“This ceremony, it wasn’t born from complaints. There weren’t protests demanding this happened. It’s happening right now because it’s the right thing to do and it’s long overdue. These events make sure we understand history from both sides.” – Ron Scott

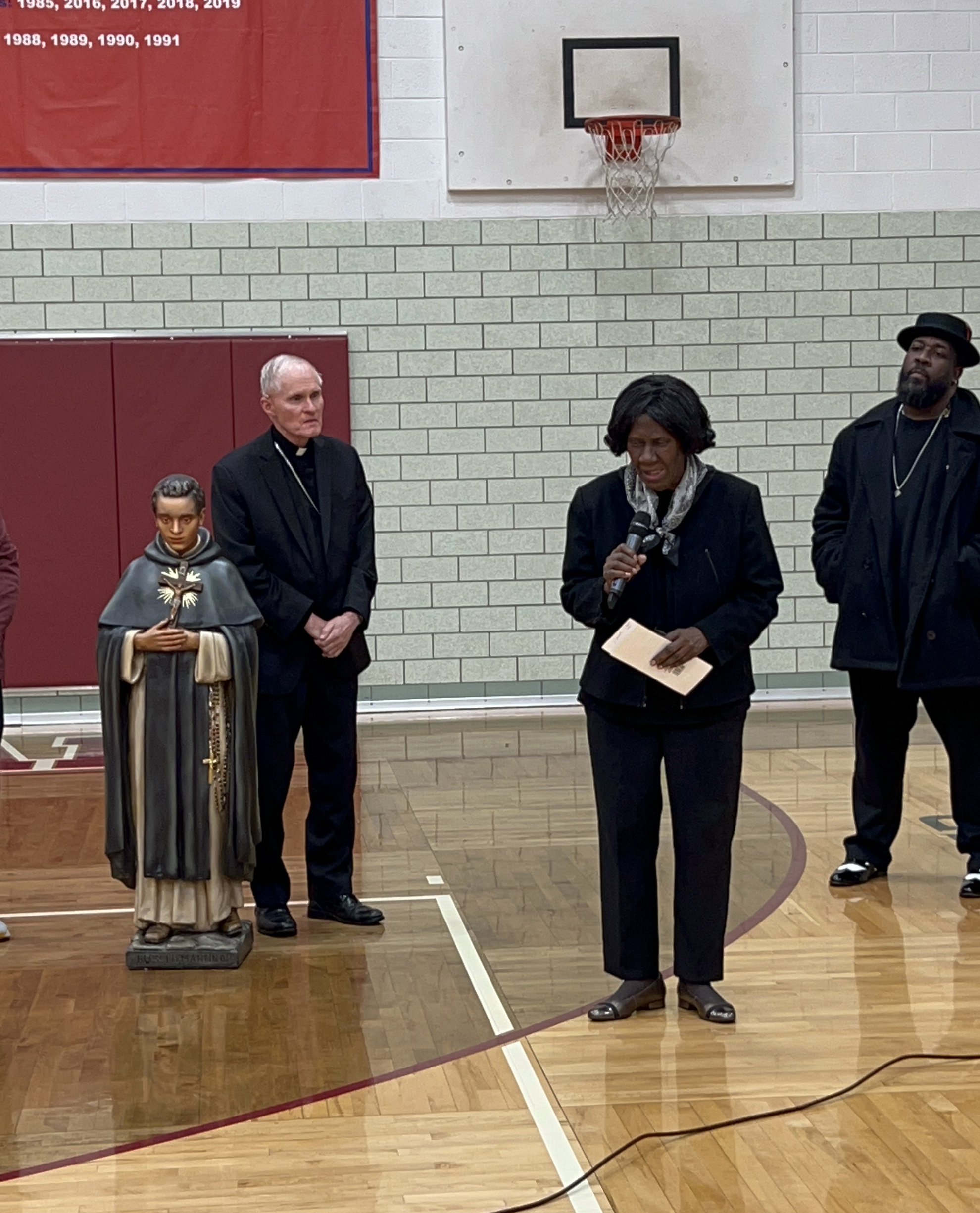

It’s not every day that a replica of a lost statue is blessed during a high school basketball game. Which is just as well, because it turns out that January 24, 2023 certainly was not like every other day. It was the day that a gymnasium became far more than a gymnasium. It was the day that the past burst forward into the present, where an almost-forgotten school regained its name, where the students of the past were honored. It was the day St. Martin de Porres returned to Wheeling.

