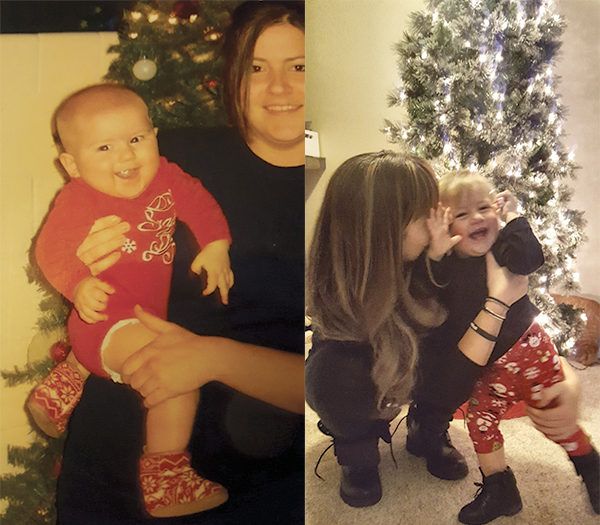

Standing in prison with her infant daughter Reagan in her arms, Kelcie Rauscher read a newspaper article about a couple who had overdosed — a few days later, their baby starved to death in her bassinet next to her dead parents.

“Right then I thought, ‘I’ll never get high again.'”

‘I’ll never get high again.'”

She’s been drug-free since Jan. 19, 2016 — that was the day she went to the Belmont County Jail, before heading to Marysville State Prison for Women to serve her sentence for drug possession.

And this year on Jan. 19, her current employer, Later Alligator, sang her praises for all the Facebook world to see, with this post:

“Today, she celebrates two years clean. Her debt to society fulfilled. She’s a brilliant Mama to the most amazing little human. She works both the front and back of the house and, without any exaggeration, is a huge part of what makes this place glow so brightly. She’s ours and we’re hers. There are not words to adequately describe how much we love her or how happy her being around makes us or how much better this business runs because of her. We couldn’t possibly be prouder of her. Happy Two Years Clean, Homegirl, here’s to 100 more. We’re with you no matter what.”

And they were.

They were with her throughout the drug years. They fired her. They hired her. They fired her again. They watched her go to prison. And they welcomed her back when she came home to Wheeling with Reagan in tow.

“It wasn’t until she came out of jail that I simply knew she had turned the corner and wanted to get clean for herself and her baby girl,” Susan Haddad, proprietor of Later Alligator, said.

When Kelcie graduated from Wheeling Park High School in 2004, she saw a typical future for herself: a good job, a husband, kids, a nice house.

Not a woman convicted of two felonies.

So How Did She Get There?

She was a heavy drinker after high school, downing a whole bottle of Captain Morgan every night. She’d carry a bottle with her when she went to the movies, to a football game.

“People made me nervous. Drinking took that away.”

A relationship with a guy who had a child changed her habit. “I couldn’t be drinking every night with a child around.”

“I didn’t like being sober,” she admitted. So the Captain stood down, replaced by pills.

“Once I started using pills, I loved it.”

She took “partying to an extreme,” she admits. And it got the best of her, literally.

After about a year, “it got really bad,” she said. “I had to have them every day. That led to coke. … It didn’t matter toward the end.” Crack, opiates, benzos (benzodiazepine, also know as tranquilizers). She never used a needle, though. She just preferred the taste as she inhaled.

After about 10 years, the only people she knew were people who did drugs. She had no friends — just “drug acquaintances.”

Throughout those years, she went to college and had a few jobs. She studied business at West Liberty University, then went to West Virginia Northern Community College’s culinary program. It was through the WVNCC program that she got an internship at Later Alligator.

All the while, drugs were taking over.

“My work ethic drastically changed. I was constantly late; everything I did in some way, shape or form was to do drugs. At lunchtime, I’d go out to get drugs. I lied all the time. I can honestly say I wasn’t a good employee.”

She realized she was “withdrawing all the time. … I knew it was a problem. You know it’s bad when you can’t get through a workday without drugs.”

She lost jobs, mainly for being late. “(One of her former employers) gave me one more chance to be on time. And I wasn’t.”

Trying to Stop

Kelcie didn’t consider herself an addict, not until the latter years, prior to prison.

“I felt like I could stop, but I didn’t want to stop.”

She tried to quit by herself, and briefly, she tried NA (Narcotics Anonymous) meetings.

A few days, a month maybe, she’d be clean. But, “I didn’t change anything else in my life. I had the same friends. No hobbies. So, I sat around by myself, alone, and go right back to it. … I hated myself.” And, when you’re sitting around feeling bad, the first instinct is to make it go away … “to get high,” she said.

“Nobody can help you if don’t want help. And I didn’t want help.”

The Turning Point

Prison saved her life.

She was charged with possession and was given the opportunity to participate in drug court, “which I failed for faking a drug test.”

Drug court, in the state of Ohio where she was charged, allows offenders to take drug tests, go to group classes, meet with a probation officer, appear in court to review progress and do community service — all instead of incarceration.

