My Grandma, Lizzie, who had been blind since she was a little girl, patiently endured the barrage of sitcoms, detective dramas and westerns. One of us took up the assignment of telling her about the nonverbal action that she couldn’t see. That meant describing how Red Skelton transformed himself into a seagull to tell Gertrude and Hecliff jokes or how Dick Van Dyke tripped over that footstool every week.

All through our hours of family television consumption, Grandma rocked in her big, puffy, gold rocking chair. The vigorousness of her rocking corresponded to her level of involvement in the show. A light rock meant she was concentrating more on the sewing or crocheting that she pursued while listening. A robust quick rock indicated that she was deeply invested in the story that was unfolding. Her complete disinterest was signaled by a sudden need to take care of something in the kitchen.

One night, after a particularly stupid episode of the Beverly Hillbillies that required me to describe for Grandma how Granny chased Jethro around the cement pond, my mother, Mabel, had enough and suggested something radical. She suggested that we read a book!

Part of it was a desire to raise our intellectual standards, but I figured out years later that the suggestion was also her attempt to scratch a long-germinating itch to perform.

Back around 1930, when Mabel was a student at Ritchie School in Wheeling, her blind parents managed to save up enough money to bestow upon her the gift of a year’s worth of what she always called elocution lessons — the study and practice of speaking or reading aloud including the control of both voice and gesture.

As a young widow in 1963 with responsibility for two young sons and an aging blind mother, she hadn’t had very many opportunities to practice her childhood hobby over the previous 30 years. Now, she had a captive audience, and she wanted back in action.

“How exactly would that work?” Terry the teenager asked in a way that indicated he wasn’t quite on board yet.

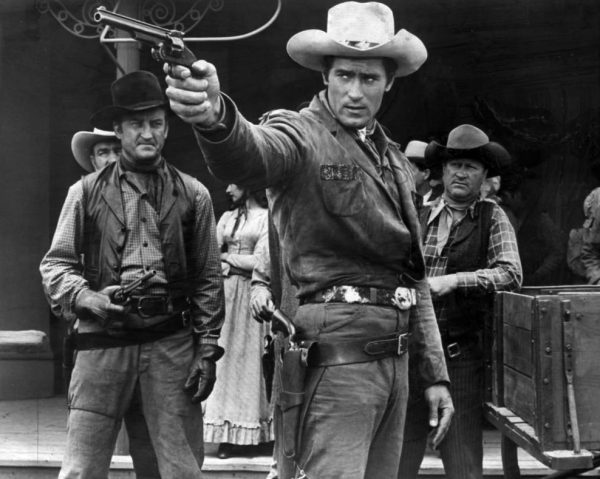

“We can still watch Cheyenne, right?” I asked, betraying a 9-year-old’s priorities.

“Well, I could read it out loud,” my mother replied. “It would be more entertaining and easier for Grandma to follow than having us describe what’s going on in a TV show. To be honest, I don’t think I have it in me to describe for her again how Hazel tricked Mr. B into doing what she wanted. Besides, you boys could get more time to play chess while you listened. And yes, there would still be plenty of time for you to watch your programs.”

Terry, a freshly minted member of the Triadelphia High School chess club, had taken it upon himself to teach me how to play chess with disappointing results for me but a string of unheroic victories for him. But, I continued to learn and try to score a win. Yes, we could play and listen at the same time.

“I know just the book to get us started,” my mother said, arising from her living room chair and heading for the basement where there was a wall of rickety wood shelving that housed jars of applesauce that Grandma “put up” in Mason jars last season, cans of Chinese bean sprouts (someone once told my Mother that bean sprouts were a miracle cure for burns), unused flower vases and a small aging collection of dusty books that belonged to my father and sat untouched for a decade.

