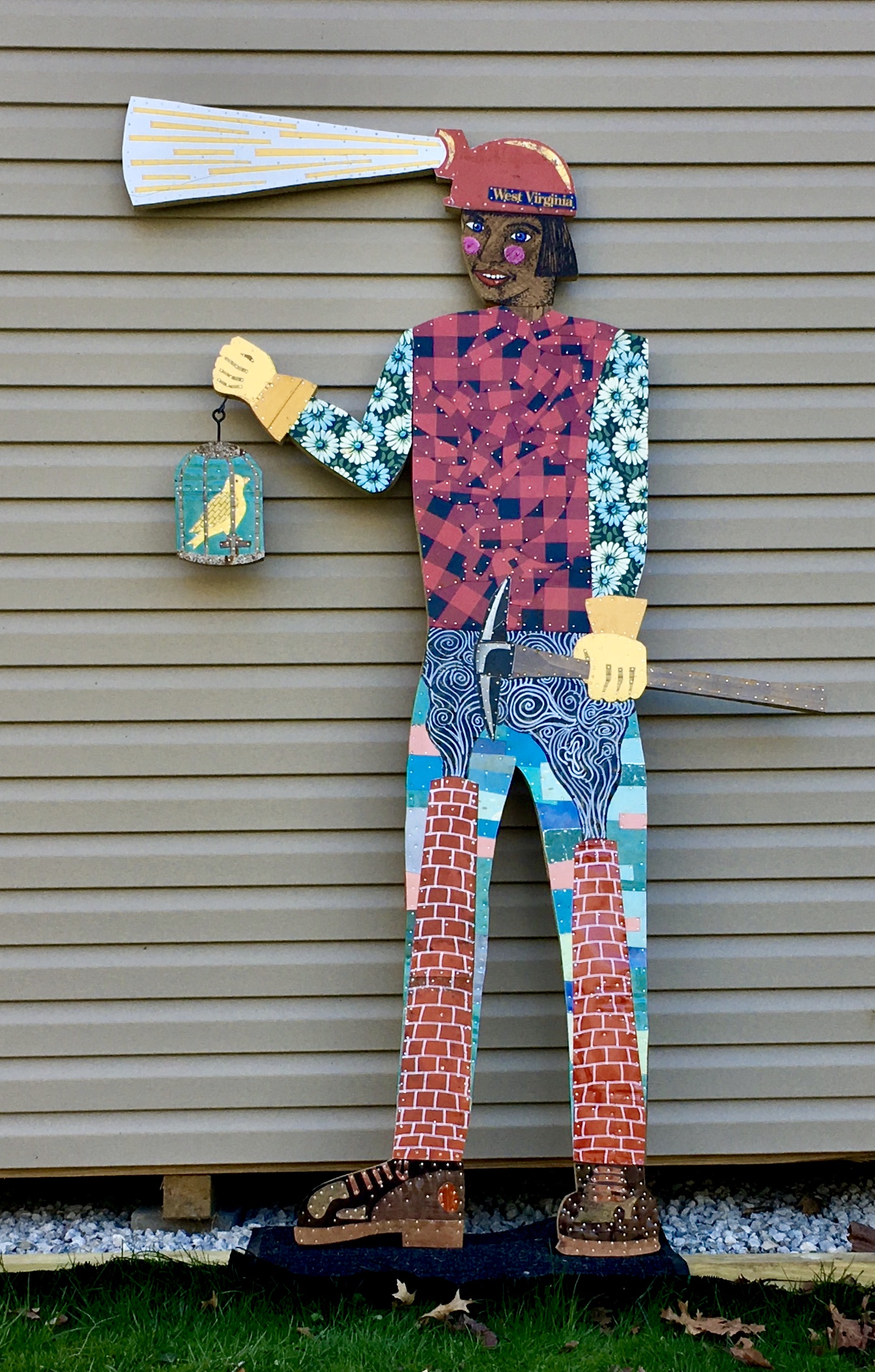

I’ve followed Wheeling mixed-media artist Robert Villamagna into his newly-constructed backyard shed. Maneuvering around some bikes, he unearths the head of a woman coal miner. She is rosy-cheeked and smiling beneath a bright red miner’s helmet labeled “West Virginia.” Her headlamp casts a two-foot-long pool of white-and-yellow light, all lithographic metal on wood. The head is just one part of full-length figure holding a canary cage, Villamagna explains.

