West Virginia Day is almost upon us and it is the 158th anniversary of West Virginia officially becoming a state. Approximately two years after deciding not to secede during the Civil War, West Virginia became the 35th state on June 20, 1863.1 However, do you know about the previous times that the area of West Virginia almost became a different state?

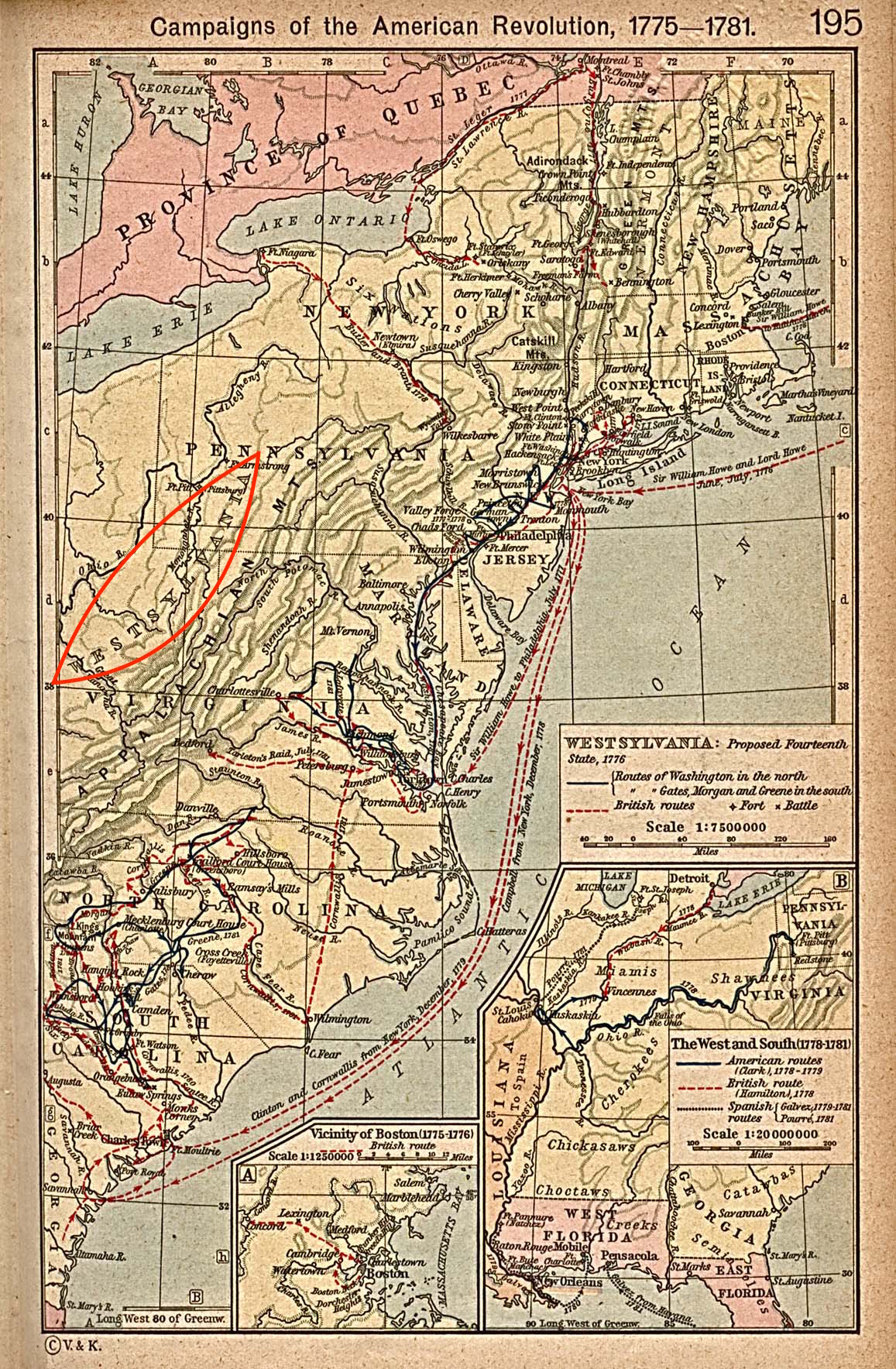

There were numerous discussions of the western Virginia region separating from the eastern region throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, from informal tavern chatter to formal legal conversations. Most were no more than pipe dreams, but a few got so far as to have names for the new area chosen—like Vandalia and Westsylvania.