A Blessing During a Basketball Game

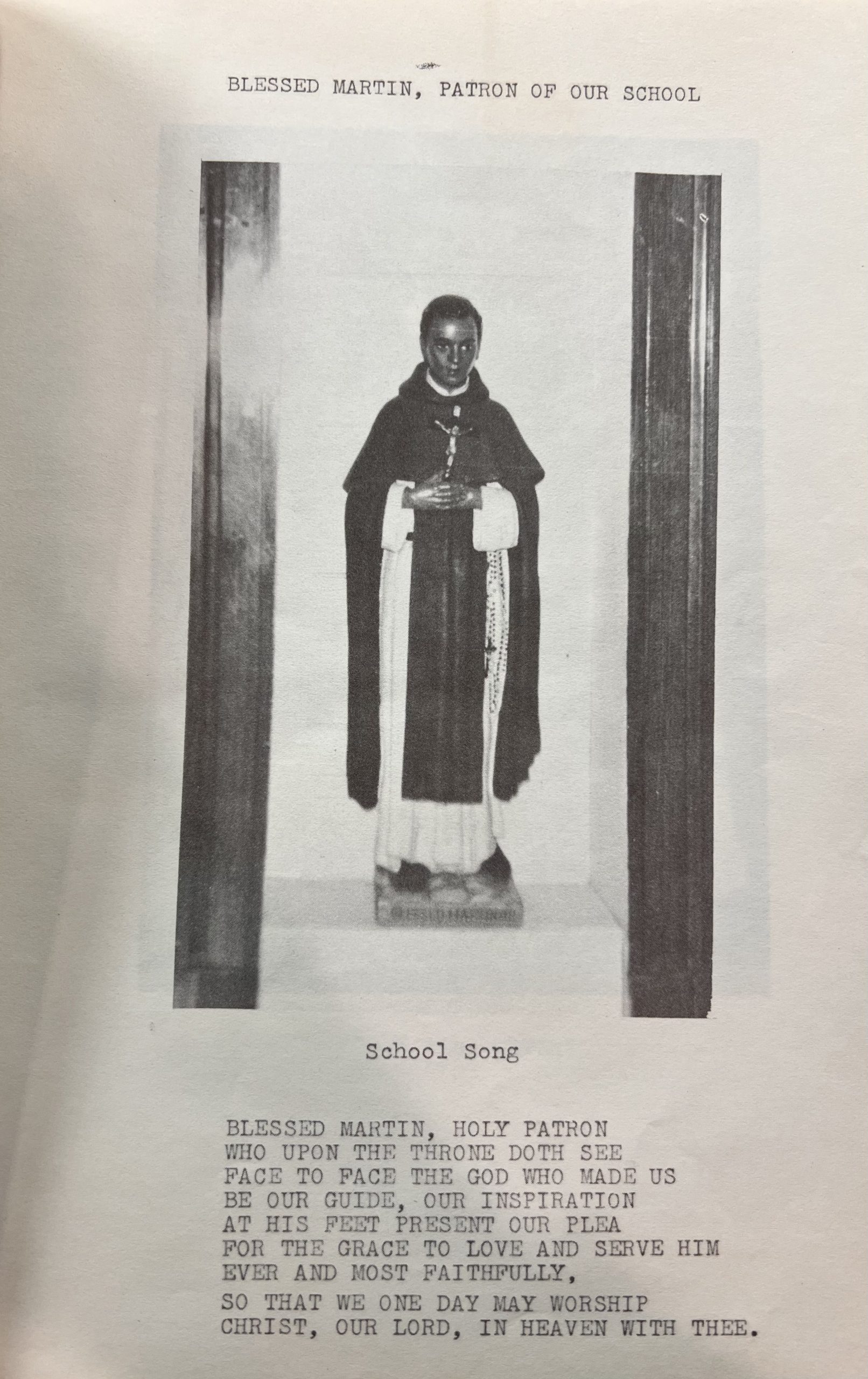

St. Martin de Porres represents overcoming stereotypes and working towards racial equality and harmony. The ceremony on January 24 would have made St. Martin quite proud.

