It was created in 1957 by the members of Wheeling City Council, and it was known as the Urban Renewal Authority. It was funded by the federal government via the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the adopted projects cleared more than 300 residential and commercial structures from the Friendly City’s landscape in less than 20 years.

The URA would submit plans to HUD officials once a specific project for a small area was selected, and once the funds were granted, the defined steps would be completed in stages. The first Wheeling-based project took place between 1970-71 in the Center Wheeling section and involved a two-block area along Main and Chapline streets and from 24th to 26th Street.

The U.S. Post Office, constructed complete with the city’s primary distribution center, was relocated to the area along Chapline Street, and an light-industrial shipping dock, large enough to accommodate more than 15 semi-tractor trailers at once, was built along Main Street.

The project erased 195 residential properties in Center Wheeling.

The URA’s second adopted project once again attacked a residential neighborhood in Center Wheeling. A total of 42 homes were purchased and demolished, and constructed on the land was an medical education and administration building as well as a structure to house a comprehensive mental health facility.

“And then they progressively got more ambitious,” said Wayne Barte, a former city manager of Wheeling who began his municipal government career in 1972 as an assistant in the city’s development office. “The next project was called the ‘Neighborhood Development Project,’ and it involved making land available for the construction of homes at that time. It was east of Chapline Street in the East Wheeling area around the top of 13th Street.

“That program involved grants and 3 percent loans, and architectural advice,” he continued. “That project was met by moderate success just like the others.”

The door knockers delivering eminent-domain messages were quite common in the Wheeling area between the mid-1950s through the 1970s, and along with the erasing of the Center Wheeling neighborhoods, the Elm Grove, East Wheeling, and South Wheeling areas lost hundreds of homes.

“Those projects were taking place during the same time we saw the interstates take many homes, and so did the construction of W.Va. Route 2 in several areas,” Barte said. “So all of these projects, put together, probably had something to do with the population decline in the city of Wheeling.

“While a lot of those people didn’t necessarily move away from the area, many of them moved out of Wheeling, and we saw communities like Bethlehem, Mozart, and Mount Olivet start to development with a lot of residential homes. Many of those folks moved up on those hillsides,” he continued. “When I was growing up in Bethlehem, I remember Mount Olivet being nothing but farm after farm, but now you see a lot of homes in that area, and all the demolitions that have taken place is the reason why.”

Homes vs. Bulldozers

There is no telling what history and architecture were erased, but the good news is that Sean Duffy and staff members at the Ohio County Library have been collecting and archiving much history about Wheeling’s storied past. Many of those tales can be discovered by visiting Archiving Wheeling.

“I doubt government would be able to do what they orchestrated back then these days because it would not be acceptable, and it wouldn’t be tolerated today,” Barte said. “We have seen the reactions to similar projects in Center Wheeling for the Lowe’s development and in East Wheeling for the all-purpose ballfield. People have very strong feelings now about home ownership, property rights, and history, so anything like an Urban Renewal Authority and projects like these would be pretty hard to deal with now.

“Think about if someone came to you at your house today and said they were going to take your house and give you fair market value, whatever that might have been, and that they were going to pay some of your relocation costs. Think about how you would react to that today,” he continued. “These days when something similar takes place, we’re talking about vacant, abandoned properties like many of them were in East Wheeling, but then it involved knocking on doors and telling people to get out of their homes.”

Although it does not seem too long ago, a different attitude about history was employed by both private residents and civic leaders in middle years of the 20th Century. Any building considered “historical” couldn’t possibly be present in Wheeling, many at the time believed, despite the city’s recorded history concerning the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the creation of the state of West Virginia in 1863.

Here in Wheeling, old was just old back then, and that is likely why Independence Hall was once a dilapidated building that housed an insurance agency and a tropical-theme bar until former W.Va. Gov. Arch Moore identified it as historical in 1980.

