I am a Wheeling native.

My family, my ancestors, lie at rest three blocks from my house, up the street in Greenwood cemetery. They were a proper Victorian bunch, who began their lives just as I would do so a century later, in a pleasant valley in a pleasant town wedged between the farms of Ohio and the business of Pittsburgh. And, like them, I would find myself in an old-fashioned life, with parents and uncles and children around me, tucked neatly into a parcel of land, together.

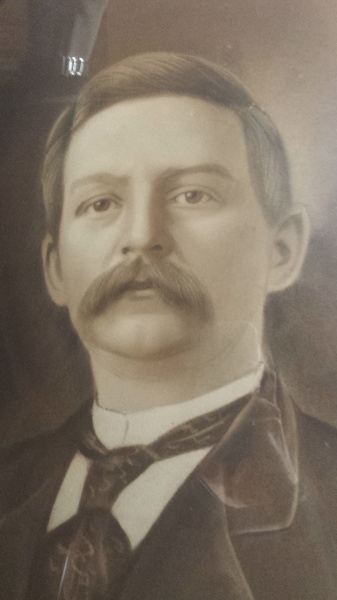

The Jeffers family were city folk as far back as I can trace them. Great-great grandfather Matthias had a knack for numbers and earned his living at several financial institutions in Wheeling. Like most upper class folk, his family lived in the city, but the very industry from which the Victorians accrued their wealth made urban life trying. Pollution was thick in the city air, and the Ohio River, which made booming industry possible, had a predictable habit of flooding. Wheeling Island and parts of downtown were frequently underwater—17 times the river flooded between 1884 and 1913.

The rural high ground in the country held understandable appeal to the elite. When the streetcar replaced the horse, the Jeffers family had every reason to abandon city life. Like many of his wealthy contemporaries, Matthias purchased a parcel of farmland which had been divided into lots. This spot was a small two acres of grass in a stunning suburb known as Pleasant Valley, so named for its quiet green hills and deep serenity. Open field sloped very gently towards a tiny run which trickled from the hillside above. In 1905, around age 60, Matthias and his wife, Mary, along with their daughter, Lottie, built a home on their Pleasant Valley parcel. But they didn’t come alone; indeed, the entire family decided that no one was leaving town unless everyone was leaving town. Thus, two of their grown children, George and Eva, settled in comfortably next door, each in their own homes of a very similar layout. They spent their lives in these three dwellings, raising children and grandchildren. In addition to my great aunts and several cousins, my grandfather grew up with his hands in this dirt and his feet in the hillside stream. Today, I live in great-Uncle George’s house.

Of the homes, it may be said that the roofs are steep, the porches wide, and the windows numerous and drafty. Stately brick chimneys adorn each sharp corner. These dwellings are not particularly temperate. In fact, they are unpleasantly still and stuffy in summer, wretchedly drafty in winter, dark on the eastern side, and inescapably sunny on the west.

The Victorians designed their public spaces to impress. The grandest spots in the home were those visible; the foyer was adorned with dark wood, intricate carvings and 12-foot ceilings. My great-greats would formally greet their visitors in the foyer and were fond of their displays of wealth. Rising up in the entering visitors’ line of sight is a massif of stairs. The woodwork is dramatic and brooding. The foyer is a sizeable room devoted entirely to receiving visitors; today, its distinctly odd shape and recesses make it a useless space for a modern family fond of overstuffed furniture and clunky pine coffee tables.