The ceremony was kicked off with a short film made by students at Wheeling Central Catholic High School, the subject of which was the story of Harry H. Jones and Wheeling’s Twentieth Man. (Side note: the film won first place in the state at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday Committee Essay, Film, and Song Contest!)

Following this was a moving speech from Tim Bishop, Director of Marketing and Communications for the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston (more on him later).

Mr. Bishop then passed the microphone to Ruth Stinson, a former student of the Blessed Martin school in Wheeling. Blessed Martin School was established in 1942 as a segregated Catholic school for boys and girls. Stinson regaled the audience with remembrances of her time spent at Blessed Martin, stating, “You’re standing on history, and we that have been here carry it in our hearts.” Mrs. Stinson then called forth on three fellow former students to stand up and be recognized.

Following Ruth Stinson, Director of Cultural Diversity at the YWCA, Ron Scott, Jr. then took the floor, saying,“This ceremony gives roots and a home to everyone who talked about Blessed Martin. It’s acknowledging that we see you, we’ve always seen you, and you’re a part of us. This is one of those events that we’ve been able to witness how Black history turns into our history, which is American history. It connects and affects each and every one of us.”

This was followed by a few words from Bishop Brennan whereafter he formally blessed the statue of St. Martin de Porres. Just when you thought the ceremony was over, a former student, Mrs. Alice Walker, stood in the stands and sang the Blessed Martin School fight song to the entire gymnasium. An absolutely perfect ending to a ceremony designated to pay homage to the school and students who once inhabited the space.

St. Martin de Porres is on duty once again, waiting to greet students and remind them of the history and significance of the ground where he stands.

This celebration of St. Martin de Porres and Wheeling’s Blessed Martin School has been a long time coming.

Read on to learn the remarkable story of the Blessed Martin School, the religious and cultural impacts it had on the Wheeling community, and how the paths of a bishop, librarian, and archivist crossed in order to bring a statue back to the ground where it once stood over 80 years ago. It’s not the original statue, by the way. The original statue is as lost to time as the building itself. So how did the ceremony happen? Let’s dig in!

It Started with Research: The Gift That Keeps on Giving

In 2020, Sean Duffy, Programming Director and Local History Specialist at the Ohio County Public Library, published a wonderful article about the St. Martin School on Archiving Wheeling, which you can check out here! While writing this article, he collaborated with Jon-Erik Gilot, Archivist for Wheeling-Diocese, to get additional information on the school’s history. This collaboration is what set the wheels in motion.

A year later, in 2021, Bishop Brennan expressed a desire to see the diocese do more to recognize the Black history of the Wheeling-Charleston Diocese, which lead Gilot to dive once more into the history of Blessed Martin.

“I was familiar that the school, Blessed Martin, was here during the era of segregation; I have a few yearbooks, but we don’t have anything visceral,” Gilot tells me. It seemed that progress was at a standstill until another twist of fate set the wheels in motion once again.

“In 2022, a friend of mine was at the Diocese of Pittsburgh; they’re going through a restructuring right now, and have a warehouse of things they are taking out of churches,” he continues. “He showed me a picture of the warehouse, and that’s where I saw a picture of the statue of Blessed Martin. I thought it looked familiar, and when I checked the Blessed Martin yearbook, I saw they were identical.”

The statue was purchased from the Pittsburgh Diocese, transported to Judy Dotzel of Trinity Artisans for expert restoration, and finally came home to Wheeling.

So how did Ron Scott Jr., Tim Bishop, and Ruth Stinson enter the picture? Great question, the answer is coming up.

A Real-Life Domino Effect

For those who don’t know, the Ohio County Public Library (OCPL) has a robust catalog of programming, ranging on a variety of topics from Toddler Time and STEAM classes for kids, Trivia Night, Book Club, D&D Night, and Genealogy Workshops for teens and adults. The library also focuses on BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) displays, workshops, and panels. It is this type of programming that enticed Ron Scott, Jr., Cultural Diversity and Community Outreach Director for the Wheeling YWCA, to enter the story.

Ron collaborates regularly with OCPL, and when he heard about the dedication and blessing of the St. Martin de Porres statue, he knew he could contribute to the event.