“The character and the architecture of a home and of neighborhoods were not things that we took into an account back then, and it was the same way nationally,” Barte recalled. “There were a few places where preservation was important, like Washington, D.C. , Williamsburg, and Philadelphia, but when it came to projects like these the people picked out areas that were just considered old and not historic. There was a difference in the interpretation at that time.

“Now we work hard to preserve structures because of the architecture character, and the ones that fit with the character of the overall community,” he said. “But here, it was the Friends of Wheeling who were the first ones I recall identifying those types of structures. But I can tell you that Wheeling was not different from most cities around the country and Urban Renewal was really a federal effort to boost economies across the United States.”

A New Fort Henry?

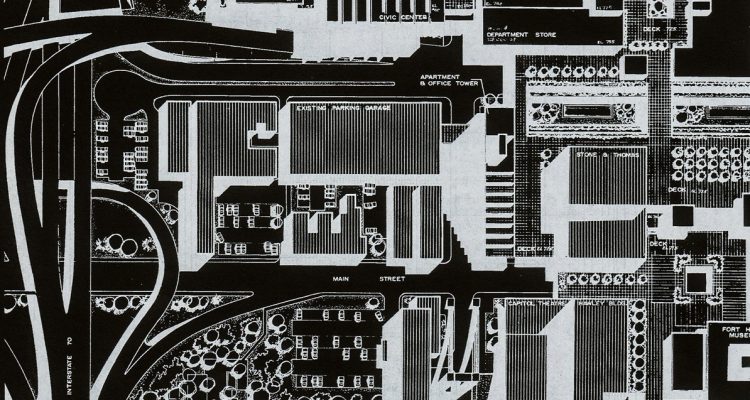

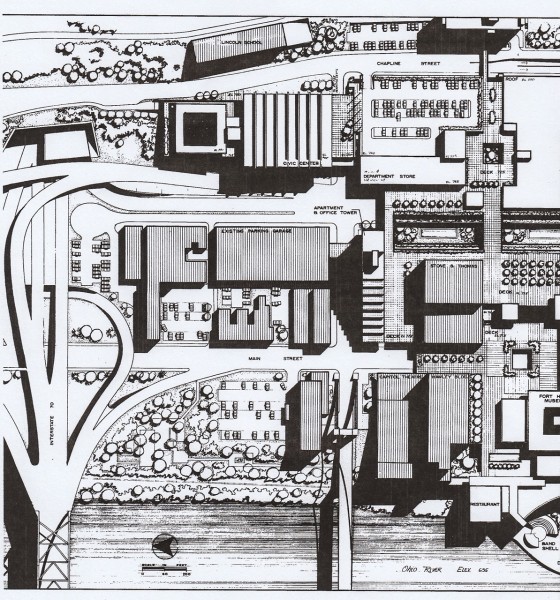

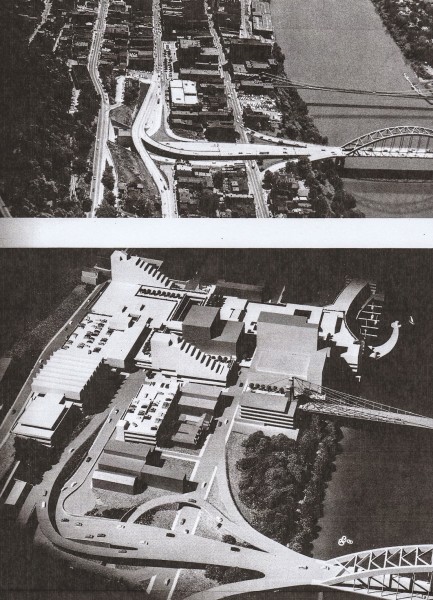

The same mindset was present, according to the Urban Renewal Annual Report from 1970, when the Central Business District Project was the next difference-making, wrecking-ball-related, “revitalization” project that involved a downtown mall concept complete with a civic center near Wheeling Tunnel and not along the Ohio River at 14th and Water streets.

