- (Writer’s Note: This is the first in a series of stories that will concentrate on the development and history of the New Vrindaban community in Marshall County.)

Ridiculously Different

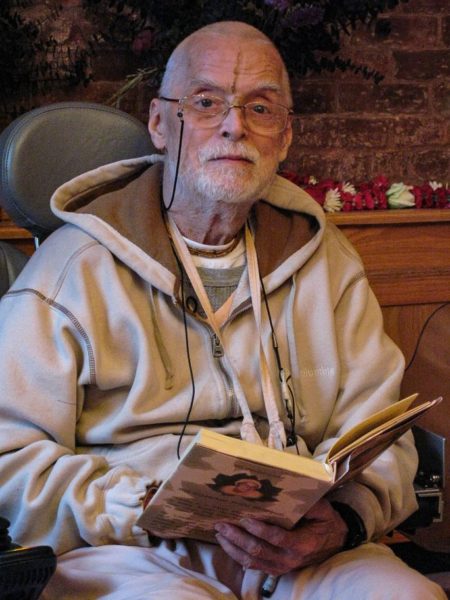

He stumbled, and he fell, but he wanted to get the story. It was up, and up some more, and then up even another hour, and Michael Gast was a muddy and bit of bloody mess when he finally found what he was looking for back in 1968.

His discovery, though, was the very, very beginning of what is now New Vrindaban and the Palace of Gold. Those robe-wearing, shaved-heads-with-a-pony-tail people encountered by Gast were in their early 20’s and hoping to acquire a marriage license so they could wed on land they considered sacred.

He was 21 years old and a third-year intern in the summer of 1968 for one of the Wheeling newspapers, and had worked his way through the obituary and police-beat duties so he could be assigned a “beat” and operate as a real reporter.

That “beat” was Marshall County, all 312 square miles of it and not only Moundsville and Glen Dale and Cameron. The county at the time was attracting new residents because of the manufacturing and industrial jobs along the shores of the Ohio River, but diverse it was not, and that is why the Hare Krishna couple attracted Gast’s attention.

“I was an intern reporter for the local newspapers in Wheeling back in 1968, but my beat was Marshall County,” Gast explained. “So, I would visit the Marshall County Courthouse pretty often, and there are a lot of different departments in that one building, so I was usually able to find something to write about. One day I walked into the Marshall County Clerk’s Office, and there were these two people wearing those robes, and they had shaved heads.

“I was trying to overhear their conversation because, well, that was my job and then finally I said to them, ‘You look pretty unusual for this area,’ and they said, ‘Oh, we know. We are Hare Krishnas,’” he said. “I knew them from the airports because they were at those kinds of places in the late 1960s, but the last place I ever thought I would see them was in Marshall County.”

But there they were, and Gast immediately became determined to reveal them to a region that was mostly Caucasian, Catholic, and cautious of everything and anyone different.

“I asked them if I could speak with them so I could do a story on them for the newspaper, and they said they loved the idea, and they invited me to follow them to where they were living at that time,” Gast recalled. “Now, they did tell me it was a four-hour hike in the woods, so I had to check at the office because I was on a deadline. The city editor at the time didn’t like me, so I doubt he cared if I got killed, but he approved it, and the Krishnas told me what to look for on the way up the hill.

“I climbed way up that hill using the landmarks, and by the time I finally found where they were it was late afternoon,” he said. “And when I did get up there, I see that they are living out of Army surplus tents, drinking fresh milk, and eating oranges. They offered me a seat on a pile of dirt, and when I looked around, I saw that some of the women were holding babies. I didn’t like that at all because of the crude conditions at their encampment.”

A Cub’s Hunger

The International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) was founded in 1968 in New York City by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, a man still worshiped by members of the movement.

So, why were these followers here in Marshall County, a place night-and-day different from the most populated city in the United States?

“That’s the story I wanted to tell, and I really wanted that story. For that part of the world to choose Marshall County? That was a big story,” Gast said. “They were like aliens from another planet. Aliens in Marshall County? Knowing the little that I knew at that time about the newspaper business, I was pretty sure that the story I wrote would be read by everyone who bought the newspaper.

“After I finally found them, I saw that it was a very rudimentary beginning and that it looked like a refugee camp. At that point, they had not even thought of building all of the temples on all of the hilltops, or having a live elephant on the property like they used to. They had been there three weeks when I visited,” he remembered. “When I asked them what they were going to do for money, they told me that they beg, and that’s what they do. When I went back after I moved home a couple of years ago, I tried to imagine where the spot was where that meeting took place, but so much has changed in the last 50 years that it was impossible.”

Gast, though, did not get to hear the story of Prabhupada’s ISKCON invention or what was planned for the Marshall County land. No one spoke of the temples, the tourism, or the temptation that would consume the community during the years to follow.

They wanted him.