“The library does the kind of programming that should be done,” Scott says. “We just did a panel about the Bobby Wade incident [a 1971 tragedy involving police raids and an unexplained suicide in Wheeling]. Growing up that was a story that got told, but there wasn’t a lot of connection to it, even though it didn’t happen that long ago. At this event, the people on the panel were there, and they gave a factual, first-hand account of what happened. And it’s important for the community to hear that.”

Being a champion and facilitator of community programs, Ron joined in on the unveiling mission for St. Martin. In doing so, Tim Bishop was introduced to a woman Ron knew, a woman who would make the story of the Blessed Martin School real to him in a way that documents and yearbooks could not: Mrs. Ruth Stinson.

“We had a couple meetings, and at the last one Ron mentioned that he knew Ruth Stinson, a former student of Blessed Martin,” Tim Bishop informs me. “He put me in touch with her, and over the course of several beautiful conversations, she told me her story.”

Blessed Martin, The School that Almost Wasn’t

Let’s go back. Way back.

The year is 1942, and Black members of the Catholic Church want the same educational opportunities for their children that white kids have, namely: a Catholic education. Due to segregation laws at the time, Black children could not just sign up and go to the local Catholic school, the law required that they have their own, specifically for black students.

The St. Joseph Cathedral and the Sisters of St. Joseph were determined to open the Blessed Martin School, but this turned out to be no mean feat. The first time the school tried to open its doors, enrollment was too low; the second time around, it is speculated that fear of persecution, harassment, and abuse was what kept the students away. The Bishop at the time, Bishop Swint, decided that the school was simply not meant to be. Bishop Swint did not anticipate the grit and determination he would soon be met with.

After the second closing of the school, a group of six women and one man from the local Catholic African American community requested a meeting with Bishop Swint. The Bishop’s decision was no match for the seven Black Catholics; their emotional plea moved the Bishop and he agreed to open the school on one condition: the elders needed to deliver a few students for each grade (1-8) the next morning. To the surprise of no one, they did it.

And so it was that through the conviction and persistence of a small community that St. Martin de Porres Catholic School was finally able to open its doors and give local Black students the opportunity to attend a Catholic school. Despite the success of the school finally opening, there was still a lot of backlash from the community.

“Ruth told me how Monsignor Yahn used to protect the kids walking into school from harassment. How young boys would be harassed by the police, be arrested and taken to jail, and Monsignor Yahn would get them out,” Bishop recounts. “The audacity to harass a child who just wants an education is a whole different level of evil. As a father, that shakes me more than anything else.”