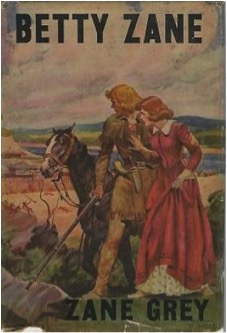

When she re-emerged from the basement, she cradled a small hardback brown book. Its dust jacket had been lost long ago, and the front and back cover was covered with nothing but the initials “ZG” in a repetitive design. Not until she turned it sideways could the writing on the spine be deciphered. Terry squinted to make it out.

When she re-emerged from the basement, she cradled a small hardback brown book. Its dust jacket had been lost long ago, and the front and back cover was covered with nothing but the initials “ZG” in a repetitive design. Not until she turned it sideways could the writing on the spine be deciphered. Terry squinted to make it out.

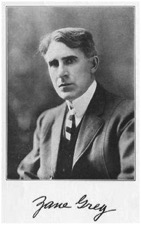

“Betty Zane by Zane Grey,” he said. “Wasn’t there a show called Zane Grey Theater on TV a couple years ago? Isn’t Betty Zane the one who was chased by Indians and jumped off of Wheeling Hill?”

“No,” responded Grandma taking a break from sewing a button on one of my shirts. “You are thinking of McColloch’s leap. Betty Zane was the girl who took gunpowder in her apron into Fort Henry when they were being attacked by Indians.”

Grandma knew her Wheeling history.

My Mother explained that Zane Grey was a writer of western tales who was a descendent of the Zane family that founded Wheeling.

There was consensus to proceed.

“But let’s get started,” I cautioned. “The Rifleman comes on at 8:30 and, this week, he has to defend the town against outlaws while Sheriff Mica is out of town all while helping Mark take care of the ranch.”

For the next two weeks, we spent an hour every evening listing to my mother read the words Zane Grey used to describe how Louis Wetzel exercised his unique set of skills to foil the turkey-calling Indian who lured hunters to their deaths from the concealment of a natural cave; how Wheeling’s Fort Henry survived a siege by 300 Wyandot, Shawnee, Seneca and Delaware Indians and 50 British Rangers in 1782; how brave Betty Zane saved the day by dodging mini balls while running for gunpowder between a blockhouse and the fort; and how Betty fell in love with a lanky frontiersman named Alfred Clark.

For the next two weeks, we spent an hour every evening listing to my mother read the words Zane Grey used to describe how Louis Wetzel exercised his unique set of skills to foil the turkey-calling Indian who lured hunters to their deaths from the concealment of a natural cave; how Wheeling’s Fort Henry survived a siege by 300 Wyandot, Shawnee, Seneca and Delaware Indians and 50 British Rangers in 1782; how brave Betty Zane saved the day by dodging mini balls while running for gunpowder between a blockhouse and the fort; and how Betty fell in love with a lanky frontiersman named Alfred Clark.

We all agreed that the experiment was a resounding success that we should duplicate with another book when we could.

But, Terry was an active teenager with a growing interest in music. I became a Cub Scout. There were brooms and mops for us to deliver for my Grandma’s little telemarketing business. There were friends to visit and church events to attend. We never got around to a second book. (Click on the links for related Griffith Files tales.)

However, the experience kindled a love of Wheeling’s early history and a devotion to books that continue to this day. There has never been a time in my life when I wasn’t reading one or more books. I have my mother, her elocution lessons, Zane Grey and the absolute stupidity of some of those 1963 TV shows to thank for a lifetime of reading entertainment.

For an excellent story about the 1782 siege of Fort Henry, check out a Weelunk story here.

• Gerry Griffith was born and raised in Wheeling’s Elm Grove section. He pursued a career in journalism before working on Capitol Hill for then-Congressman Alan Mollohan in Washington, D.C. He returned to Wheeling and stayed nearly 20 years to work at Wheeling Jesuit University, Touchstone Research Laboratory and in Congressman Mollohan’s Ohio County office. He also worked for the West Virginia University Research Corporation. He currently lives near Pittsburgh where he works at the National Energy Research Laboratory. He is also a contributing editor to a national industrial research publication and dabbles in fiction writing.