There are many different ways to find windows to the past. Some take advantage of the genealogical resources in the Wheeling Room at the Ohio County Public Library, others may just sit by the river and imagine what it was like when it was a major shipping thoroughfare. One of the more unique ways to gain insight into the daily lives of the Wheelingites of days gone by is by examining their possessions…specifically their trash. Taking a look at what was thrown out, and by whom can reveal information about socioeconomic status, personal habits, and hygiene practices of residents. Sure, taking a shovel to any yard in the city may reveal broken plates, glass, or rusted metal, but there’s a less obvious place to look: in historic privy pits.

Before the arrival of indoor flush toilets in Wheeling, there were privies. Pits were dug and lined with brick or stone and enclosed in small buildings. When nature called, members of the household would have to trek out to the privy, or outhouse. Beyond their intended use, these pits would often serve as a place to throw household refuse.

The meaning of trash changes

In the 19th and early 20th century Wheeling, trash collection was a patchwork of providers who, if hired, would load their wagons with bones and other food scraps to be taken away. 1

At this time, the term “garbage” referred to only organic waste (things that could decompose) and did not include hard goods like bottles, crockery, dishware, and so on. Sensibilities around possessions were different at this time– single-use objects were rare and when something broke, all attempts were made to mend it for continued use. Clothing was patched, rags were sold to rag-collectors,2 broken china was boiled in milk, 3 and glass bottles could be refilled infinitely.

When items were considered broken beyond repair, they would have to be discarded. And because the disposal of items was a problem for individual households, things would often end up in the immediate vicinity of the home: in trash pits, in piles, or sometimes down the privy pit. As such, privy pits became treasure troves for archaeologists, and anyone else curious about past trash.

Why here, why now?

In the early 2000s when the Post Office on Chapline Street (also called Federal Building) was set to expand, an archaeological excavation took place.4 During the survey, they identified five privies. These privies were associated with seven middle-class families, their borders, and their domestic help. The dates of occupation associated with these features spanned nearly 100 years, from 1844 to 1938.5

Archaeologists excavated these privy shafts, took detailed notes, made drawings, and dutifully cleaned the recovered artifacts. They compiled their findings in a report, which is housed alongside the collection at the Grave Creek Mound Archaeological Complex in Moundsville, West Virginia. Some items are on display in the museum, while others haven’t been examined since they were first put into boxes back in the early 2000s.

Let’s take at just a few of the items in this collection:

Ceramic Pot

Beyond fine glass and china, few decorative items were recovered from the privies on Chapline street. In this image a ceramic hedgehog crocus pot and an elephant wall sconce are shown. Wedgwood was known for making hedgehog crocus pots 6, but it is unclear if this a true Wedgwood or just an artful imitation.

Boots

Boots don’t fit anymore? Can’t find someone else who can wear them? Soles beyond repair? Down the privy!

Knit Hat

This is a knit hat with a soft brim, which is why it’s flared on the right side. Items such as this, that appear to have been in good repair may have fallen in by accident.

Spoon

This is another probable accident. Since privies were repositories for kitchen scraps, it’s possible that someone lost their grip on the spoon while they were using it to brush scraps into the privy.

Seasoning Shakers

Three different shakers were found without their pair. Aside from the caps, they are mostly intact. Why they ended up down the privy is a mystery.

Bottles…Lots of Bottles

The McLain Brothers operated assorted drug stores, medical supply depots, and provided a penny post service in Victorian Wheeling. They opened their first store in 1859 at 38th and Jacob Streets. 7

Syrup of Figs didn’t get its start in Wheeling, but it was absorbed by the Neuralgyline Company (later known as Sterling Drug) in 1912 and was subsequently made in the city. 8

These tiny bottles were issued by Dr. J.W. Morris, one of the handful of Homeopathic doctors in Victorian Wheeling.9 Homeopathy is a system of alternative medicine with ultra-diluted preparations. The understanding is that the further an item is diluted, the more potent it is. That might explain why these bottles are so tiny.

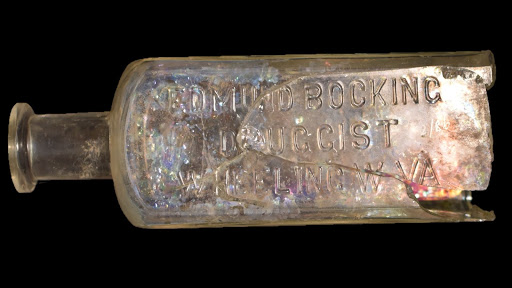

Edmund Bocking was a prominent and experienced druggist who brought about pharmaceutical reform in West Virginia. The new “Pharmacy Law” of 1882 regulated the sale of intoxicating liquors, poisons, and in what situations they could be prescribed.10 Bocking founded the State Pharmaceutical Association and was the commissioner of the Pharmacy of West Virginia for four years. 11