“The anchor, in the beginning, was the construction of a civic center, and initially the location for the civic center is where the Montani Tower now is located,” Barte reported. “But the projections for the civic center came in way over budget, and they knew then that they would have to select a different site for that facility.

“The project then grew into what we know now as the Fort Henry Mall project, and the goal was to have 550,000 square feet of retail space by the year 1980, and the goal was from 1970 to 1990 to increase that amount of space to 770,500 square feet, and then to 1.6 million,” he recalled. “It was a multi-level concept that would have pedestrian walkways and a civic center that would have 6,500 seats. It would also have included a parking facility large enough for 2,500 cars.

“The original project was initially scheduled to begin in 1972 with the civic center and the parking structure, but they would have had to declare the downtown a blighted area, and that probably was the beginning of the downward spiral of the project. When you had, at that time, a busy downtown with a lot of businesses that were successful and you had to declare that 90 percent of it was a slum-and-blighted area, it was not the best public relations move.”

The publicized intent, though, was to further strengthen Wheeling as the commercial center of northern West Virginia, eastern Ohio, and western Pennsylvania by revitalizing a prime portion of the city to realize the downtown’s full potential. Along with the civic center and an expansion of retail space, there would have been a pair of high-rise apartment towers, a Fort Henry Museum, a riverfront restaurant and other new eateries, a harbor facility for pleasure craft, and a parking garage that could have fit as many as 2,500 cars when all was said, taken, and done.

The plan also called for additional square footage with a goal of reach as many as 1.6 million square feet through property acquisitions that were scheduled to continue through 1990, and that was supposed to increase the amount of employment opportunities in Wheeling and the surrounding areas. The mall was to slope from Chapline Street to the riverfront, providing natural street access on several levels.

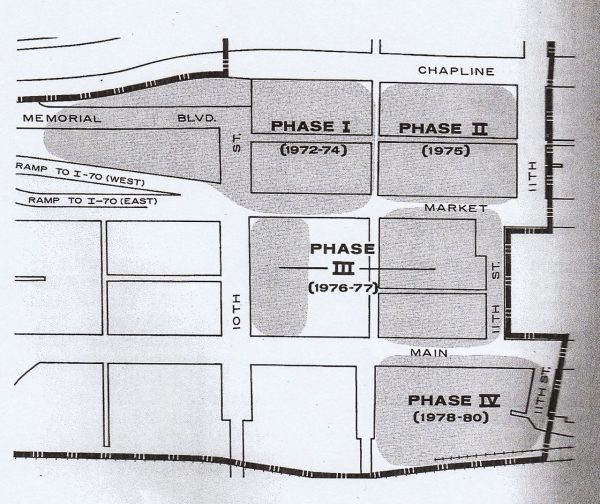

The civic center was initially planned for an area between Chapline and Market streets and between 10th Street and the entrance to Wheeling Tunnel. Main Street was to continue to be open to one-way south traffic, and Market Street would have remained one-way to the north, but traffic patterns on Chapline and 11th streets would have been altered to make way for the Fort Henry Mall.

Oh yes, and there would be one giant roof over it all.

“Yes, for the lack of a better term, the Fort Henry Mall project involved covering over the downtown with a roof, and while the existing buildings would have remained, there would have been some new buildings, too,” Barte said. “The designs for the exterior were what were considered then as ‘modern’ and we’ve seen the same concept with the Wesbanco’s headquarters and the Boury Center (now Century Plaza) buildings. That was modern then.

There would have been enclosed pedestrian walkways that would have linked all of the stores between Main and Chapline streets, and some areas would have been open-air. The shopper, according the project plan, still would have the opportunity to shop in air-conditioned areas during the summer and heated areas during the winter months. The complete mall complex would have encompassed the blocks between 10th and 12th streets and from Chapline to Water streets and would have been constructed in several areas over a five-to-seven year period.

Until the people were heard, that is.