Vandalia

During the late 18th century, the land west of the Appalachian Mountains was still largely undeveloped by Europeans. While this was in part due to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited colonial settlement past the Appalachian Mountain range, many settlers ignored the decree. In 1768, the Fort Stanwix Treaty moved the boundary line further west and land speculators became very interested in the western Virginia region.2

Land speculators are people or groups of people who buy up undeveloped land as an investment strategy—in this case, colonial land speculators were banking on settlers moving out west, establishing communities, and buying property. A group of American and English land speculators formed the Grand Ohio Company, eventually called the Walpole Company, in 1769 and began to lobby for a new 14th colony, Vandalia, in the region of modern-day West Virginia and part of Kentucky.3

The name was chosen to honor and curry favor with the British Royal Family, as Queen Charlotte was supposedly descended from the Germanic Vandal tribe.4 The company was backed by numerous prominent men, such as Thomas Walpole, William Franklin (Benjamin Franklin’s son), and the prominent Quaker Wharton family of Philadelphia.5

There were numerous challenges and hurdles to successfully creating Vandalia including opposition by the colony of Virginia and Lord Hillsborough back in Great Britain.6 The Vandalia Colony got so far as to have a charter drafted, but with the onset of the American Revolution, the authority of Great Britain to create a new colony was dashed.7

Westsylvania

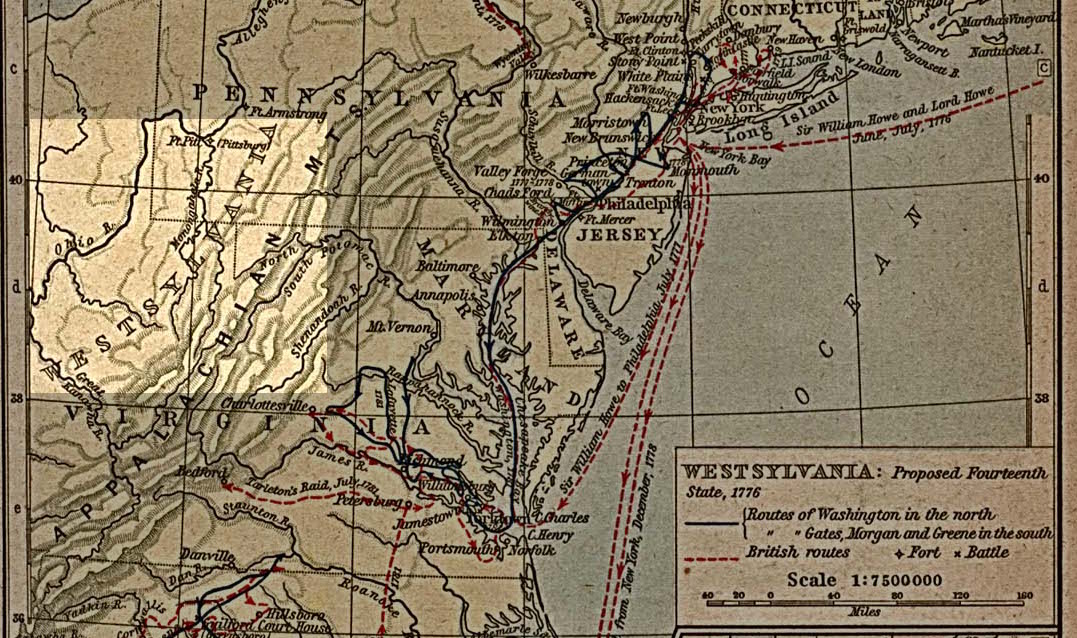

Even though Vandalia failed with the onset of conflict between the colonies and Great Britain, the concept of a separate western Virginia colony did not disappear completely. Years earlier, in the early 1770s, Virginia and Pennsylvania began squabbling over who had jurisdiction in the region west of the Alleghenies—what is now mostly western Pennsylvania. According to Alan Gutchess, the Director of the Fort Pitt Museum, “the documents that established Pennsylvania and Virginia were vague enough to be interpreted as placing what is now a large part of Western Pennsylvania in both colonies.”8 Much of the land wasn’t officially surveyed and boundaries were far from clear.

