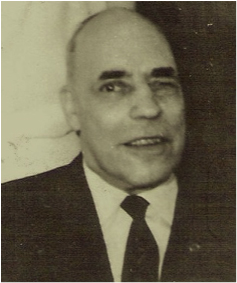

He wasn’t very tall, had a shiny, bald head with a fringe of gray hair on the sides that he kept very short, and he was kind of doughy in build, not skinny but not fat either. He had classic Italian looks punctuated by an oversized nose. He never used dark glasses to mask his blindness. He always wore open-collared short-sleeve white shirts with no necktie, with blue or brown dress pants, and he always carried a heavy, white cane that he used to safely negotiate the streets of Wheeling. A life-long bachelor, Mr. Cerone lived at Wheeling’s YMCA for almost 30 years.

In the 1960s, I was a gimpy, chubby, child being raised by two women in Elm Grove. My father passed in 1955. Mr. Cerone stepped in. He drew my mother, Mabel, and my grandmother, Lizzie, who lost her husband in 1951, into the work of the West Virginia Federation of the Blind, providing them with an avenue for their successful re-entry into society after a period of painful mourning. My mother had mad typing, organizational and support skills that she put to effective use as Mr. Cerone’s able assistant on Federation business. On many Saturday nights, Mr. Cerone would sit at our dining room table and dictate letters and memos, and my mother would type them out on her old, portable Underwood.

He supported Terry’s budding interest in music, bringing him sheet music and plenty of kind words of encouragement. The two spent hours sitting on the piano bench in front of the keyboard as Mr. Cerone, the consummate musician and teacher, explained the complexities of music theory – the study of the elements of music like sound, pitch, rhythm, melody, harmony and notation.

“He taught me more about music theory than I learned as a music major at West Liberty,” Terry, who has been a performer and songwriter for more than 50 years, said recently. “I consistently use what he taught me, and I never used anything else I learned in school.”

Every so often, Mr. Cerone would treat us to a boogie-woogie piano performance on the beat up old upright instrument my grandmother bought second-hand and had installed in the basement in the hopes that the piano lessons she paid for me to take would someday pay off – they never did.

For me, he was the wise and kind family friend who would slip me quarters, give me pep talks when I was down, and dazzle me with stories about history, music and his beloved Wheeling Ironmen football team.

Occasionally, I would come home in tears over some slight I perceived I had suffered at the hands of the neighborhood kids’ teasing cruelty. Ifhewas visiting, it was always Mr. Cerone who would pull me aside and assail me with logic and understanding to calm my hurt feelings and bolster my spirits to return to the outdoor fray.

The special time I spent with Mr. Cerone always occurred on Saturday nights when I would meet him at the bus stop at the corner of Columbia Avenue and Kruger Street. It was when I had him all to myself without interruption from adults. My assignment was to meet him and, as I had been trained to do with all blind people, offer him my shoulder as I guided him down the sidewalk to our house on Columbia Avenue. We must have been a sight – a tiny little boy leading a big, older blind man holding a thick, white cane gingerly down the sidewalk around obstacles and chatting a blue streak all the while.

It was an important job because the sidewalk was a treacherous obstacle course for a blind man. There were deep cracks in places, and in some locations, tree roots had forced their way up through the concrete to create peaks and valleys on the surface that even sighted people tripped over. And then there were the bikes and tricycles and skates and toys that the many neighborhood children would leave on the sidewalk. Upon our safe arrival to the house, Mr. Cerone would push a bright shiny new quarter into my tiny palm – a masterful sum in 1962.

Mr. Cerone, or Chris, as only my grandmother was entitled to call him, had been a part of our family for decades. He met my blind grandparents when he was a teacher at the West Virginia School for the Blind in Romney, and they were on campus to participate in an alumni association. When budget cutbacks at the school caused termination of his teaching job, Mr. Cerone was invited by my grandparents to move to Wheeling and start a new career. He stayed with them for two years in their apartments/confectionaries all over South Wheeling before eventually moving to the YMCA where he would live for the rest of his life.