“And it’s my best title I ever had, because I call her”—he waits a beat—‘Composition in She Miner.’ I’m so pumped about that!”

Villamagna’s enthusiasm is infectious. I can’t help but laugh and offer up a supportive “ba-dum ching!” At the same time, I’m marveling at the artistry of the piece. She Miner’s legs are billowing smokestacks, her vest a mess of red-and-black plaid, her sleeves an explosion of blue and white daisies. She radiates femininity and strength, a kind of Rosie the Riveter of coal mining.

When I set out to write an article about local artists repurposing Wheeling-made materials in creative ways, I was interested mainly in the material itself. What weird and wonderful things have people done with Wheeling tiles? LaBelle nails? Wheeling Corrugating tin? But after my conversations with two nationally respected local creatives, Villamagna and Glen Dale-based ceramic artist Betsy Cox, my focus shifted to locally-made meanings as much as materials.

Cox and Villamagna use local materials in their art both intentionally and as a matter of convenience. After all, one can hardly turn around in Wheeling without digging up some old glass bottles or finding somebody throwing out a perfectly good piece of Wheeling-made sheet metal. Cox’s distinctive use of LaBelle cut nails began when she found several old boxes cleaning out her parents’ basement in 1998. Afterward, she recalls, “I brought them down to my studio and thought, what am I going to do with them?”

Villamagna estimates 90% of the lithographic metal he repurposes in his artworks was manufactured between Pittsburgh and Cleveland. He has artist friends in the Pacific Northwest and San Francisco Bay Area who do similar work and they don’t find the materials he does in local flea markets. “It’s just natural this stuff comes up,” he shrugs.

Cox uses LaBelle nails exclusively in her nail pottery because she knows exactly how the metal will react with her clay body. She did “a lot of experimentation” to determine the precise temperature the metal needed to be to avoid cracking the clay. She also likes her nails with “a little bit of character” and considers it a plus that they came from the original machines that spit out nails that were slightly bent or the wrong size. Her insistence on LaBelle nails has led to minor sourcing challenges over the years, but her problems were solved when a local hardwood installer retired and advertised several fifty pound boxes on Craigslist.