Under a Monster’s Attack

The first stage was initially scheduled to begin in 1972 and was to include the construction of the civic center, structures for a new department store and specialty shops, a pedestrian plaza, and a 400-car parking garage. The second stage was set to begin in 1975 and would have been dominated by the building of an apartment and office tower, and the third stage, between Main and Market streets, was set to start in late -1976 and would have provided an expansion of available retail space.

And then the fourth and final stage in the development of the Fort Henry Mall, scheduled for a two-year phase (1978-1980), would have included a new marina, a riverfront restaurant, the museum near the original site of Fort Henry (constructed in 1777), and a plethora of pedestrian areas.

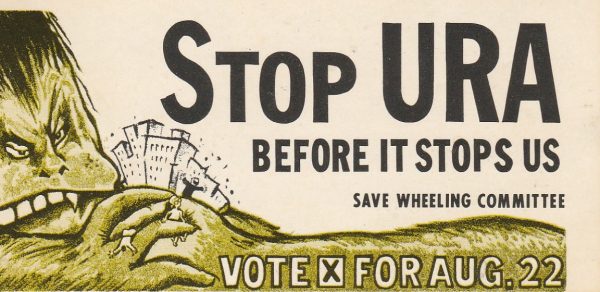

But that is when business owners and prominent citizens partnered to oppose the Fort Henry Mall, and their efforts ultimately proved most successful. The group distributed propaganda which featured a sketch of a King Kong-like character with a two-pawed strangle-hold on the Friendly City’s downtown district.

“The businesses that were open within the designated area would have remained because why would anyone want to get rid of a successful business? Think about it. Why would you bring in a business like Kay Jewelers when you already had jewelry stores that had served people in this city for years? That part made sense,” Barte said. “But, as far as the other businesses that might have come into town, well, I wasn’t a part of those conversations. Those decisions were up to the people at the Urban Renewal Authority and the experienced developer they never really got to hire.”

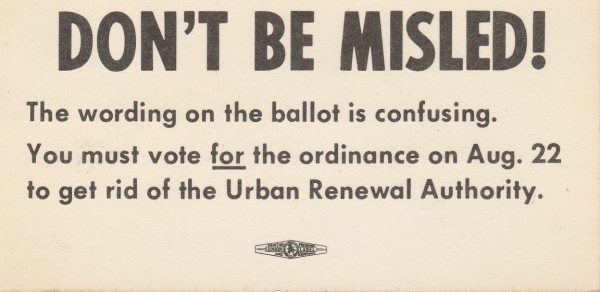

That’s when the beast of opposition appeared in 1972. The “Save Wheeling Committee” launched an aggressive campaign after court orders mandated a public referendum on the project’s continuance and the existence of Wheeling’s Urban Renewal Authority.

“Those business owners had a vested interest in the central business district and they didn’t believe the Fort Henry Mall plan was the best way to proceed,” Barte said. “They went through different legal maneuvers and they were successful in getting the issue on the ballot on Aug. 22, 1973, as a referendum issue. And they won overwhelmingly.

“The vote was 8,421 to 4,021, and that’s a butt-whooping no matter how you want to look at it. Those voting results are what instructed city council to repeal the 1957 ordinance that created the Urban Renewal Authority, and all the city was permitted to do was finish up on the projects that were already in motion, and that was it. The legal case continued to federal court, but it changed nothing. We just had to close it up, and that’s where I became involved.”