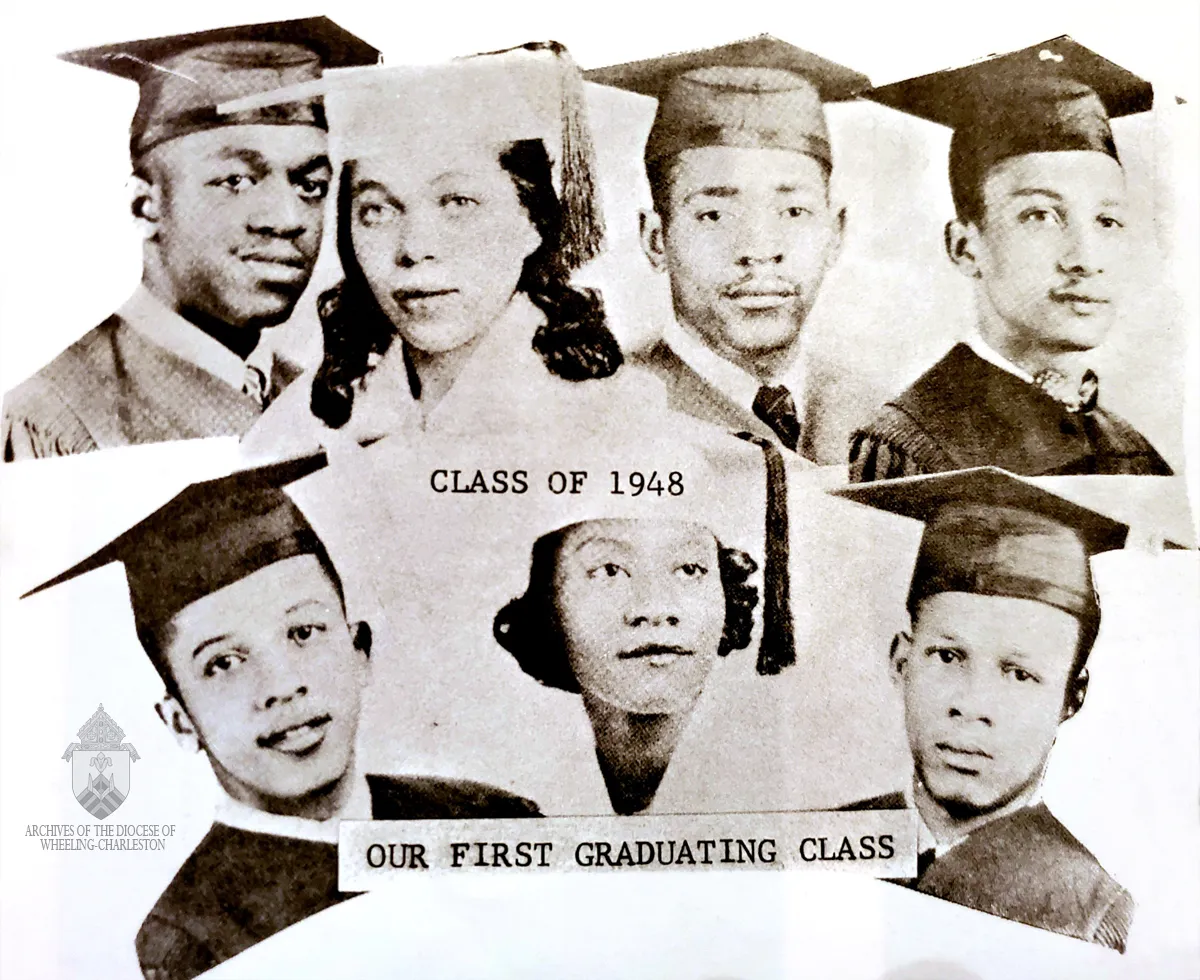

The school’s motto was: “Climb through the rocks – be rugged.” And rugged it was. In the face of profiling, adversity, and racism, the Blessed Martin’s curriculum earned a Class-A rating from the State Board of Education in Charleston in 1948. That same year, ten full scholarships to formerly all white Catholic universities were awarded nationwide to African American graduates of Catholic high schools. Three of the ten went to Wheeling’s Blessed Martin honor students.

The school grew in popularity year over year, eventually adding high school grades and averaging about 125 students by the time it closed its doors in 1955. Each day, the statue of St. Martin de Porres, a gift from the Dominican Fathers of NYC, was there to welcome students as they entered through the doors.

It Really Does Take a Village

A school, a diocese, a library, and a community organizer came together to make this event possible. An event that not only honored Wheeling’s Black community and history, but highlighted the Black experience in Wheeling during times of segregation. White and Black students and community leaders worked together to bring the reality of Black history to life, working against historical white-washing.

“The sisters were doing the real work teaching, Monsignor Yahn was doing the real work in looking after the school and the children, the parents did the work of making sure their child got a Catholic education, and the students did the work of showing up every day,” Bishop says.

“The work was much harder for the African American community to attend the school than it was for the bishop to create the school. This [statue] honors the foundation that the congregation of St. Joseph’s built; it honors the young men and women who attended the school, more so than the diocese who created it.”

Our community worked together to pay homage to an institution of the past that shaped the lives of fellow community members, while addressing segregation, a subject that makes people uncomfortable. Because they know that’s the only way to drive out the darkness of the past: to shine a light on it.

If that doesn’t make you swell with pride for your city, I honestly don’t know what will.

• Haley Steed has lived in Wheeling for the past 9 years. Before moving to Wheeling, she lived in Columbus, OH where she graduated with a BA in Comparative Cultural Studies from Ohio State University. Haley also earned an MS in Marketing and Communications from Franklin University. She has held multiple marketing positions for 10+ years, with experience in PR/media relations, internal communications, marketing campaign strategy + execution, SEO, branding, content creation, digital analytics, and graphic design. Haley currently serves as an AmeriCorp member at Wheeling Heritage. Haley has one human named Vida, two cats named Hank and Squigs McAllister, and is currently manifesting that her one-day husband’s name will be Jeffrey Goldblum.