Editor’s note: As part of a continuing series on how Wheeling residents express spirituality, today’s post features Orthodoxy, an ancient form of Christianity whose worship has remained virtually unchanged since the Byzantine era.

Somewhere in the world, incense is wafting. A chalice is waiting. And, a priest is softly speaking a prayer that has been offered hourly for more than 1,600 years: “It is proper and right to sing to you, bless you, praise you, thank you and worship you in all places of your dominion …”

Somewhere in the world, incense is wafting. A chalice is waiting. And, a priest is softly speaking a prayer that has been offered hourly for more than 1,600 years: “It is proper and right to sing to you, bless you, praise you, thank you and worship you in all places of your dominion …”

The actual words might be in Greek or Russian or Arabic, but right here in Wheeling, Father Demetrios Tsikouris is quite comforted by that kind of continuity of spirit.

“The Divine Liturgy is everything to the Orthodox Christian who’s participating properly,” said Tsikouris, pastor of St. John the Divine Greek Orthodox Church in the downtown. “The center of the Orthodox worship and spiritual life is fashioned after what we would call the heavenly worship.”

Based on tantalizing glimpses of heaven’s throne room revealed in scriptures found in such books as Isaiah and Revelation, the chanted prayers and scriptural readings of Orthodoxy are meant to do more than replicate, he added. “We are mystically entering into that heavenly worship.”

Adding to that effect, Tsikouris sings or intones much of the service per Orthodox tradition. Congregants sing back such words as, “Holy, holy, holy, Lord Sabaoth, heaven and earth are filled with your glory. Hosanna in the highest.”

That back and forth, that mystical entering in is the point, he said. “We’re all working together.”

ANCIENT YET RELEVANT?

Do words of antiquity fly in an America that seems increasingly geared to the uber-contemporary worship favored by mega churches? Tsikouris, who left a professorship of pharmacology at University of Pittsburgh to pursue the priesthood, says they do.

St. John’s is home to not only the descendants of Greek immigrants and Orthodox Christians from other parts of the world, but to newer converts who have been drawn by that very history and spirit of the sacred. The converts include Shelly, his wife and mother of the couple’s four daughters. She grew up in a Baptist family.

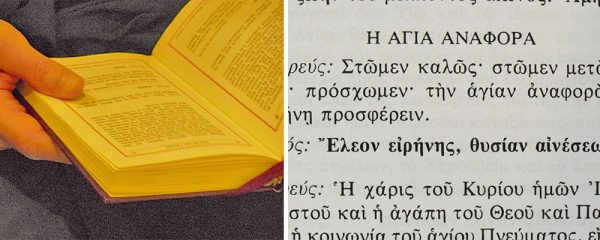

So, the tradition goes on. Incense instead of coffee in the pews. Hand-held liturgical books (written in both Greek and English) instead of words projected onto a drop-down screen. Byzantine-style chanting and intonation instead of electric guitars and drums. The latter, in fact, seem almost laughable in a church that glows as if carved from ivory and carries a hint of spikenard incense from Sunday service.

“It’s the same way people would understand it’s wrong if they came upon me drinking my morning orange juice out of the holy (communion) chalice,” the Youngstown, Ohio, native explained of maintaining at atmosphere that is set apart from the ordinary. “I know how to use PowerPoint … But, it’s not supposed to look like a classroom or a concert. It’s sacred.”

And, forget in-and-out timing, he added. The typical Sunday Orthodox service lasts about 90 minutes. Certain services of Lent and Holy Week blossom to as much as two-three hours long and six times per week as Easter nears.

“They are designed to prepare a person to meet God,” Tsikouris said. “Not to suit a person, but to change a person.”

This adherence to Orthodoxy or, literally, “proper glory” is far from grim, however, he added. He said services have a big dose of joy. He particularly enjoys worship during Lent, the season of reflection and repentance that precedes Easter, even though that much chanting and intonation takes its toll on his voice.

“They don’t realize that I’m dying by the end of the week,” he said, both laughing in anticipation of the coming season and noting he actually prefers the lengthy Lenten prayers written by St. Basil the Great.

BEFORE AND AFTER

For all its commitment to antiquity, Tsikouris explained that Orthodoxy shares certain elements with the Roman Catholic Church and other liturgical forms of Christianity. Indeed, he said, Orthodoxy and Catholicism could be said to be Eastern and Western expressions of Christianity’s shared first millennium.

Both expressions revere communion, or the Eucharist, literally “thanksgiving.” Tsikouris pronounces it in Greek, a whispery eff-kar-EES-tee-uh that still manages to echo around the church.

Services and priestly customs such as facing the altar rather than the congregation during parts of the liturgy also have commonalities, particularly if looking at Catholicism prior to the second Vatican Council, he added.

There are critical differences, however. Tsikouris said disagreement between Eastern and Western Christianity ranged from authority structure (Orthodoxy has a council of bishops rather than a pope) to doctrine (such as one split-provoking difference being the procession of the Holy Spirit as worded in the Nicene Creed). When Western crusaders sacked Constantinople, the seat of Eastern Christendom, that pretty much completed the schism.

“The ancient apostolic church that’s been handed down to the saints, unadulterated, for hundreds of years. This is how the church sees herself,” he said of ancient and modern Orthodoxy.

And, if you believe you’ve got it right, why would you change it, he explained. The Divine Liturgy, for example, has been around, virtually unchanged, for more than 1,600 years — before the church began to fracture.

Orthodoxy today is unified globally on doctrinal and authority-structure issues, Tsikouris said, but does have some regional variations. For example, all Orthodox services are mostly sung or intoned (another difference from Roman Catholicism), but Russian tradition tends to follow four-part harmony rather than the chant style preferred by other church regions.

Regional differences aside, Tsikouris said it always comes back to the actual words, the Divine Liturgy.

“Let us stand well,” he and every other practicing Orthodox priest in the world will sing on Sunday. “Let us stand in awe. Let us be attentive, that we may present the holy offering in peace.”

And the Orthodox people will sing back in their many languages: “Mercy and peace, a sacrifice of praise.” As they always have.

• Nora Edinger writes from Wheeling, W.Va., where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household. A long-time journalist, she now writes in a variety of print and e-venues, including her JOY Journal blog at noraedinger.com. Her first work of fiction, a Christian beach read called “Dune Girl,” is available on Amazon Kindle.