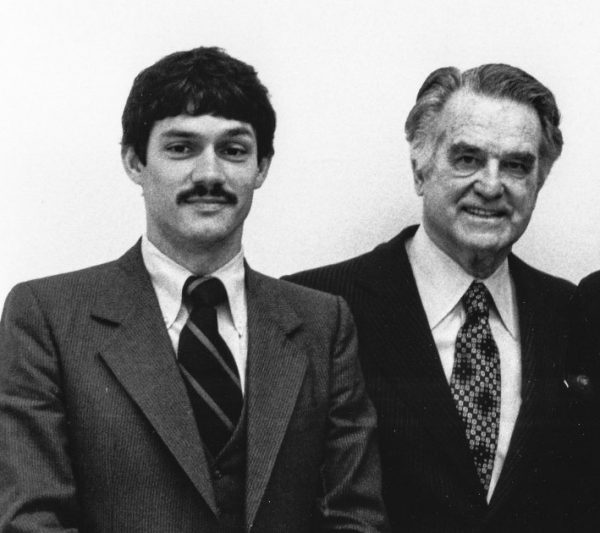

Barte climbed the municipal ladder to assistant city manager in 1976, and then was hired as Wheeling’s city manager in 1979. He stayed in the position until taking a position with TCI, Inc. He recalls, though, that before the decisive vote there were floating rumors about a different mall project near St. Clairsville. And he recognizes the same confusion still exists today as far as why the project died and whether or not the Ohio Valley Mall in Belmont County was the result.

“But, see, the Ohio Valley Mall was truly a completely different project, and the Caffaro Company had nothing to do with the Fort Henry Mall concept,” Barte said. “The Ohio Valley Mall project was going to happen regardless of the Fort Henry Mall project.

“The people who were members of the ‘Save Wheeling Committee’ represented very successful businesses and long-term businesses, and they were a force to be reckoned with,” he continued. “And then, ironically, many of those business owners ended up moving their stores to the Ohio Valley Mall because, at that time, it was the best business decision to make. They all wanted to preserve their market share in the downtown and at the mall.”

One retailer who remains in business is Howard Posin, owner of Howard’s Diamond Center at The Highlands. Posin remained in business in Wheeling’s downtown district until 2010, and is now located near Marquee Cinemas and West Liberty University’s facility. Posin sold his building in downtown Wheeling to the city in 2014 for $58,000.

“All Urban Renewal wanted to do at that time was buy the properties and tear everything down,” he recalled. “And I thought then that the developer that was involved was pretty shaky, so I joined the opposition against the mall plan. Plus, we found out that J.C. Penney and Sears both agreed to relocate to the Ohio Valley Mall once it was going to open.

“There was a time when you could get anything you needed in downtown Wheeling, and we were just trying to maintain that as long as we could, but if we were still in downtown today, it would be a sorry affair,” he continued. “Retail these days takes place at the Ohio Valley Mall, at the (Ohio Valley) Plaza on the other side of the interstate, and here at The Highlands. It’s a trend that started more than 40 years ago, and it continues today, but the mall plan for downtown Wheeling would have certainly failed because at the time of the vote no real deals were in place. We opposed what we had to oppose.”

What’s the Draw?

These days downtown Wheeling businesses are barred from purchasing advertisements on signage managed by the state’s “Attraction” sign program because of traffic patterns, and the majority of economic development that has taken place in Ohio County over the past 15 years has occurred at The Highlands near Dallas Pike.

Would the Fort Henry Mall have made a difference, in the 1970s and even today?

Would the downtown’s 1100 block still consist the buildings where L.S. Good, National Record Mart, G.C. Murphy’s, Jupiter, Rite Aid, River City Dance Works, and Feet First were located?

Or would it have turned out like a similar project in a very similar-to-Wheeling city in western Ohio – Middletown – located north of Cincinnati?

The “City Centre Mall” was constructed within Middletown’s downtown district in the early 1970s, and was demolished by the 1990s. Barte, as a representative for the cable company, traveled there and noted the failure. Middletown was a steel town, too, and the middle-class demographics were very close to those in Wheeling at the time.

“No one was fooling anyone,” Barte said. “You could go to a mall that was really a mall and everyone knew those complexes were much different than a downtown with a roof over it. Eventually, in Middletown, they tore it all down because the concept just didn’t work.”

But in Wheeling?

“Sitting here in 2016, I have to wonder if it would have been successful because the complex would have had to go up against a brand new mall that opened in 1977,” Barte said. “Knowing that, I really would have to say that no, the Fort Henry Mall would not have been successful. It was a doomed effort, really, if you think about it. It just was doomed from the beginning.”

(Photos by Steve Novotney, images from the Fort Henry Mall report, 1970)