The Victorians had ways of separating themselves from the lowest common denominator. Meals were served in the formal dining room. The kitchen is accessible via three doorways, and in each hung a rather surly wooden door which prevented both residents and guests from stumbling into an area reserved for the help. To my knowledge, there was only one servant in my home at any given time. The square footage is not enormous and not what makes these dwellings imposing. Rather, it is the sheer volume of rooms and walls, nooks and stairs, baseboards and windows (36 to be precise). My grandmother used to call these houses “wife-killers” because the women of the Jeffers parcel couldn’t do it alone. The family hired housemaids, known as “half-grown girls,”and my grandfather could recall a parade of them over the years. Many were immigrants of Irish and German descent, and most would be servants for the entirety of their working years. It was a life of drudgery. A census taken in 1920 lists the names of the home’s residents, including Martha M. Tutt, age 18, “housemaid.” Martha’s daily tasks included laundry, cooking and cleaning. She found her respite in a plain little room which served as the maid’s quarters. It lurks in the recesses of the second floor, a seven-by-nine-foot chamber which abuts the attic door. Martha had a closet and one double-hung window from which pour in both blinding western sun and bitter blasts of winter draft. She enjoyed neither overhead light nor fireplace, but via the pipe on which I regularly whack my foot, she was fortunate enough to have a gas heater. If the temperature of Martha’s room in the summer of 2014 is any indication, she would have sweltered through her nights.

Martha’s route to the kitchen was a second staircase, one reserved for children and housemaids. Today, the servants’ staircase is notorious for confusing cable repairmen and deliverers of furniture, who find themselves a bit turned around. Like the foyer, a modern house would have little use for a second set of stairs which, for all intents and purposes, leads to virtually the same location as the first. And much like the foyer, the servants’ staircase is an egregious waste of space in a contemporary world, one that has no tolerance for inefficiency.

My modern life does not fit neatly into this Victorian home. What I have found, though, is comfort, and appreciation for ancestry and for family. Still, it is an effort to fit a square peg into a round hole; we tinker with the house until it fits our needs, and the final result is a satisfying amalgam, a designer dog who isn’t quite Labrador and isn’t quite Poodle. The junction bridges the gap as best it can. And so we run our high speed internet cables under the hardwood floors, and construct our Ikea shelving in the closets where Mary’s long skirts once hung. The house, if it is to survive our tenure, needs to keep up with the new Jeffers. We want to live here, but we aren’t willing throwbacks. The house has accepted our changes graciously, and we have been respectful. The stone around us is our foundation, but the value lies in the life we’ve built.

There are those who would say we can restore these old homes, bring them back to dignity, or tear them down and make way for the new. A preservationist will work hard to recreate the past, to encapsulate the feel of a morning in the parlor or an afternoon on the porch. A developer will fit the land to new and profitable purposes. But for those who dwell here, who rise and make coffee and plant zucchini and check email, there is no choice, and we cannot commit to either fate. The house must serve as ever so much more than a roof over our heads. It becomes a reference book, a genealogy chart, and a blank canvas on which future generations will write their stories. Rather than an elite statement of stature, the Victorian skin must change its color and become something a little less defined. It’s a lot to ask of a house, to be something it wasn’t born to be, to straddle one-hundred twenty years of tradition and progress, formal art and winsome comfort. Matthias couldn’t have envisioned his descendants’ purpose in Pleasant Valley, but the little biome he created has sustained his legacy with surprising adaptability.

My family is here, still, in a rare alignment. My parents live next door to me, and for a time my uncle was in the third house. History, as it is wont to do, repeated itself. It’s said often that Americans need to get back to the family community, but this is a difficult endeavor and must fall into a “perfect storm” category, whereby ages, incomes, employment and health all line up to form a lucky portal into an elusive harmony. And, were we all to move in next door to our parents and siblings, how many of us would really find such a fabled land of camaraderie, free of judgment and guilt?

Not many, I’d wager. My family seems to survive each other with a modicum of grace, but perhaps we’re still too Victorian to be anything but polite. We don’t throw elbows or accusations, and we stuff our complaints into a tight little out-of-the-way compartment, because our heritage reminds us that we are still on display, and the public spaces are for viewing.

I’m compelled to ask the house, in quiet moments, if the old family unraveled when the parlor doors closed. Did they erupt into working-class discourse, or were the Victorian values in their very marrow? Did the family which greeted visitors in the foyer maintain their propriety on the second floor, in private spaces?