He made a good living by tuning pianos all over the Ohio Valley. If you could pay his fee and help with transportation, he would make your piano pitch-perfect.

By the early 1960s, he altered his career to take over the concession stand at the City/County Building. Mr. Cerone beamed with pride when the new Wheeling/Ohio County Courthouse opened in January 1960. My mother took my grandmother and me to the grand opening and tour. Mr. Cerone’s stand, just inside the Chapline Street entrance, was state-of-the-art with a wide Formica countertop and strategically placed product racks. The smell of his freshly brewed coffee wafted throughout the first floor of the government building from a huge silver canister pot. His business was a gathering point for men and women in the courthouse. It quickly became known as the place for a quick snack and a kind word.

One sweltering summer evening in 1964, Mom, Grandma and I piled in our Dodge Dart, and we drove downtown to pick Mr. Cerone up for a drive down to Moundsville to visit another blind couple. I hopped out of the car, ran up the marble steps of the ornate YMCA building that is now Maxwell Centre, and said hello to Mr. Cerone, who stood at the top of the steps waiting. As usual, he placed his hand on my right shoulder, and I led him down to the car.

“Hello, Lizzie. Hello, Mabel,” he said calmly.

“I think we need to change our plan. Can you run me up to the emergency room? I’m having a spell.”

Ohio Valley General Hospital was only blocks away, and my mom drove faster than I’d ever seen her drive before. Mr. Cerone was having a heart attack. His breathing was labored, he was perspiring heavily, and he held his right hand close to his chest in obvious discomfort. I remember him opening the back-seat door and turning to my grandma with a smile on his face.

“Thanks, Lizzie. Sorry for changing the plans.”

I will always remember that smile and how confused I was as a 10-year-old that he seemed cheerful in the face of the emergency. He got out of the car and walked, holding my mom’s elbow, into the emergency room.

I never saw Mr. Cerone again.

He was 61. The call from the hospital came in the middle of the night and was met with much weeping by my mom and grandmother. My broth er and I were stoic in the face of the news. I don’t think we knew exactly how to act other than to be supportive of the women who were raising us. We hugged them tightly and listened to their grieving tales of Mr. Cerone’s kindness all while processing our own private thoughts about the loss of an important mentor and friend. Mom and Grandma are gone now, and Terry and I are older than Mr. Cerone was on the night he passed.

er and I were stoic in the face of the news. I don’t think we knew exactly how to act other than to be supportive of the women who were raising us. We hugged them tightly and listened to their grieving tales of Mr. Cerone’s kindness all while processing our own private thoughts about the loss of an important mentor and friend. Mom and Grandma are gone now, and Terry and I are older than Mr. Cerone was on the night he passed.

Not long ago, I took a Friends of Wheeling tour of Greenwood Cemetery where Mr. Cerone is buried. Local people portrayed famous and infamous persons from Wheeling’s past who are interred there. Although well-known in his time for his courthouse snack stand, work on behalf of sightless people, his outgoing personality, outstanding musicianship and overall kindness, Mr. Cerone will never be the subject of one of the stops on the Greenwood Tour. There is no information about him on the Internet. No awards or accolades are posted in tribute to him on public buildings. Yet, He was a true Wheeling personality and worthy of the memories we keep.

• Gerry Griffith was born and raised in Wheeling’s Elm Grove section. He pursued a career in journalism before working on Capitol Hill for then-Congressman Alan Mollohan in Washington, D.C. He returned to Wheeling and stayed nearly 20 years to work at Wheeling Jesuit University, Touchstone Research Laboratory and in Congressman Mollohan’s Ohio County office. He also worked for the West Virginia University Research Corporation. He currently lives near Pittsburgh where he works at the National Energy Research Laboratory. He is also a contributing editor to a national industrial research publication and dabbles in fiction writing.