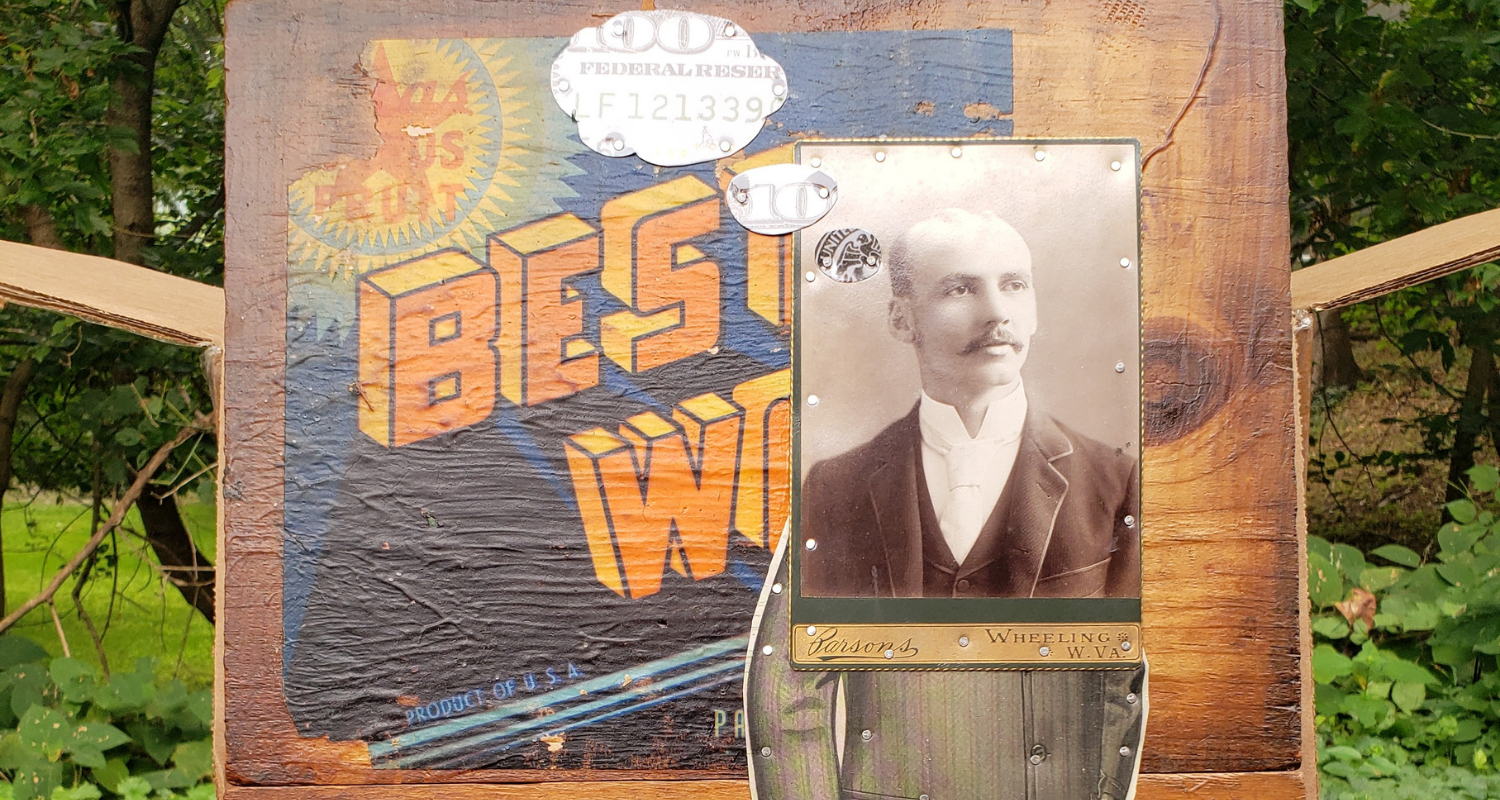

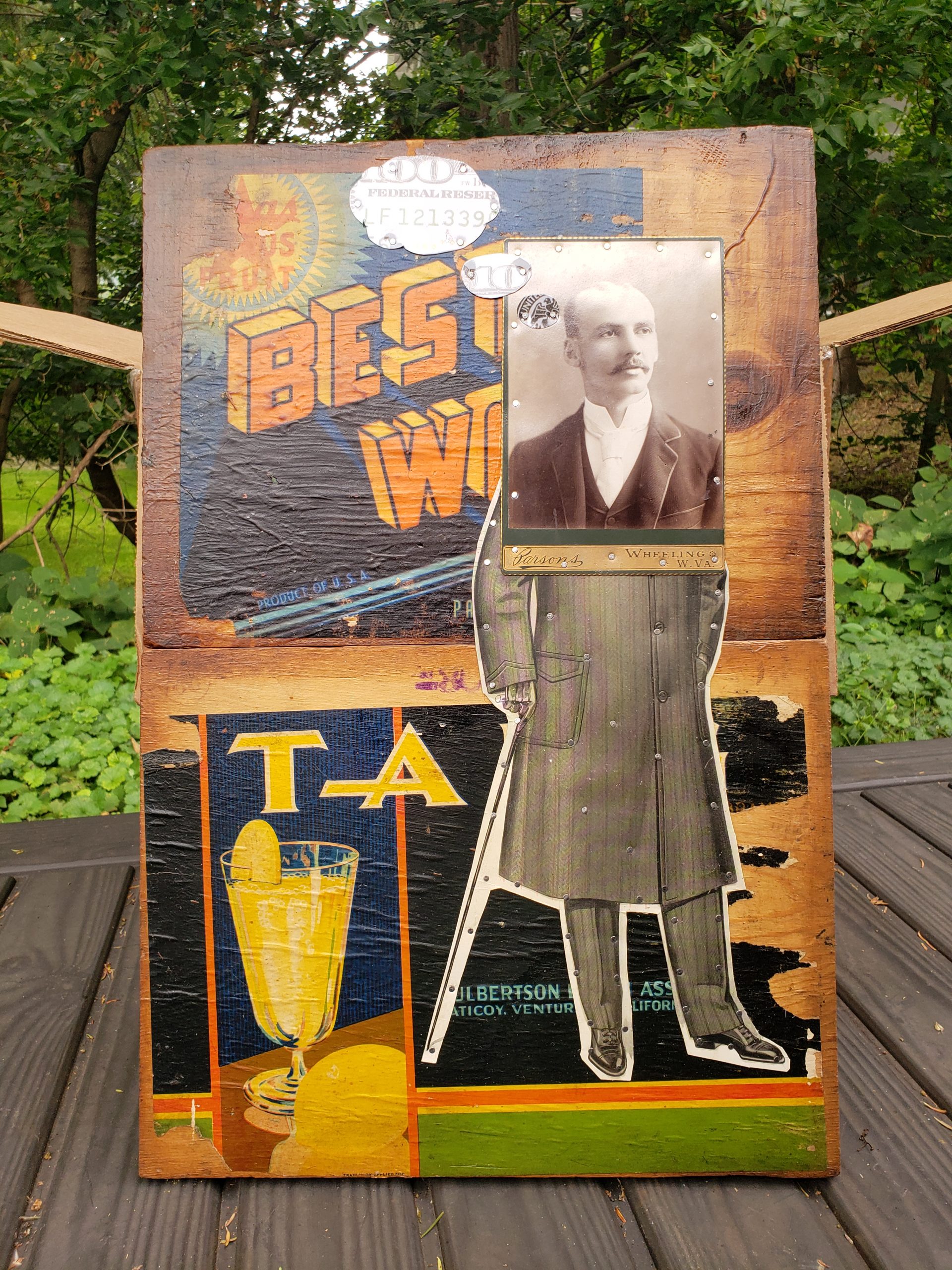

For his part, Villamagna “is drawn to [local] materials” but doesn’t use them exclusively. He estimates about half his works focus on industry and Wheeling Steel and Weirton Steel logos make frequent appearances in his collage work. He also stocks a file full of old Wheeling photos and used one in a piece as recently as last week. “I’m always hearing about ‘Old Wheeling Money,” he laughs, and so “Daydreaming About Old Wheeling Money” was born. He affixed the headshot of distinguished-looking Wheeling gentleman to a body from a 1912 suit and overcoat catalog and added one hundred dollar thought bubbles from a tin bank he had on hand. “I’m always poking fun,” he says.

Locally-made and inspired materials are an organic part of the creative process for both artists, their use inextricable from experiences of growing up, living, and working in the Ohio Valley. Villamagna quotes an artist friend from Oakland, California: “If I did one of my pieces about steel or coal industry…it would be so hokey! It wouldn’t work. That’s not where I come from.”

Cox would never use any nails but LaBelle nails because they would “have no connection, no meaning.” The nails she found in her parents’ basement were probably her father’s, who worked for the Benwood Plant of Wheeling Steel when LaBelle was a subsidiary. Her parents were also archaeology buffs and took her along on frequent trips to the Grave Creek Mound Complex in Moundsville. As a young girl, Cox could always be found “pounding nails” or “collecting rocks” and to this day she’s still “down in the creek about every day picking up sticks and stones.”