“As soon as I sat down I asked them about who they are, what they are, and why they were here, and they told me that this was a sacred place and that’s why they were there,” Gast reported. “After I asked them to tell me more, they told me that they wanted me to stay. I told that I had to get back to the office, but they continued to say that they wanted me to stay forever. That’s when I got a little scared.

“I reminded them that I was a news reporter and that my bosses knew where I was, and I repeated that I had to get back, and that’s when one of them said to me that the story only becomes a story if I would become one of them,” he explained. “They were very hospitable until it all got very weird, so I told them thank you, and that’s when I went to walk away.”

It freaked him out.

One of the men grabbed his arm, twice, after he had surrendered his assignment and taken steps toward the path back because he failed to believe he possessed an aura about him as they suggested. They were Americans, and one of them, Gast believes, could have been Keith Ham, or, Swami Bhaktipada, the man who came to be the so-called spiritual leader of a village who ultimately tarnished all that gold.

“Instead of answering any of my questions, they were being aggressive with the recruiting, so I became convinced they had an idea of what they would do with me if I decided to stay. I don’t know what that may have been, but that’s what I believe,” he said. “In the years that have passed, I have done research on the Hare Krishna consciousness, and I know that it’s a religious spiritual pursuit for many, many people, but it was different in 1968. No one here was ready for that when they arrived; I know that for sure.

“I did get something when I asked why they decided to do whatever they had planned here, and they replied, ‘Why not?’ And that’s when I knew that every question I would ask would be turned into a puzzle. I told them that if they didn’t give me any more information that this wouldn’t be much of a story,” Gast said. “I kept asking for more information, and they kept saying that I needed to stay there if I wanted to learn more.”

It was the 1960s, a decade that began with a president who handled the Cold War well before he was assassinated in Dallas, and ended with the country embroiled in combat in Vietnam with thousands of draftees nearly 9,000 miles away. It was a period of time in America, Gast uttered, when no one knew what to expect next.

“It was when most people were afraid of the weird and unusual because of what they seeing on their televisions during the nightly news. And, yeah, the people I visited were beyond the standard of the unusual and weird. And they were aggressive, at least with me,” he said. “I can’t tell you how many times they told me that I was meant to stay there. I had to tell them that I was leaving more than once.

“I was polite about it, but I did have to be pretty assertive about it, and then they let me go. At least that’s how I felt at the time,” Gast continued. “I was chasing a story that I thought be a big story, and I got no story, really. It was still a big story, but it wasn’t mine.”

Beat on the Beat

It was close to hour during his hike up the hill to the Hare Krishna members when he second-guessed himself about setting off on such a journey, but on his way back down, using the same downed trees, small streams, deep hollows, rock formations, and buttocks-dragging declines, Gast felt lucky, and he felt anxious.

“There was a point in time when I did believe they were going to kidnap me because when I initially tried to leave, one of the men grabbed my arm,” Gast said. “Eventually, though, they let me go, and that’s when I set on the long walk back to a place somewhere in Moundsville.

“What I remember the most about walking out of there was that it was straight down. It was a big climb, but by the time I decided to head back down, I guess I didn’t realize just how much I did climb, and the whole time I kept thinking that as long as I was heading down, I would end up somewhere in Moundsville,” Gast said. “At least, that’s what I hoped.”

Sweaty, muddy, tired and torn, Gast finally reached his vehicle as day was fading into nighttime. He navigated the 12 miles north along WV2 back to the Wheeling office on Main Street, sat down at his desk, and tapped out what he could about his expedition to the infancy of a Krishna community that would soon attract national attention as an attraction and as an atrocity.

“I wrote the story that I had, and then I got some pretty bad news” Gast remembered. “That’s when I found out, just the day before, Susan Schubert got the story. She went there with a photographer, saw the same things I did, but had a very different conversation than what I had with the group.

“Susan and I were both students at Bethany; she worked for one paper and I worked for the other because they really competed back in those days, and her story was an excellent story. She and the photographer made that same hike, and her story had more depth than mine because they didn’t try to recruit those two,” he said. “They didn’t try to recruit Susan because, I believe, she was with a man who had like five cameras with him, so they told her that their goal was to establish a North American center for the Hare Krishna belief.”

Gast, then and now, has never assigned himself a denomination when it comes to Christianity because he doesn’t believe in beliefs, yet he has long been convinced there exists a higher power. Whether the Jews, Catholics, Episcopalians or Krishnas have religion right did not concern Gast when he set out on a journey he’d never forget.

“I thought the story would be something about something that no one in this valley would know anything about, but that they would interested in it because of how different they were from the vast majority of the people in this valley,” Gast said. “So, I am sure there would have a lot of interest in the story, and I am sure the people would want more and more information about what was going on.

“The first land purchase the Krishnas made wasn’t huge parcel, but it allowed them to start whatever it was they had planned, and since there has been a lot news about that community that we have learned because of the trials and the experiences that people have had. But I will never forget that experience meeting the very first group of people that laid claim to what it is today.”

