Over the years, Wheeling has been home to numerous award-winning people in various fields—from singers to actors to artists and more. However, not many Wheeling residents know that Warwood boasts two internationally decorated floriculturists in its history—Dr. William and Elizabeth Webb.

The Doctor Sets Up Shop

William Webb, originally from Ohio, graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Baltimore, Maryland in 1904 and married Emma Lisle Brock shortly thereafter. The growing Webb family moved to Warwood in 1909, eventually building a home at 1705 Warwood Avenue in 1917. It’s not clear when or where Dr. Webb’s interest in floriculture—the cultivation of flowers—began, but one of the first mentions of his flower hobby appeared in the Wheeling Intelligencer in 1929, though it is clear it started earlier.

The house simultaneously served as a home for their family and a doctor’s office. The right side of the house included three rooms that served as an examination room, a medicine room, and a waiting room. As was typical at the time, Dr. Webb would make home visits and treat patients at Wheeling Hospital, in addition to appointments at his home office.1

Dr. Webb volunteered his services to his community, using both his medical and gardening skills. During World Wars I and II, he served as a member of the U.S. Volunteer Medical Service Corps for the Ohio County Draft Board and also volunteered as the Warwood High School Physician.2 Due to his success at flower shows, Dr. Webb was asked to help arrange the new shrubs and trees in Warwood Park in 1929.3

Unfortunately, Dr. Webb’s wife, Emma, died in 1935, after three decades of marriage. He remarried two years later, in 1937, to Elizabeth Louise Ahart, a registered nurse at Wheeling Hospital. 4 William and Elizabeth shared a love of floriculture and began to work on their flower hobby together.

Success Blossoms

Given her nursing and laboratory background, Elizabeth began to work with Dr. Webb in his home office, coordinating the invoices and performing lab work. Elizabeth was actually responsible for creating an in-house lab. Previously, Dr. Webb would have to send lab samples to an outside lab to be tested; the change allowed the Webbs to save money and time.5

As they sustained their medical practice, they continued to cultivate large flower gardens in the backyard of their Warwood home. The gardens were often visited by patients waiting for their appointment. The Webbs enjoyed experimenting by trying to create their own hybrids, always in search of a better flower. Elizabeth transferred her medical skills to the garden by x-raying seeds in an attempt to change their genetic composition for a new hybrid. In 1946, they bought a farm north of Warwood to expand their flower gardens, known for years afterward as “Webb Farm.” 6

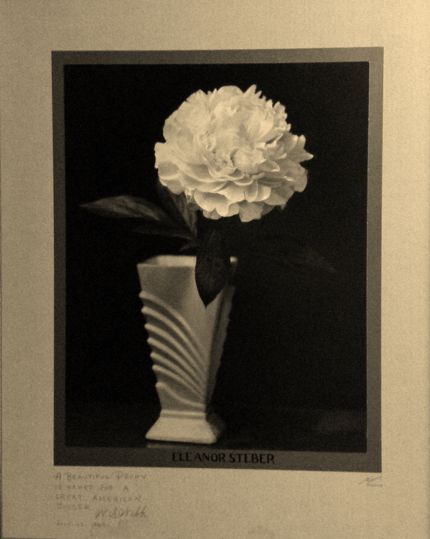

The Webbs grew all sorts of flowers including roses, lilacs, irises and peonies, but they were most well known for their gladioli. Dr. Webb was a leading member of the West Virginia Gladiolus Society and the Webbs often hosted picnics for other members at their farm. Other friends and admirers would continue to visit their farm and gardens, even though they were several miles out of town. The Webbs even named one of their peony varieties after their friend and famous Wheeling opera singer, Eleanor Steber.7

In 1950, one of the Webbs’ gladioli, “White Symphony,” won the Grand Champion prize at the West Virginia Gladiolus Society show, held at the Oglebay Pine Room. The next year, it won the prize again.8 After the two years of success with “White Symphony,” the Webbs struck a deal with Alfred Moses, a commercial grower, and used the extra money to pay off the debt on their farm.

Webbs’ Legacy Continues to Grow

Only a few short years after “White Symphony” won Grand Champion, Dr. William Webb died on April 11, 1952 at Wheeling Hospital.9 According to the Webb family, an impressive 1,700 people paid their respects or attended his funeral.10

Even after William’s death, Elizabeth continued their shared floriculture hobby. In 1954, she even donated a White Symphony bouquet to be given to the renowned opera singer, Helen Traubel, after she performed at the Oglebay Park Amphitheater.11

While the Webb farm has been sold out of the family and few are left to remember the acres and acres of flower gardens, William and Elizabeth’s son, William Webb Jr., continues to advocate for their memory. In 2021, both Dr. William and Elizabeth Webb were posthumously inducted into the International Gladiolus Hall of Fame, along with their prize-winning flower, “White Symphony.”12

Special thanks to William S. Webb, Jr. for sharing his parents’ story and love for flowers.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 William S. Webb, Jr., and Judith Webb Greenan, “The Family of Dr. William Stephen Webb,” unpublished family history.

2 “Dr. William Stephen Webb Obituary,” Wheeling Intelligencer, April 12, 1952.; Webb, Jr., and Greenan, “The Family of Dr. William Stephen Webb.”

3 “Dr. Webb to Aid in Work,” Wheeling Intelligencer, June 14, 1929.

4 Webb, Jr., and Greenan, “The Family of Dr. William Stephen Webb.”; “Dr. Webb Weds Miss Ahart,” Wheeling Intelligencer, April 29, 1937.

5 Webb, Jr., and Greenan, “The Family of Dr. William Stephen Webb.”

6 William Stephen Webb, Jr., “Nomination for the International Gladiolus Hall of Fame,” 2020.

7 Webb, Jr., and Greenan, “The Family of Dr. William Stephen Webb.”; William Stephen Webb, Jr., “Nomination for the International Gladiolus Hall of Fame,” 2020.

8 Wheeling Intelligencer, August 7, 1950, p. 8.

9 “Dr. William Stephen Webb Obituary,” Wheeling Intelligencer, April 12, 1952.

10 Webb, Jr., and Greenan, “The Family of Dr. William Stephen Webb.”

11 William Stephen Webb, Jr., “Nomination for the International Gladiolus Hall of Fame,” 2020.

12 “International Gladiolus Hall of Fame Inductions,” International Gladiolus Hall of Fame, 2021, accessed June 30, 2021, http://www.gladworld.org/Hall%20of%20Fame%20Inductions%20%20all%20to%202021.pdf