But, the moment she was seen swapping out a urine test, she was whisked off to jail. She’d been in the drug court program a little less than a year. It was Jan. 19, 2016 — the last day she did drugs.

Kelcie spent some time at the Belmont County Jail before she, three months pregnant with her daughter, was transported to the Ohio Reformatory for Women in Marysville, Ohio. Because she was pregnant, she was an inmate at the Franklin Medical Center, which is part of the state corrections system.

Reagan was born at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, and for the first seven months of her life lived with Kelcie at the reformatory in Marysville.

Marysville is one of the few prisons to have a nursery program, and Kelcie was lucky to be one of the few mothers accepted into that program. Even luckier, Kelcie worked in the nursery doing laundry.

“She was at my side almost all the time. … (that was) the only thing I cared about through all of this.”

Had she not been able to participate in the nursery program, Reagan would’ve left the prison just hours after birth. “That’s all I could think about — if they were going to take my daughter.”

Seven months after Reagan came into this world, she and her mother left the prison and moved in with her grandmother in Wheeling.

Looking Back

Ten years lost to drugs and alcohol. A lot of time wasted. Kelcie said she feels ashamed of her behavior during those years. “The lies, the manipulating, just the type of person I was. … This is something I struggle with. Those were my choices. I knew what I was doing, I knew it was wrong. But the drugs consumed me, so I didn’t care at the time.

“Prison absolutely saved my life. It sucked, and I hated it. But, I’m never going back.”

She is not angry that she spent time in prison. She said she met good people.

“I had to learn how to be a mother and to figure out who I was and learn to function, with a bunch of strangers.”

She is sad, however, she robbed Reagan’s dad and her own mother of the first seven months of the baby’s life. “They came to visit, but what’s an hour with your first grandchild?”

Incredibly Strong Support

Kelcie’s mother Nancy says her daughter is a “freaking phenomenal mom.”

“She’s had a long road, and I’m very proud of her and thankful for this little one,” she said, smiling at Reagan, who is now a typical toddler at 19 months.

“It took her (Kelcie) a long time to figure out how strong she really is.”

Kelcie and Nancy are both thankful for Susan and Mitch Haddad of Later Alligator.

“She was lucky to have people who still stood by her,” Nancy said.

Susan and Mitch hired her back as soon as she returned from prison … after being fired more than once.

“If that was me, I wouldn’t have given me the chances they gave me,” Kelcie said.

“If you made an account of every facet of this job that gives me the warm fuzzies, Kelcie Rauscher would make that list every time. Two years ago, we damn near lost this woman. High. On her way to prison. Another life destroyed by addiction. …,” said Later Aligator’s Facebook post on the second anniversary of a drug-free Kelcie.

“Kelcie’s something special. Even when she was using, you could see the brilliant bits of her doing their best to get out,” Mitch said.

Before she went to prison, Nancy, Mitch and Susan tried to sort out what was going on. “We wanted Kelcie here. We wanted her whole. Not just because she’s an ace in the kitchen, but because she’s always been special,” Mitch said.

“Kelcie’s gone from a liability to one of our best and brightest. Kelc splits her time between the kitchen and front of the house. She’s one of the strongest we have in either position. She’s reliable. … My job here focuses a lot on sustainability. How do we make sure the wheels keep turning and the lights stay on. I will prioritize the success stories like Kelcie’s over profits every time because even with the risks we take that don’t work, anyone who comes through half as strong as Kelcie makes all the work worth it.

“The Rauschers and Haddads are going to be intertwined for as long as I have anything to say in the matter.”

Words of Experience

Kelcie’s advice to drug addicts trying to get clean is “keep trying. It took me multiple times. Eventually, you’ll find the right path, and you’ll get out of it.” And for the addict who doesn’t want out: “Try not to be ashamed, not to be too hard on yourself. One day, enough is enough. One day they’ll want to stop.”

Nancy, who works in the nuclear medicine department at Wheeling Hospital, has learned a lot through Kelcie’s addiction and recovery.

“I want people to understand — don’t ever think it won’t happen to you. Have compassion for others. … Don’t judge. Be humble. Don’t look down at someone. You never know what someone else is going through.”

When she sees a person come into the emergency room, it’s not “just another drug overdose.”

“It’s somebody’s daughter, mother, son …”

Sometimes, she thinks, she doesn’t know how she made it through the last few years. “It’s a horrific thing. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy,” Nancy said.

Looking Forward

Kelcie knows she’s lucky. It could’ve been worse. She could’ve had a much longer sentence.

“People get high and rob banks and kill people,” she said.

“I could’ve died.”

“I’m not one of those people who thinks she has a purpose. But I think I’m an amazing person, a good friend, a great daughter, an amazing mom. That’s why I’m here today. That’s why I got chosen to not be dead in a gutter.”

Drugs and alcohol are an addict’s coping mechanism, she said. Now, she’s got genuine friends, a support system and a reason to live.

“For me, when I have moments I want to get high, I look back at the person I used to be, at prison, but most of all, I look at my daughter,” she said.

“I’m proud of how far I’ve come. When you’re really bad on drugs like that, you think you can’t do it. And I’m somebody who has.”

(Photos provided by Kelcie)