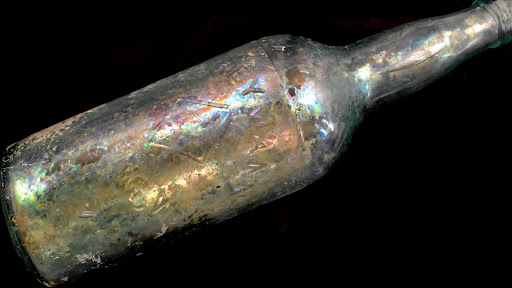

It might be a bit hard to make out, but this is a Reymann beer bottle! One of the giants of beer brewing in Wheeling, the Reymann Brewing Company was the oldest in Wheeling. The brewery’s size and success, coupled with their popular beer garden at Wheeling Park (which Anton Reymann bought), inspired a healthy rivalry with Henry Schmulbach. 12

Henry Schmulbach was an eccentric, yet successful Beer entrepreneur in Victorian Wheeling. He purchased the Nail City Brewery in 1882 and renamed it after himself, and increased production to 200,000 barrels annually. 13 His rivalry with Anton Reymann led him to create his own beer garden, Mozart Park.

Listen – Henry: The Life and Legacy of Wheeling’s Most Notorious Brewer

If these Stratford Springs look a bit more modern than the other artifacts in this article, you’re right! These were recovered from the same area, but not in one of the privy pits.

What Trash Can Tell Us

Sifting through someone’s trash can be a touchy subject. Even though trash consists of discarded items, they can and often do maintain a relationship with its previous owner. For example, these items recovered aren’t just viewed in a vacuum. We can look at what was thrown away as a “sample” of household possessions. For each broken cup thrown down the privy, we can guess that the household owned more of the same kind. Medicine bottles imply that someone was treating an illness, kitchen scraps like bones and fruit pits can provide insight into what was on the table. In one privy, the archaeologists found corroded pieces of a trumpet. While odd, it makes a bit more sense when we learn that the person associated with that privy was a music teacher.

A trumpet with assorted writing utensils and other items recovered from a privy.

Thankfully, Wheeling residents no longer have to use privies or find creative ways to dispose of their broken crockery (see: burying in the backyard). Instead, there is municipal trash pickup, private recycling services where the items are taken “away.” Where is away? That’s a story for another day, but rest assured that researchers have their eyes fixed on the next trash frontier: excavating landfills.14

This work was produced as a result of an AmeriCorps Civic Service Project at the Grave Creek Mound Archaeological Complex in Moundsville, West Virginia. This project entailed digitizing materials associated with the Wheeling Federal Building Collection, photographing artifacts, and producing new interpretive materials.

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.

References

1 Report of the Health Department of the City of Wheeling, West Virginia. 1913. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/document_center_uploads/9d_1913_Whg-Health-Dept-Report.pdf

2 Susan Strasser. Waste and Want: Towards a History of Trash. (New York, N.Y., Henry Holt and Co. 2000) pg. 13

3 Ibid, pg. 25

4 National Park Service, Archeology Program. Archeology and Historic Preservation Act (AHPA). https://www.nps.gov/archeology/tools/laws/ahpa.htm

Per the Archeological and Historic preservation act of 1974, Federal agencies are required to conduct surveys and record data that may be lost or destroyed due to construction activity.

5 John Milner and Associates, Rebecca Yamin, PhD (editor). Middle-Class Life in VIctorian Wheeling: Phase IB/II and III Archaeological Investigations 2003

6 World of Wedgwood – Wedgwood and Nature: Hedgehog Bulb Pot and Stand. http://hieronymusobjects.com/hedgehog-in-black-basalt-wedgwood

7 Gibson Lamb Cramner, History of Wheeling City and Ohio County, West Virginia and Representative citizens. 1902. pg 815

8 Ohio County Public Library. “Sterling Products Co.” https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/sterling-products-co.-sterling-drug/7140

9 J.W. Morris, 1882 Wheeling, West Virginia City Directory.

10 Wheeling Daily Register, July 25, 1882

11 Brant & Fuller, History of the Upper Ohio Valley. Vol. I, Page 225. https://www.wvgenweb.org/ohio/biobock.txt

12 Logan Bell. “Reymann Brewing Company.” Clio: Your Guide to History. May 3, 2017. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.theclio.com/entry/39323

13 Ohio County Public Library. Biography: Henry Schmulbach. https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/research/wheeling-history/5835

14 Colleen P. Popson, Museums: The Truth is in Our Trash. 2002 https://archive.archaeology.org/0201/reviews/trash.html