Cops & Krishnas

Once the story was published, the Krishna community was on law enforcement’s radar, not because crimes were being committed but because no one knew what to expect. What John Gruzinksas knew when he arrived in Marshall County in 1978 to accept a position with the West Virginia State Police was that the movement’s leader, Swami Prabhupada, had passed away the year before at the age of 82, and no plan was in place for another devotee to assume the position.

“New Vrindaban was one of the first places the veterans of the State Police in Moundsville took me because they needed to get me familiar with what was going on up there,” he explained. “So, we got into the cruiser, and we went out to see the Krishnas, and at that point they only had constructed a few buildings. They had the original farm, which is still standing, and that was the place we visited first.

“It was close to lunchtime, and I saw a long line of residents that were there to get lunch, and what it reminded me of immediately was something like the photos I’d seen of a concentration camp because there were these loud speakers blaring these chants,” Gruzinksas recalled. “And, at that time, the other troopers told me that they were on a very strict diet so they would be able to do what the leaders needed them to do so the community continued to grow.”

That very first visit took place soon after the community had been quarantined because of a hepatitis outbreak, prompting officials with the Marshall County Health Department to treat several hundred residents.

“They told me that every single member of the community had to be inoculated,” Gruzinksas said. “And there were some things that took place up there that were common practice like the tremendous infant mortality rate that they had.

“They handled all of the births themselves with midwives, and I have no idea if they had any training whatsoever, but there were many times when the utility companies would be working on their land, and they would unearth caskets with children in them,” he continued. “That happened a lot because the members would bury them wherever they wanted. They weren’t marked or anything. Those children were just buried.”

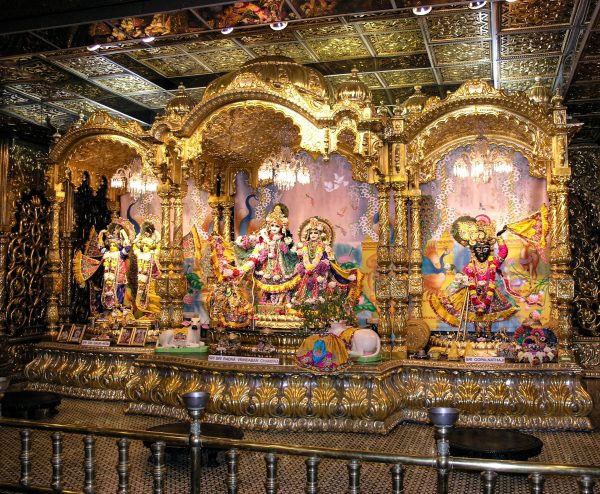

Although Gast and Schubert were not told of a Palace of Gold during their respective interviews, such a shrine was under construction and set to open to the public two years later. Built with elaborate materials from 17 countries and more than 8,000 square feet of 22 karat gold leaf trim, the palace was initially meant to serve as a residence for Swami Prabhupada. With their leader dead, though, the devotees altered the plan to involve tourism.

“The people building the palace were the residents and not employees with construction companies or anyone like that,” Gruzinksas explained. “And, when I first arrived in Moundsville, the one question no one could answer for me was where the Krishnas’ money was coming from to build such a large structure and paint it with real gold paint. No one knew much about anything even though the devotees had been on that property for a decade.

“I really didn’t believe they could finance such a project by just going to the airports and doing what they did there,” he said. “So that was a red flag for me from the very beginning.”

What Gruzinksas, who served eight years as sheriff before being elected last year to the Marshall County Commission, did figure out was how Prabhupada’s disciples were able to purchase a large parcel of land in Marshall County.

“There were only a few of them in the very beginning, and I was told that one of the first places they went was Richard Rose’s farm, and they stayed with him. Richard was a self-proclaimed philosopher, and he had self-published several books about philosophy,” the retired trooper explained. “He was one interesting cat to talk to, and he welcomed about a half dozen of the Krishnas.

“After the members traveled back and forth between New Vrindaban and their operation in New York, they brokered a deal to lease the property up there for 99 years for a token amount,” he reported. “Richard thought he knew what he was getting into, but he really didn’t, and although he argued against the deal, the Krishnas had a pretty iron-clad contract. He was stuck.”

But his wonderment about the community’s growth and revenue generation bothered Gruzinksas, and another fact with which he was concerned was that the New Vrindaban community was cared for medically by a “doctor” who was not a trained physician.

So, the trooper did what troopers do.

“During that investigation one of the people I spoke with was an official with the state’s medical association in Charleston, and when I asked what they had done to supervise the medical practice at New Vrindaban, I was told that they were just allowing them to do whatever it was they were doing back then,” Gruzinksas said. “After I asked why they were looking the other way, I was told that they did that because they did not know who else would treat the sick in that community.

“It just seemed like no one cared,” he said. “The only thing I knew about the Hare Krishnas was what I would see when I was at an airport, but what I saw during that first visit was very eye opening. It was the last thing I expected to find in Marshall County, W.Va. A huge temple in the middle of nowhere. Yup, that was a pretty big surprise.”