From her “crow shrines” to her succulent-inspired pottery, Cox’s deep-seated love of nature and found objects is evident across all her works. She often uses LaBelle nails to represent the prickly spines of cacti, but she uses them in more abstract ways as well. Sometimes she’ll just look at a piece after it’s finished and think “that needs a nail.”

Villamagna worked for thirteen years in the Weirton Steel plant, eleven years longer than he intended. He was miserable and it showed. “One day,” he recalls, “my boss said “‘Hey Villamagna, what’s the matter? You look a little down’…and I said, ‘well I guess I’m just really unhappy here.’ And he said, ‘Well if you could do anything right now instead of this what would it be doing?’ ‘You know,’ I said, ‘making art.’ And he said, “Well why don’t you make art about this place? You’re living in the belly of a dinosaur. One of these days you’re going to be able to tell your grandchildren about this place.” He balked at the time, but Villamagna says he’s separated from the experience enough now to use it in his art. He knows he romanticizes it, too – his wife, Chris, tells him as much.

Musing on steel industry nostalgia, Villamagna reveals that an original artwork may still lie in the stockhouse below the Weirton Steel blast furnaces. In 1983, he spray-painted enormous caricatures of his coworkers on a brick wall they dubbed the “Hall of Laborers.” The last time he saw it was in 1986. Iron ore dust had covered it so completely, he says, that “all you could see was the top of their helmets and maybe just a little bit of their eyes.” Just one more locally-made treasure, waiting to be found again.