While the dispute wasn’t exactly new, in 1773, Virginia’s Royal Governor, Lord Dunmore, visited Pittsburgh and began implementing actions to officially take over the contended area. In early 1774, Virginia organized a local militia, replaced Pennsylvanian courts with Virginian courts, and occupied and renamed Fort Pitt to Fort Dunmore.9

Both Virginia and Pennsylvania had their central governments back east, and the residents of the disputed western region grew tired of all the intervention by governments hundreds of miles away. A group of residents came together and sent a petition to the Continental Congress in 1776 arguing for a “separate, distinct, and independent Province & Government of…Westsylvania.”10 If the colonists won their independence from Great Britain, it would become the 14th state. However, the Continental Congress, apparently with other more pressing matters at hand, ignored the petition.11 Subsequently, the Pennsylvania General Assembly made it treasonous, and therefore illegal, to discuss the development of a new state out of western Pennsylvania.12

The proposed Westsylvania would have included most of what is currently West Virginia (with the exception of the eastern panhandle), southwest Pennsylvania, and small chunks of Kentucky and Maryland. Even though Westsylvania was never created, throughout the American Revolution, Pennsylvania kept pushing for the return of some of the disputed western territory. Finally, between 1779 and 1780, an agreement was reached and Virginia returned a lot of the area to Pennsylvania.13 The boundaries between Virginia and Pennsylvania became clearer, but it would be another 83 years before the new state of West Virginia was formed.

The Legacy of Vandalia and Westsylvania

Even though Vandalia and Westsylvania didn’t make the cut to become West Virginia, their names still persist in certain places and events throughout the region. The Westsylvania Jazz and Blues Festival in Indiana, Pennsylvania and the Vandalia Gathering in Charleston, West Virginia are held every summer. There are even several small cities in the Midwest named Vandalia, although it is disputed whether the proposed 14th colony was actually their namesake. One of them, Vandalia, Illinois, is even host to one of the Madonna of the Trail statues—sharing another historical legacy with Wheeling.

The failures of campaigns for Vandalia and Westsylvania paved the way for West Virginia to become the only state born out of the Civil War. Just think—instead of celebrating being citizens of WV this West Virginia Day, we could be referring to ourselves as “Westsylvanians” or “Vandalians,” which don’t exactly roll off the tongue.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “West Virginia Statehood,” West Virginia Archives & History, accessed May 17, 2021, http://www.wvculture.org/history/archives/statehoo.html.

2 “1768 Boundary Line Treaty of Fort Stanwix,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, May 11, 2020, accessed June 8, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/fost/learn/historyculture/1768-boundary-line-treaty.htm.

3 Thomas White, Forgotten Tales of Pittsburgh, Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2010.

4 Lori Henshey, “Vandalia Colony,” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia, July 13, 2020, accessed April 20, 2021, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/857.

5 “Proceedings of the Virginia Committee of Correspondence,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 12, no. 2 (October 1904): 157-169.

6 “Proceedings of the Virginia Committee of Correspondence,” 160.

7 Chad J. Wozniak, “The New Western Colony Schemes: A Preview of the United States Territorial System,” Indiana Magazine of History 68, no. 4 (December 1972): 299.

8 Alan Gutchess, “Pittsburgh, Virginia?,” Western Pennsylvania History, (Summer 2014): 6.

9 Ibid.

10 G.L. Cranmer, History of the Upper Ohio Valley: Vol. 1, (Madison, WI: Brant & Fuller, 1891), 62-63.

11 Brian O’Neill, “The great state of Westsylvania? It never came to be,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 12, 2018, accessed April 20, 2021, https://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/columnists/2018/08/12/Brian-O-Neill-The-great-state-of-Westsylvania-It-never-came-to-be/stories/201808130005.

12 O’Neill, “The great state of Westsylvania? It never came to be.”; White, Forgotten Tales of Pittsburgh.

13 Gutchess, 7.